How One Primary Gave Democrats Affordability

Zohran Mamdani’s upset win did not change the map, it changed the script that Democrats now run on.

Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral primary was supposed to matter only inside New York City politics. Yet if you look at how members of Congress talk about the economy, that one race shows up like an earthquake.

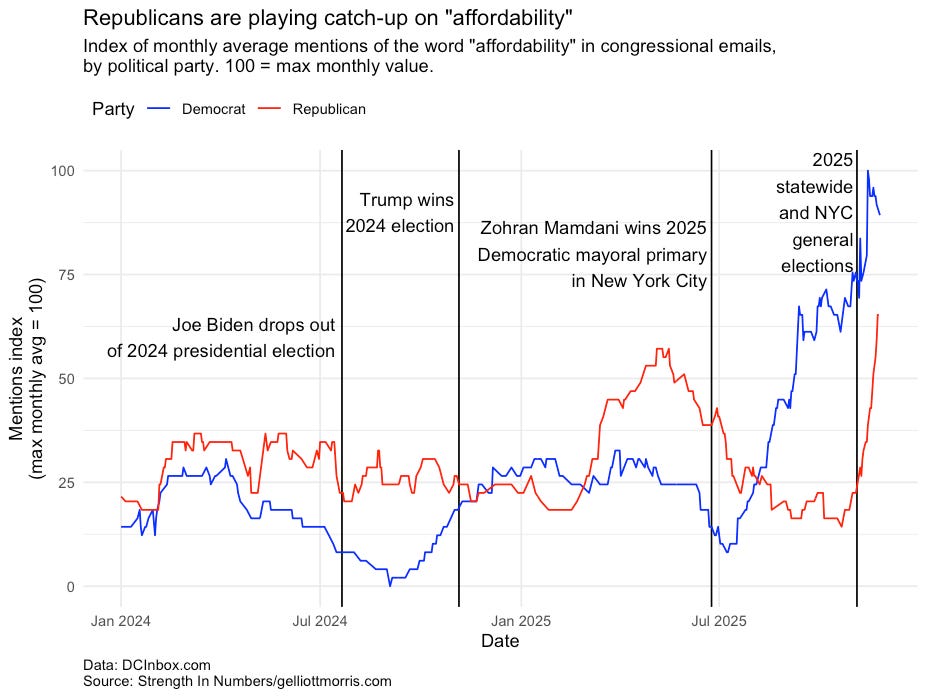

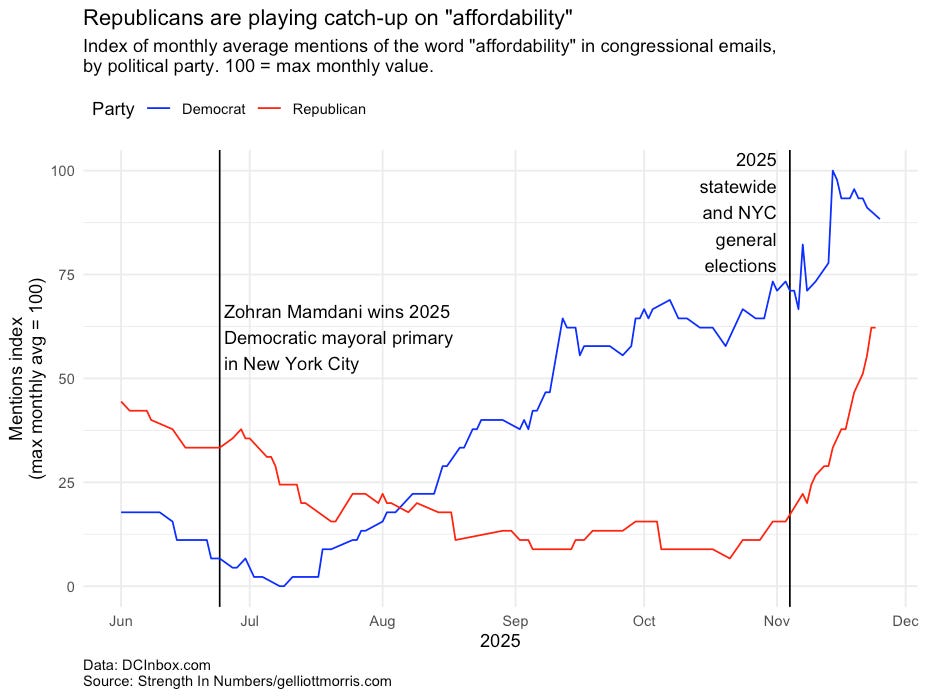

G. Elliott Morris’s innovative research tracks how often Democrats and Republicans use the word “affordability” in constituent emails. Through most of 2024, both parties sit in the middle of the chart, with Republicans actually using the term slightly more. Joe Biden drops out. Donald Trump wins the presidency. The lines barely move. Democratic mentions drift toward zero by mid-2024 and only slowly recover. As Morris writes:

Mamdani’s primary win in June 2025 is where you see the real inflection for affordability. Democratic mentions jump and never return to their earlier baseline. It’s the moment when affordability goes from being a niche progressive word on email newsletters to a party-wide message.

Most arguments about inflation and the cost of living stay at the level of macroeconomics. These charts point to something more political: they show how a single primary in New York reset what Democrats from safe blue districts to front-liners think it’s safe — and necessary — to say and frame about the economy.

The claim here isn’t that progressive candidates in big cities don’t care about persuading swing-seat voters. It’s that party realignments rarely start in swing seats at all. The anti-slavery movement of the 1840s and ’50s, the industrial-union Democrats of the New Deal, the civil-rights coalition of the 1950s and ’60s, and the conservative movement of the 1970s and ’80s all followed the same script: first consolidate power on home field, then pull a shapeless political center in their direction.

Safe Democratic seats in large, diverse metros play a crucial role today. They’re where the party’s core voters are densest, where campaign and policy ideas can be tried at full strength, and where future, entrepreneurial staff and messengers get trained. When a candidate wins there with a different story about the economy, it doesn’t stay local. It becomes a template for every Democrat looking for a way to answer the same voter anxiety.

Some pundits are now borrowing a term from sports analytics. “Wins above replacement” in baseball measures how many extra games a player is worth compared with a generic substitute. This version asks how much better a candidate does than a “generic Democrat” once you control for partisanship, incumbency, and money. Despite some reservations on the actual data and math here, it’s a somewhat sensible way to think about nominees in swing districts.

But it misses what races like Mamdani’s actually do. They are less another brick in the existing structure and more a new blueprint for how the party’s house can be built. A single safe-seat member does not add square footage to the Democratic majority, but they can alter the design: which rooms get the most space, which issues sit at the center rather than the edges. Over time, even cautious incumbents begin renovating their own plans to match that new layout, including the language they use and the priorities they emphasize.

The Green New Deal is an obvious, more recent precedent. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez didn’t flip a Republican seat in 2018. She won a safe Democratic district. Yet her victory, and a small cluster of similar ones, helped push climate to the center of the party’s agenda and shape the eventual contours of the Inflation Reduction Act. Moderates like Mikie Sherrill and Abigail Spanberger did not run on the Green New Deal. But they ended up voting for a climate-heavy industrial policy their party probably wouldn’t have produced without pressure from its safest members aligned with a social movement organizing a constituency of voters.

Mamdani’s primary is the affordability version of that story. On paper, it is another Democratic win in a city Democrats already run. In practice, it did something the party had struggled to do for three years: it distilled the inflation debate into a frame Democrats could actually fight on. MWithin months, that vocabulary shows up not just in left-aligned newsletters but in the emails of swing-district Democrats whose voters look pretty different from Queens, because they are hearing the same complaints about rent, child care, and groceries and because Mamdani has shown that this is a way to engage the argument.

That’s the strategic case for paying attention to deep-blue primaries. The national party and its major donors will always saturate the marquee swing races; an extra dollar there mostly buys another ad buy or poll: “Republicans bad, Democrats good.” In safe seats, that same marginal dollar can change who holds the office — and with them, the assumptions that shape how Democrats describe the economy and what they demand when they negotiate with Republicans.

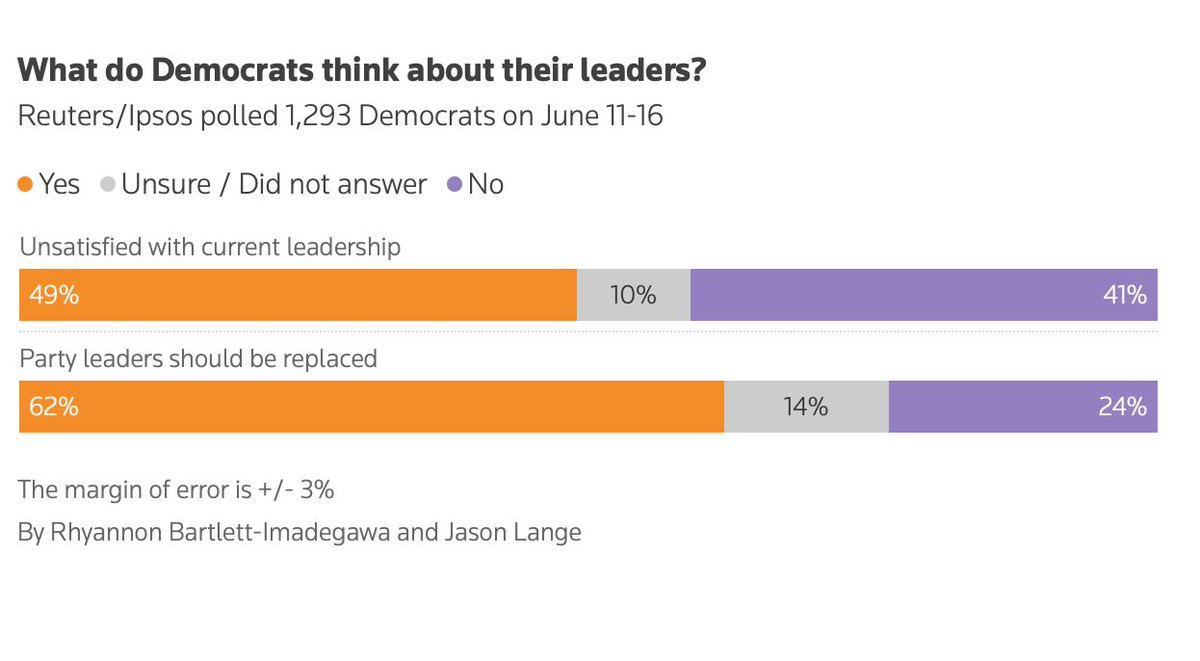

There is obvious demand inside the Democratic electorate for a new generation of pro-democracy, multiracial, working-class leaders. Poll after poll shows majorities of Democrats saying they want new voices at the top of the party. This is the closest either party has come to a Tea Party–style opening in more than a decade. Yet on the progressive side, the money and machinery that could turn that opening into a real faction are mostly missing. Liberal philanthropy has stayed cautious, like a venture fund that keeps talking about disruption while parking its money in blue-chip stocks. The vast majority of large donors to Mamdani’s primary against Cuomo were a small circle of Muslim and Arab Americans, not the big foundations and institutional givers that dominate liberal politics. They remain committed to familiar partisan and advocacy models and short funding cycles rather than the slow, unglamorous work of building an internal challenger wing. Zohran Mamdani’s primary exposed that gap as much as it showcased a candidate: the demand is there, the supply is still not.

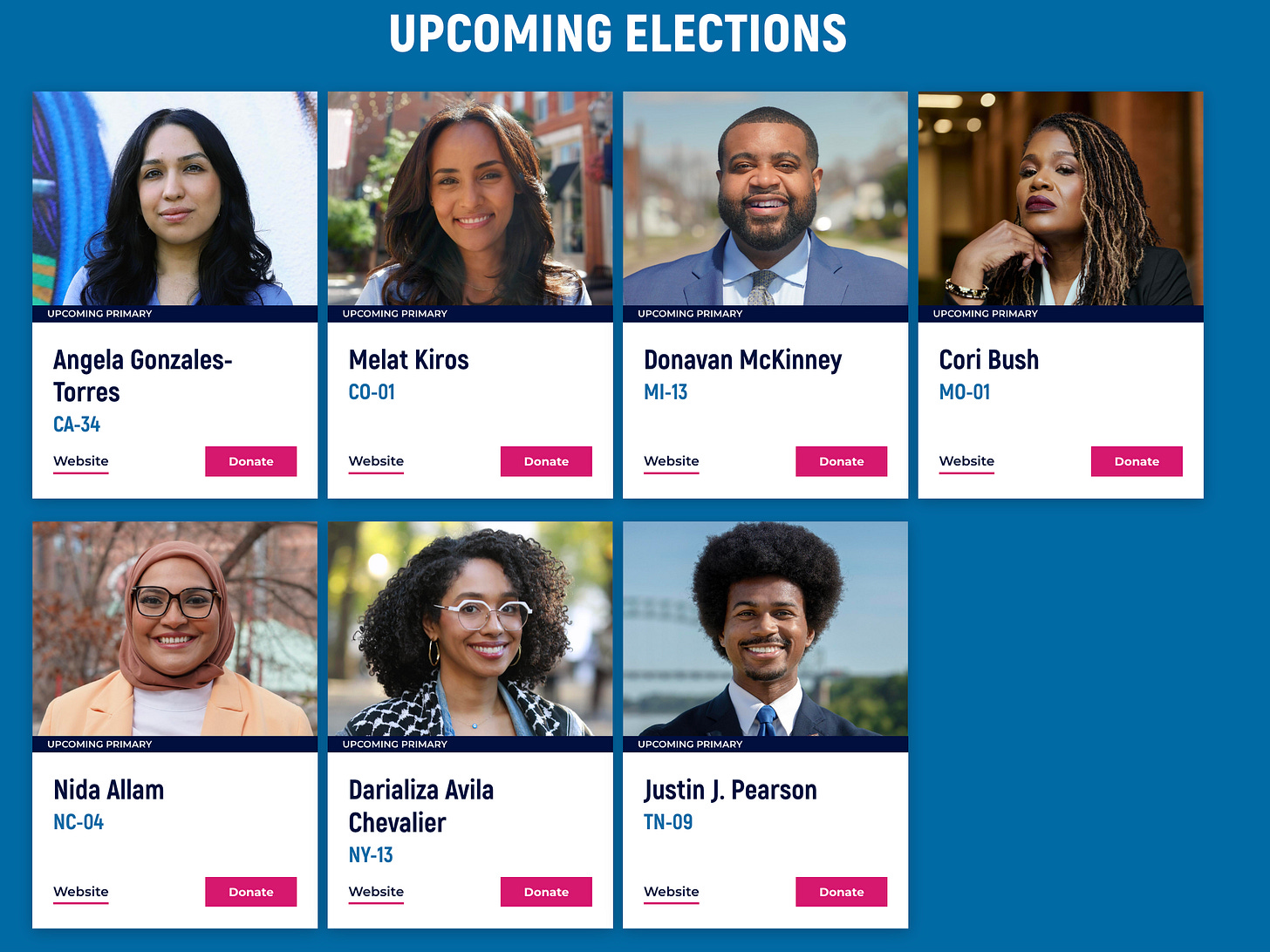

What’s required looks less like another pop-up PAC and more like a permanent farm system: aligned polling and message testing, candidate recruitment, staff development, independent-expenditure muscle, and basic governing prep that runs year-round instead of for six frantic weeks before a primary. Justice Democrats is by far the closest thing to that kind of operation—its staffers separately helped run the largest independent expenditure backing Mamdani. The organization has been central to electing a handful of the new members who now anchor the party’s left flank. They are trying to build a pipeline in Memphis, Los Angeles, New York City, Chicago, Durham, St. Louis, Denver, and beyond. But they are doing it on a fraction of the resources now pouring into AI and crypto lobbying—or into AIPAC’s effort to stop exactly these kinds of candidates from ever reaching Congress.

Justin Pearson’s race in Memphis is another test of this new faction. In a safely Democratic seat, a young Black organizer who helped lead the fight against Musk’s xAI “Colossus” project is forcing a simple question: should the party’s only House member from Tennessee stand with Big Tech’s AI buildout or with communities breathing in its fumes. If Pearson wins, it will not change which party controls the House, but it will send a clear signal about where the Democratic coalition stands in the next political economy and who gets to set the party’s line on Musk and AI at a time when the biggest tech companies are working hard to win over the party establishment.

“In a chaotic time, people who have a clear program often exert more influence than their numbers might suggest,” the historian Eric Foner has said.

Parties on their own tend to drift toward the lowest common denominator: vague language about “the middle class” and “opportunity” that offends as few factions as possible. What organized edges do, as political scientist Daniel DiSalvo has argued, is give the center concrete bones to work with: specific demands, usable frames, devils in the details. Morris’s affordability charts show what that looks like in real time, as one deep-blue primary produces a visible bend in the Democratic line and a way of talking about the economy that even Republicans start to copy. If Democrats want to be the party of people who cannot afford rent, child care, or a first home, they cannot rely only on swing-district triangulation; they need more Mamdani-style wins in safe seats that take risks, work out the substance, and help hand every Democrat from Zohran Mamdani to Mikie Sherrill a clearer story to tell.

I think we are headed for a Republican wipeout at the midterms but the most important thing is to break the grip of Zionism (AIPAC) on Congress and that means putting in Democrats that will not, once in place, vote for money and weapons for Israel. In my district, IL-9 we have three D candidates that will criticize Israel's actions in Gaza but will not criticize Israel itself. That is the clue that they are stealth candidates who will continue the historic and awful "special relationship" if elected. None of the three will answer my question, "will you pledge not to support Israel should you be elected?" All remain silent because they want the pro-Israel voters but feel safe in criticizing Gaza since almost everyone is doing so. My message to voters is to not be deceived. Pro-Israel billionaires are in a panic realizing that all their money cannot counter votes, yet they dare not fund campaign messages that mention Israel in a positive light. We the people MUST take our Congress back from Israel. Pro-Israel politicians belong in the Knesset, not in the US government.

Really thoughtful. I love how you described Mamdani's impact on opening up an entirely new conversation. In terms of Democratic leadership I thought you'd like my recent post on 7 reasons why Schumer must go

https://paulloeb.substack.com/p/seven-reasons-chuck-schumer-must

Also--I've been trying to reach you to use your wonderful piece on abolitionists challenging slave catchers in the third edition of my political hope anthology The Impossible Will Take a Little While, with 120,000 copies in print. I emailed via Substack and also reached out via LInkedIn, but if you could email me at paul [at] paulloeb.org I'd love to send you what I'd like to use. You can check the book out at www.paulloeb.org