How South Asian Turnout Redrew New York's Map

The 350% surge that flipped the map for Zohran Mamdani.

In most election postmortems, Indo-Caribbean and South Asian New Yorkers barely register. They’re folded into “Other,” rolled into “Asian,” or dismissed as a “hard-to-reach” universe that consultants gesture toward in memos and ignore in practice.

Not this year.

In the 2025 general election that elected Zohran Mamdani mayor, those same communities turned out at levels that would make a Midwestern swing county blush. According to DRUM Beats’ analysis of Board of Elections data:

Bangladeshi turnout: 15% → 49%

Pakistani turnout: 15% → 46%

Punjabi turnout: 14% → 37%

Indo-Caribbean turnout: 12% → 29%

Nepali turnout: 16% → 41%

Tibetan turnout: 10% → 35%

Indian turnout: 18% → 45%

The tempting way to frame this is as a story about one candidate: a charismatic democratic socialist cracks the TikTok code and surfs a wave of youth and left-wing enthusiasm into City Hall. The more interesting story is what the numbers actually describe: years of organizing in communities written out of formal politics finally showing up in the data. Once people who had been treated as background were invited into the electorate as protagonists, they behaved like every other serious bloc. They voted. According to DRUM’s analysis of Board of Elections data:

South Asian turnout rose from 15.3 percent in 2021 to 42.9 percent in 2025, and Muslim turnout climbed from 15.1 to 34.2 percent.

Across the broader Indo-Caribbean and South Asian communities, the total number of voters participating grew by roughly 350 percent over the same period.

South Asians and Muslims account for just 7 percent of the city’s registered voters, yet they cast an estimated 15 percent of all ballots in the general election. In a race decided at the edges, that is a decisive bloc.

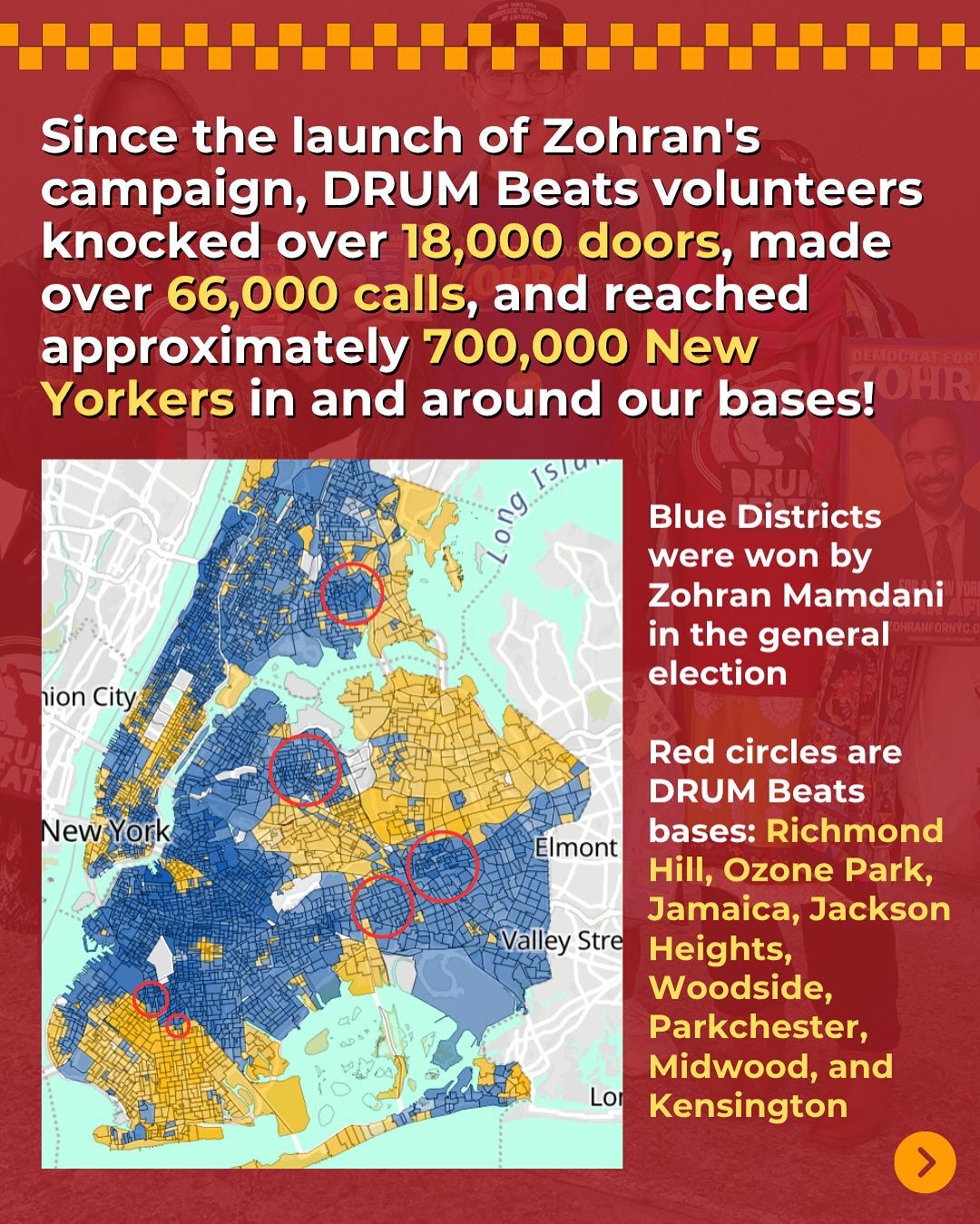

The steepest gains came in neighborhoods that keep the city running but rarely set its agenda—Richmond Hill and Ozone Park, Jamaica and Jackson Heights, Woodside, Parkchester, Midwood, Kensington. These are the places where DRUM Beats and allied organizers have spent years knocking doors, translating ballot measures, convening tenant meetings in basement prayer rooms, and building lists through WhatsApp groups and WhatsApp rumors alike.

As Michael Lange notes, neighborhoods like Ozone Park barely warranted a footnote in the last mayoral cycle; this year, national reporters were building their Election Day itineraries around them. Along Hillside Avenue—the Bangladeshi, Sikh, and Indo-Caribbean corridor where Mamdani first sought out disillusioned Trump voters—the democratic socialist didn’t drop a single block. Lange, who spent the day trailing Mamdani from Astoria playgrounds to church basements in Brooklyn, calls the outcome “unequivocally, the voter coalition the political left had always sought to build.”

There was nothing especially mystical about what happened next. When organizers show up in gurdwaras, mosques, mandirs, restaurants, taxi lots speaking Bangla, Urdu, Punjabi, Hindi, Nepali, and when the conversation is about rent hikes, medallion debt, school overcrowding, stop-and-frisk, and the cost of groceries and child care, the response starts to look familiar. Irish longshoremen and Jewish garment workers reacted similarly when someone finally bothered to connect their daily lives to the ballot.

To understand why this feels like a break, it’s worth remembering the recent past. After 9/11, Muslim, Arab, and South Asian New Yorkers were pushed out of public life and into surveillance regimes. They were monitored by the NYPD, hassled at airports, placed on registries. Politically, they were treated as radioactive—too angry about foreign policy, too frightened of law enforcement, too linguistically fragmented to justify real investment. When consultants labeled them “unreliable,” that phrase often disguised a simpler fact: no one had built the infrastructure that makes reliability possible.

The Mamdani campaign, working with groups like DRUM, CAAAV, and a web of smaller neighborhood organizations, set out to overturn that logic. Their premise was straightforward: if you speak to people in the languages they use at home about the pressures that define their week—rent that eats half a paycheck, crushing debt, long commutes, police harassment—they will respond like any other engaged constituency. Indo-Caribbean and South Asian voters were not treated as an add-on or a photo-op; they sat at the center of the campaign’s math.

That’s why Mamdani’s line—“We will fight for you because we are you”—was not just a flourish. When he stood onstage and thanked Yemenis, Bangladeshis, Guyanese, Pakistanis, Uzbeks, Trinidadians by name, he was reciting the coalition that had just delivered him a majority.

There is a familiar historical rhythm here. The parallel is less to a celebrity candidacy that briefly scrambles the map than to earlier moments when groups written off as threatening or foreign became disciplined voting blocs: Irish Catholics moving from despised outsiders to Tammany’s core; Jewish and Italian workers turning the Lower East Side into a labor/socialist stronghold. In each case, communities that had been treated as a security problem or cultural irritant discovered, with resonant leaders, that they could function as a a political bloc.

That lens also clarifies the awkward national comparison. Kamala Harris is both South Asian and Black, yet her presence at the top of the ticket did not, by itself, produce record turnout in either community. Symbolic breakthrough did not resolve the substantive questions many voters were asking—about Gaza and U.S. weapons policy, about rent and groceries, about whether Democrats would ever treat their neighborhoods as anything more than safe blue territory. For voters who felt ignored abroad and squeezed at home, identity without a shift in priorities read less like change and more like continuity.

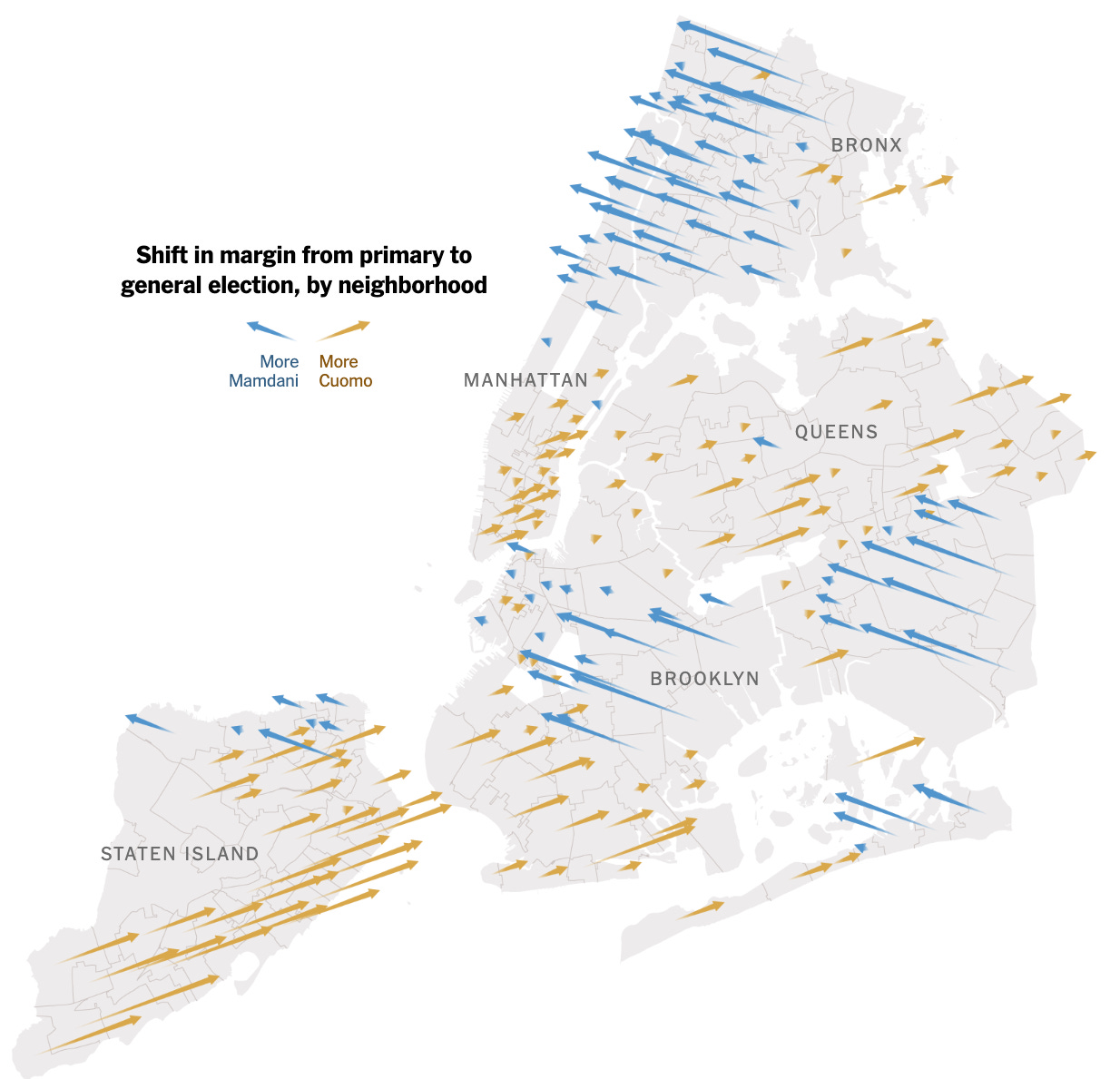

Seen from that angle, this wasn’t simply a left-wing outlier sneaking through a crowded field. I’m sure most of these voters do not identify as “liberals,” for instance. It was a set of voters long relegated to the margins moving decisively into the center of the story and rearranging the city’s arithmetic. New York rarely changes by quiet succession; its coalitions are remade by people no one counted until their turnout charts spike and the commentariat scrambles to catch up.

Indo-Caribbean and South Asian New Yorkers just had one of those inflection points. Lange casts Mamdani’s win as the newest chapter in New York’s Rainbow Coalition—a multiracial bloc of Black voters, Puerto Ricans, newer immigrant communities, and young, socialist renters. What’s different now is how central Indo-Caribbean and South Asian voters are to that coalition, and how much of it is rooted in neighborhoods that swung toward Trump only a year ago. Whether this was a peak of protest or the early architecture of the city’s next governing majority remains the open question.

Shahana Hanif’s historic win in 2021 — she was the first Muslim woman elected to City Council in District 39 which includes Kensington, where she was born and raised, as well as Park Slope — and her astounding re-election campaign this year — in which she got 70% of the vote despite an opponent backed by the same billionaires who attacked Mamdani and who relied on the same hateful Islamophobia and false accusations of antisemitism — definitely helped jump-start the increase in the participation of Bangladeshi-American voters.

Stories like this are what keep my faith in humanity alive.