Immigration: Not Just a Backlash, A Breakdown

In the ruins of pandemic recovery, the GOP told Latino voters they mattered—while Democrats asked them to wait.

Throughout American history, immigration has tested the shape and durability of political coalitions. Today is no different. But instead of articulating what’s at stake—or who immigration policy is meant to serve—Democrats and progressives ceded the field. The result was a vacuum, filled on one side by Republican restrictionism, and on the other by a moral absolutism that treats any deviation from idealism as betrayal. Into that void, a political earthquake began to stir.

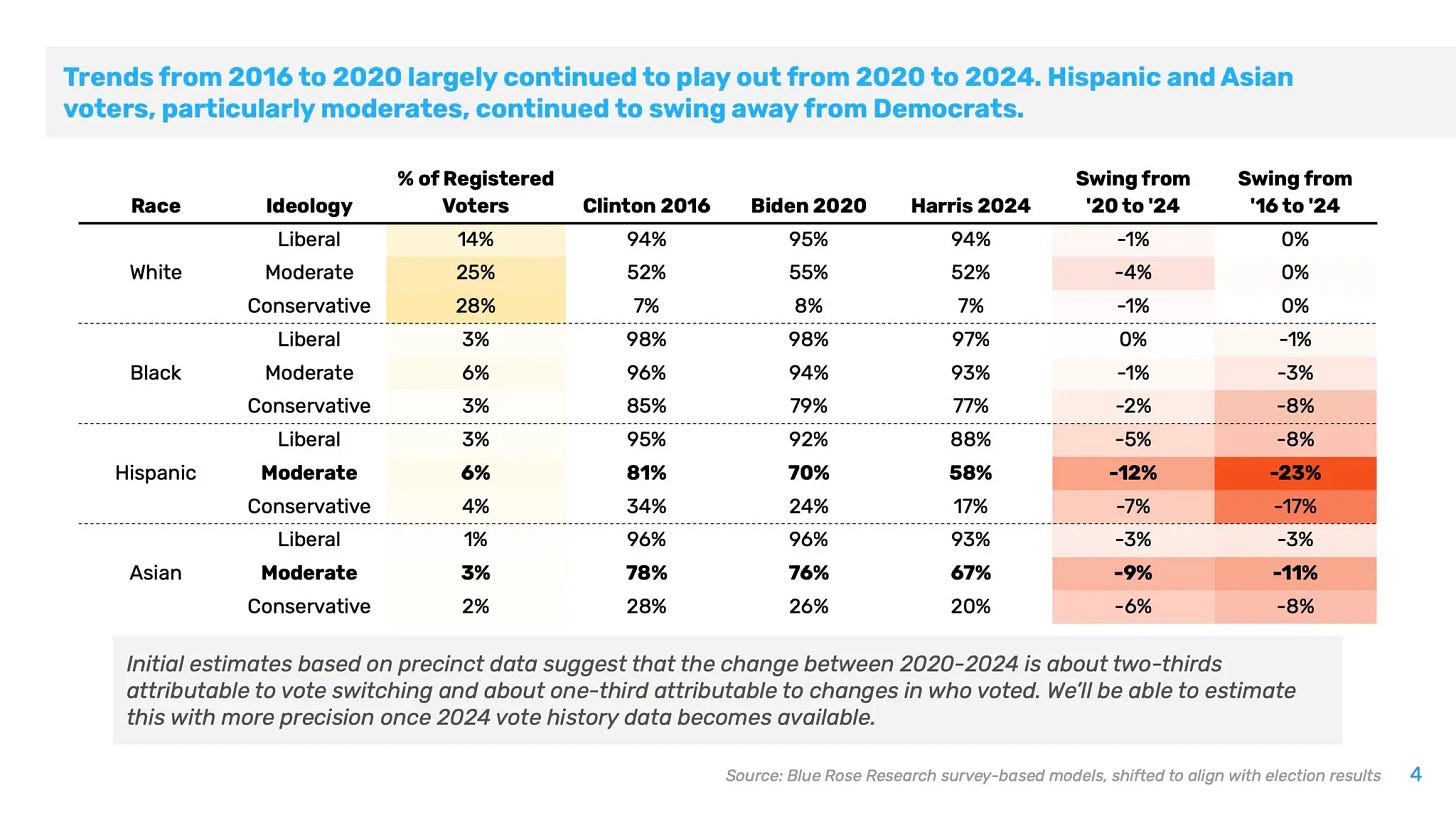

In an election dominated by Donald Trump’s most restrictionist immigration platform to date, the GOP nonetheless made startling gains among Latino and Asian voters, particularly working-class naturalized citizens. The very communities long assumed to be linchpins of the Democratic coalition—immigrants and their children—began to drift.

The shift is hard to ignore. Naturalized citizens, whom Biden carried by 27 points in 2020, swung toward Trump by up to 23 points, according to pollster David Shor. In some immigrant-heavy counties, Trump saw double-digit gains.

The irony is sharp: a campaign built on closing the gates was buoyed by many who had walked through them. Here’s Ian Haney Lopez describing the trend in 2020:

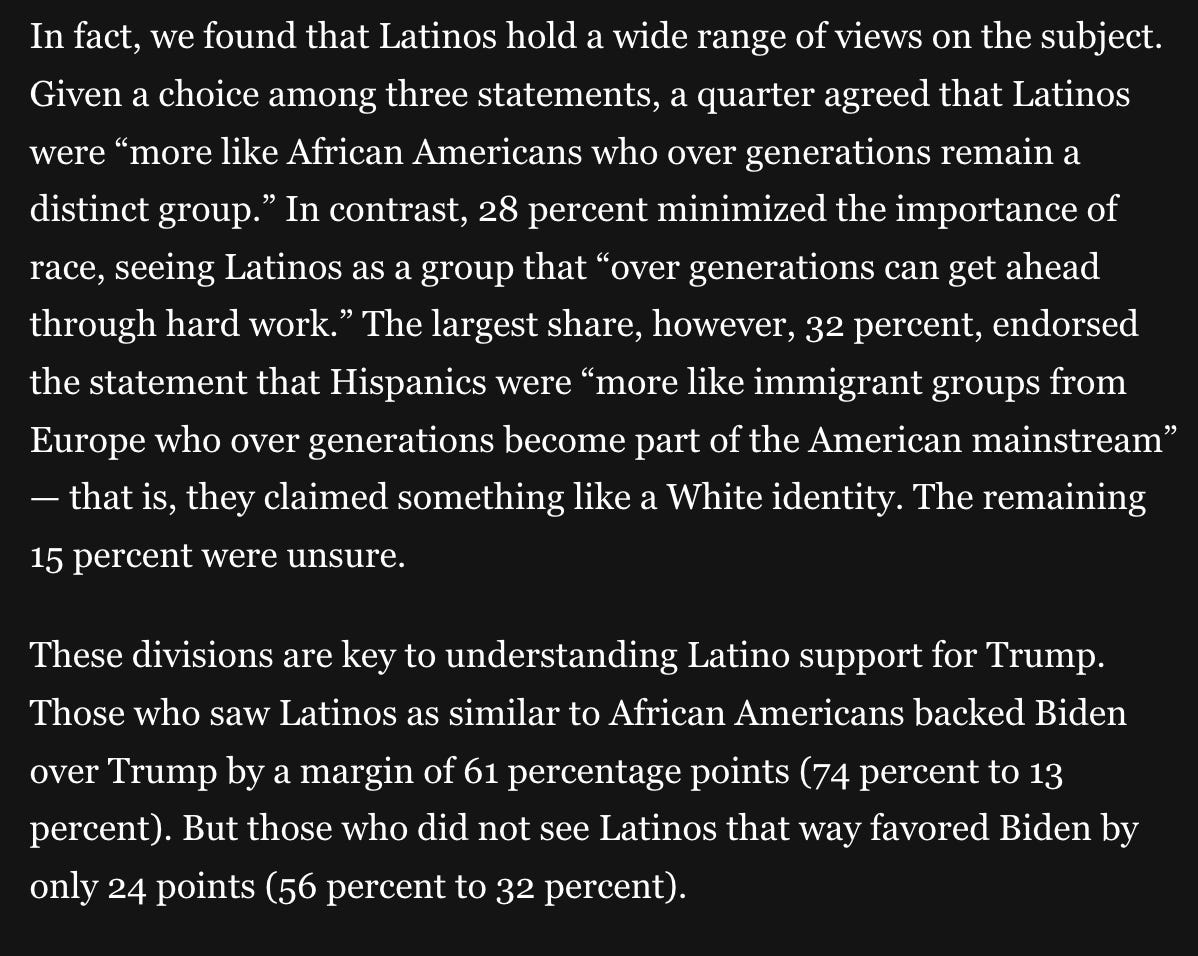

Part of what’s happening, as Haney López has documented, is not a rejection of identity politics but a shift in how identity is understood. His research shows that Latino voters don’t share a single racial self-conception. These identity frameworks align tightly with how people vote. Those who see Latinos as a marginalized racial group break heavily for Democrats. Those who see themselves as future insiders are more open to Republicans. What’s often framed as backlash is better understood as status anxiety—a hunger to be seen not as victims, but as contributors. And when Democrats offer no clear vision of belonging—no economic story, no recognition—that anxiety doesn’t go away. It just finds a different political home.

This isn’t merely a communications failure. It reflects a deeper identity and political rupture—what Daniel Schlozman calls the breakdown of “movement-party alignment.” In eras of transformation, movements and parties lock in: labor and the New Deal, civil rights and the Great Society, DREAMers and the Obama-era DACA and DAPA fights. Movements expand the moral imagination, shift public opinion, and create urgency; parties translate that urgency into policy, power, and governing agendas. But when those alignments collapse—when movements falter, constituencies shift, and parties grow incoherent—what follows isn’t policy drift. It’s realignment.

In 2024, immigration became the terrain on which a broader crisis of governance, identity, and coalition unfolded. Democrats struggled to match the mood of the country, offering neither competence nor vision.

Beneath the surface of the immigration debate lies a quiet economic upheaval—one felt most acutely by Latino men, as economic historian Adam Tooze has noted. With some of the highest labor force participation rates in the country, Latino workers are concentrated in industries like construction, hospitality, agriculture—the very sectors hardest hit by the COVID-19 shutdown. But the real transformation came afterward. When these jobs returned, they didn’t come back as they were. They reappeared under new terms: more precarious, more automated, more fragmented. From self-checkout kiosks to GrubHub gigs to algorithmic scheduling, the post-pandemic labor market pushed wages down and stripped work of stability.

For a brief moment, pandemic relief reversed this trend. Enhanced unemployment benefits increased the minimum wage effectively to $15 an hour. The Child Tax Credit cut Latino child poverty, benefiting 1 in 3 Latino children. But when those programs ended, the bottom dropped out. Child poverty surged in Latino communities by 9.3 points. In border counties, where wages were already low, it felt like an effective pay cut. The economic floor didn’t erode slowly—it disappeared.

“…1.3 million Latino children falling into poverty as a direct result of the credit being removed.”

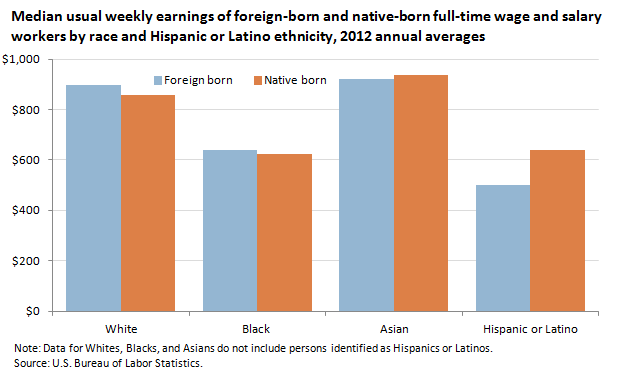

Overlay this with migration trends and the picture sharpens. Latino migrants are the exception to the rule that immigrants often out-earn native-born workers. They arrive with lower educational attainment, face language barriers, and are funneled into low-wage work. Native-born Latinos earn $947 per week on average; foreign-born Latinos, just $792. In sectors like construction or food service, the influx of new, often undocumented labor after the pandemic placed downward pressure on wages. And those who felt it first weren’t white-collar professionals—they were the last generation of immigrants, still clawing for stability. While newly arrived immigrants often start in precarious work, their upward mobility and growing participation in the economy generate long-term demand and economic growth—though those benefits take time to materialize, especially in communities already under strain.

As Haney López has argued, for men in low-status groups, masculinity can become a crucial claim to dignity—especially when traditional paths to status through work or education are eroding. That’s part of what Trump offered: not policy so much as posture—a way of performing toughness, control, and success in a world slipping out of reach. Stephanie Valencia of EquisLabs called this in 2021 “Trump intrigue”—a fascination rooted in his image as a blunt, self-made businessman, someone who, despite the bluster, seemed to move with power and purpose. And as Eric Garcia noted in 2021, younger, working-class Latino men often moved through the same media pipelines as their white peers: Rogan clips, Facebook memes, talk radio, Newsmax. For a group shut out of cultural and economic power, status—not just ideology—was on the ballot.

This is not just a story of cultural backlash. It’s one of material competition and unmet promises. When new arrivals strain shelters, classrooms, and hospitals in communities already under pressure, residents don’t need Fox News to feel anxious. When public systems fail those already here—offering no housing, few jobs, and overloaded schools—resentment grows fast and deep. And when that resentment is ignored or moralized away, the political consequences become clear.

Immigration became a proxy for broader breakdowns: in housing, in schools, in the labor market, in government responsiveness. And into this breach stepped the right, with a story as blunt as it was effective: the system is broken, and Democrats are to blame.

Despite the familiar narrative that activists drive the Democratic Party leftward, the story from 2022 to 2024 suggests the opposite: a relative retreat of movement energy left a hollowed-out party without the ideas or pressure to act. Movements had once led—shaping the moral terms and forcing institutional response. But without a public organized around a solution, the party offered drift, not direction. The disruptive, often bilingual, emotionally resonant tactics that once defined the immigrant rights movement—the 2006 “Day Without an Immigrant” marches, the DREAMer campaigns of the Obama years, the airport protests against the Muslim Ban, the national outcry over family separation—had not come from party elites or policy shops. They had come from the ground up, reshaping public opinion through moral urgency and public spectacle.

But in the face of rising asylum claims, escalating political attacks, and an information environment saturated with crisis coverage, few similarly forceful interventions broke through. The activist voices that once compelled the nation to pay attention had either gone quiet or been crowded out by a media ecosystem more interested in Greg Abbott’s partisan theater. And despite the right’s claims of progressive overreach, asylum seekers and their advocates were strikingly scarce in mainstream coverage. Their absence revealed not saturation, but a vacuum—one in which the harrowing stories of migrants were rarely heard enough to shape the national debate.

By 2024, that vital alignment between constituent organizing, media visibility, and the party’s institutional response had broken down. There were few major marches or breakout leaders commanding national attention in response to Governor Greg Abbott’s busing, no coherent counternarrative. By 2024, even the 11 million undocumented immigrants who had lived in the U.S. long before Trump took office—once central to the movement’s moral and political demands—had become more unheard and invisible than ever before. Asylum seekers themselves were largely voiceless in mainstream media, their stories buried beneath bureaucratic delays and political paralysis. The moral clarity and organizing strength that once pushed immigration into the center of American politics from 2006-2014 had dissipated just as the issue returned to the forefront—leaving a vacuum the right was all too eager to fill.

Caught between principle, stasis, and pragmatism, the Biden administration offered none—just drift until it was too late. The White House appeared sluggish, reactive, and out of touch, as if asleep at the wheel during one of the most visible immigration surges in recent memory. Moderates mouthed Republican slogans about enforcement but failed to outmaneuver a party that has spent years promising mass deportations and walls. Progressives clung to humanitarian rhetoric, but couldn’t connect it to the economic anxieties shaping voters’ lives.

The right, by contrast, moved with speed and clarity. Their message was blunt: immigration is out of control, and it’s making your life worse. Without a Democratic counter-narrative—no vision, no urgency, no story big enough to hold the contradictions—Republicans didn’t just win the policy fight. They set the terms of the era.

Anat Shenker-Osorio reminds us that a central strategy of authoritarian politics is inversion: persuading the public that the powerless have taken control. In this upside-down narrative, immigrants, trans people, Muslims, and movements like Black Lives Matter are cast not as marginalized, but as powerful threats—obscuring the actual hierarchies of power and justifying ever more extreme policies.

But American politics remains thermostatic: overreach generates backlash, and repression often awakens new coalitions. The challenge now is whether the backlash to Trump’s promised mass deportations and hate-for-profit politics can be translated into durable political power. Doing so will require more than moral clarity or reactive defense. It demands organizing grounded in the material realities of inequality in the post-pandemic era—realities that reshaped the lives of Latino working- and middle-class families, many of whom faced economic collapse, rising precarity, and institutional abandonment.

These voters are not peripheral to the immigration debate; they are at its center. Their labor sustained the country through crisis. Their children fell into poverty when pandemic relief was stripped away. And their political choices now shape the boundaries of what immigration reform can become. For too long, Democrats treated immigrants, especially Latinos, not as a constituency to persuade, but as a moral certainty. But coalitions are not guaranteed by demographics or virtue. They are political constructions, sustained through trust, delivery, and attention.

One bright spot for Democrats came in Arizona, where Ruben Gallego defeated Republican Kari Lake—an unpopular nad polarizing figure, in a purple state defined by immigration politics and demographic change. Yet Gallego’s vote for the Laken Riley Act—a Republican messaging bill that stripped due process from immigrants and drew constitutional objections from the ACLU—revealed the strategic limits of that centrist posture. Gallego secured no concessions, reportedly irritated party leadership, and lent bipartisan legitimacy to a deportation-first agenda that does little to address the root causes of immigration anxiety.

At the other end of the party spectrum, Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are articulating a more foundational critique. Sanders has been blunt about the Biden administration’s failures on immigration enforcement and border management, but rejected the Laken Riley Act, strongly opposed the abduction of Mahmoud Khalil, and warned that Trump’s plans for mass deportations would not only be immoral but economically catastrophic—disrupting industries that rely on undocumented labor. Ocasio-Cortez, meanwhile, takes a civil and human rights approach, emphasizing the role of immigration enforcement in eroding due process and scapegoating migrants for broader systemic failures: “You’ll never deport your way to affordable rent.”

The tension between these poles captures the unresolved future of the party. And it’s a future that will be shaped, in no small part, by continued migration driven by inequality, violence, and climate upheaval—forces that are not episodic, but structural and enduring.

When parties grow complacent and movements recede, coalitions don’t just weaken—they unravel. The task ahead is to reimagine immigrant rights not just as a liability to be tiptoed around, but as a foundation for democratic renewal, economic justice, and multiracial solidarity. Whether that vision takes hold—or immigrant politics hardens into fear, silence, and division—will help determine not just the future of American democracy, but whether the next era of economic policymaking includes the very workers — citizen and non-citizen — keeping industries afloat, or leaves them out of the deal once again.