Kamala, Kerry, and the Familiar Folly of Democratic Autopsies

In 2004, Democrats blamed gay marriage and Iraq; in 2024, it’s wokeness—while voters’ top concern in both elections was the economy.

Kamala Harris’s 2024 loss has Democrats retracing the same steps they took after John Kerry’s defeat in 2004, facing familiar questions about how to reach Middle America’s concerns about gay marriage and terrorism and counter the right’s cultural messaging machine. Back then, they worried about evangelical voters and the NRA; today, it’s influencers like Joe Rogan and Andrew Tate pulling in alienated men.

Here’s Nicholas Kristof and a senior Democratic elected official after Kerry’s loss in 2004:

Senator Feinstein’s suggestion that same-sex marriage energized a conservative backlash echoes the concern that cultural progressivism risks driving away the base. But the truth Democrats faced then—and face now—is that the problem wasn’t about lacking the right distribution channels; it was not having a compelling enough message.

Hillary Clinton’s aides argued that after Kerry’s loss, Democrats needed a moderate who wasn’t against the Iraq War.

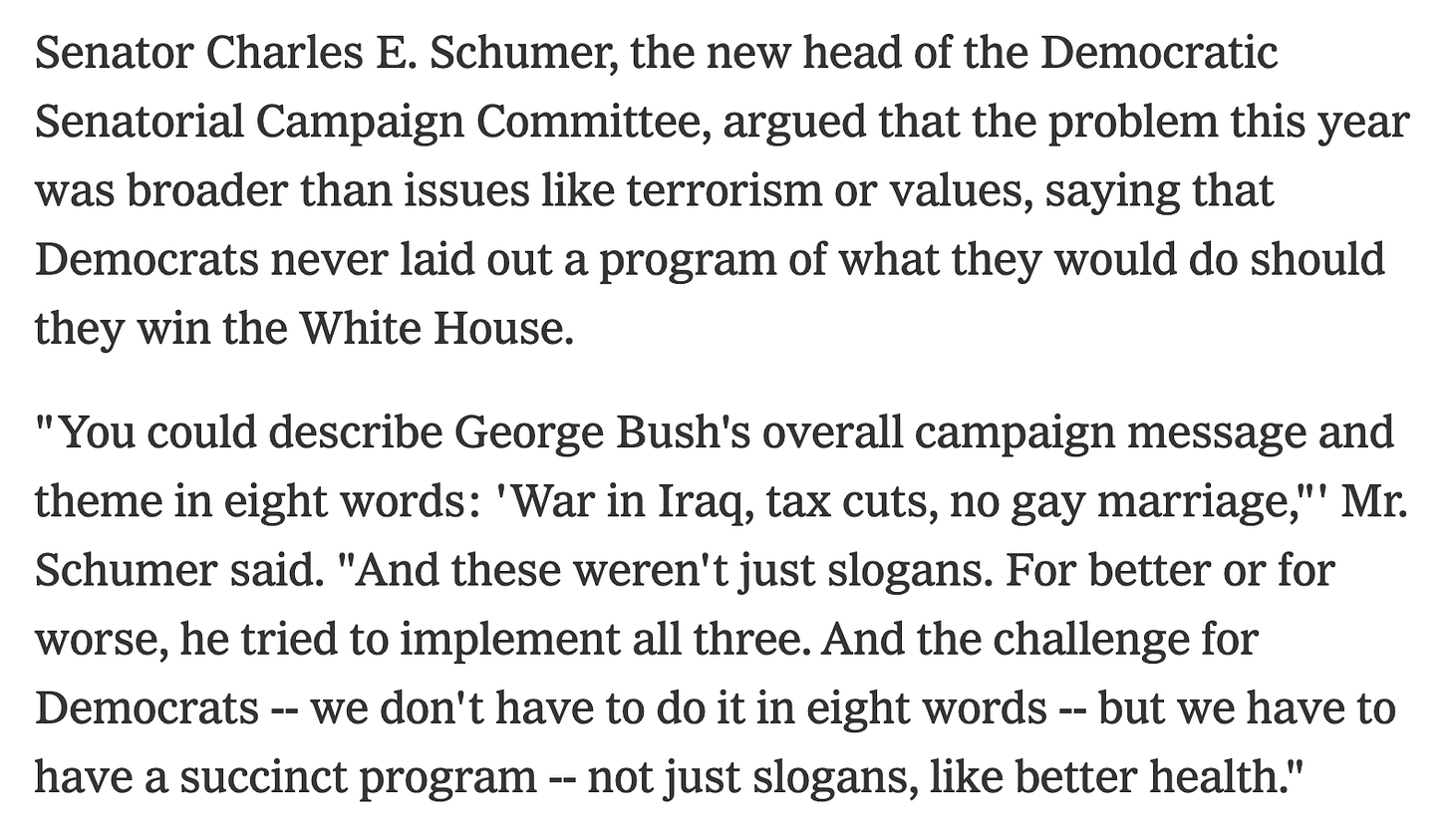

Senator Schumer argued that Republicans could sum up Bush’s campaign in three words: “War, tax cuts, no gay marriage.” But Democrats, as Schumer admitted, “never laid out a program” of what they’d do if they won. They wanted power but hadn’t defined a purpose.

In The Argument, Matt Bai describes how, after Bush’s victory in 2004, Democrats grappled with tough truths. While they initially blamed evangelical voters and the conservative media machine, a post-election analysis from John Podesta’s Center for American Progress showed Bush had won support from key demographics like Latinos, women, and Catholics. It turned out many religious voters cared more about economic stability and the Iraq War than about gay marriage or abortion.

Disheartened, Democrats searched for what Bai called “the Thing”—a unifying purpose that could rally their base and expand their reach. What followed was an assumption that they’d have to mimic conservative values to win over middle America. But in 2008, Barack Hussein Obama—an anti-war, left-of-center candidate—reframed Democratic Party politics. He didn’t just echo values; he tapped into the country’s mood, promising transformative change. As Ezra Klein has noted, if you examined the 2004 postmortems, few could have predicted that Obama—a vocal critic of the Iraq War and someone seen as leaning to the liberal side—would soon emerge as the Democratic nominee.

The lesson from 2004 is one Democrats can’t afford to forget: creating liberal versions of Joe Rogan to sell a lackluster product won’t cut it. Trump’s appeal isn’t just about the media channels his allies use; it’s in the pitch he’s delivering—a vision, however bleak, that speaks to real change. His authoritarian critique of democracy, his relentless blame of Biden and Harris for inflation and global disorder, his strongman persona, and his promise to protect society’s hierarchies tap into a craving for order and action. For frustrated voters, Trump offers clarity and direction—a clear response to problems Democrats too often seem to middling and a defense of democracy’s inability to deliver change.

Trump doesn’t just wage culture wars; he offers an alternative to democracy’s gridlock and messiness. Democrats, meanwhile, seem mired in process, urging patience and compromise but struggling to outline what they’re delivering. The real challenge isn’t influencers or infrastructure—it’s offering a vision that’s as tangible and bold as Trump’s but grounded in something voters feel will genuinely improve their lives.

Bharat Ramamurti, Biden’s former Deputy Director of the National Economic Council, pinpoints a core misstep in the Democrats’ 2024 strategy: policies that looked strong on paper but felt too distant to voters struggling with immediate costs. Policies like clean energy investment, capping Medicare costs and building new housing units are smart, even essential—but their impact is delayed.

In an economy where inflation is eating away at household budgets, waiting for relief that kicks in years down the line is a hard sell. Ramamurti underscores the need for Democrats to prioritize speed and immediacy in their agenda. Voters aren’t asking for promises; they’re asking for results they can feel today, not just down the road. To win in a volatile political landscape, Democrats need to think less about long-term positioning and more about delivering concrete, immediate wins that meet voters where they are.

After 2004, strategists like Simon Rosenberg and Rob Stein tried to mirror the right’s network of think tanks, media outlets, and grassroots organizations, aiming to build a liberal counterweight. But instead of a clear ideological stance, they defaulted to negative partisanship—focusing on beating Republicans rather than defining why they should win. As Stein’s Democracy Alliance meetings showed, many Democratic donors feared risky ideas that might upset their own base, leading to a fragmented, cautious message that lacked the ideological clarity of the right. Instead of driving a movement, Democrats seemed more intent on retaining power, a strategy that’s proven thin and unsustainable.

The 2016 and 2020 campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren should have been a wake-up call for Democrats. Nearly half of the primary electorate backed candidates who argued that the economy, government, and democracy itself are stacked against ordinary people. Sanders’ campaign wasn’t about incremental fixes; it was a blunt critique that wages are stagnant, healthcare inaccessible, college too expensive, and corporations too powerful.

Yet, rather than embracing these demands for systemic change, the Democratic establishment often sidelined or softened them, stripping away their populist urgency. The Democratic establishment’s discomfort with Sanders-style populism isn’t just about policy; it’s about tone and taste. Many upper-middle-class liberals and donors who make up the cable news class see his blunt, urgent approach as unsettling—too disruptive to the decorum they associate with preserving democratic norms. This group prefers a restrained, technocratic style that signals stability, competence, and moderation. But by softening the demands for systemic change, Democrats lost the immediacy and populist edge that could have resonated with the economic frustrations of a broader base.

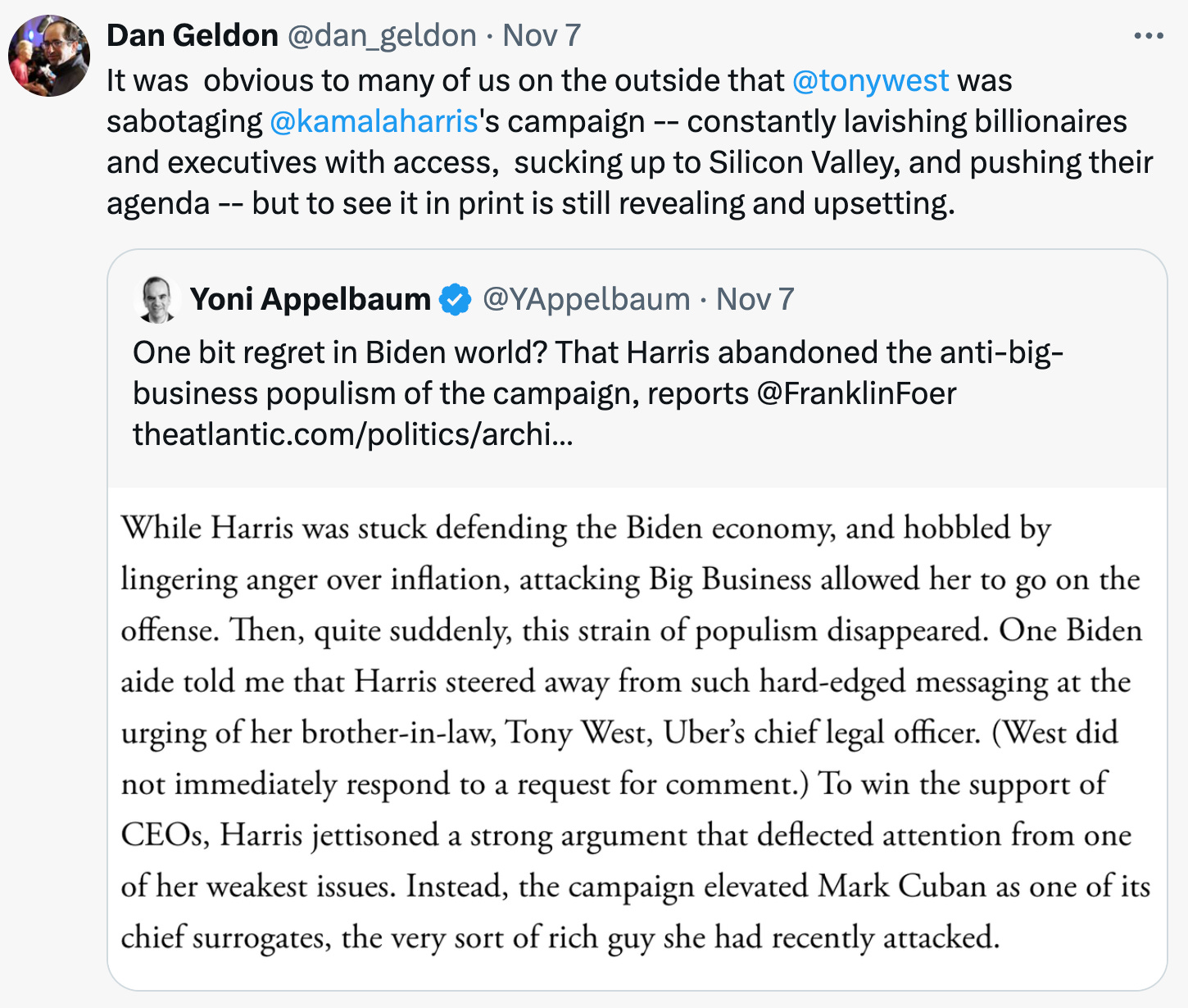

Blaming progressives for the Democrats' 2024 loss is absurd. Even Bill Kristol, a Never Trump conservative, urged Kamala Harris to embrace a bold, populist message like Elizabeth Warren’s Ultra-Millionaire Tax to counter Trump’s billionaire backers. With voters struggling to name a single economic win under Biden, the campaign’s reluctance to lean into a strong populist message of change left a void that Trump eagerly filled. Harris had the chance to go on the offense by taking on Big Business, but, reportedly under advice from her brother-in-law Tony West, she pulled back, elevating billionaires like Mark Cuban as surrogates instead.

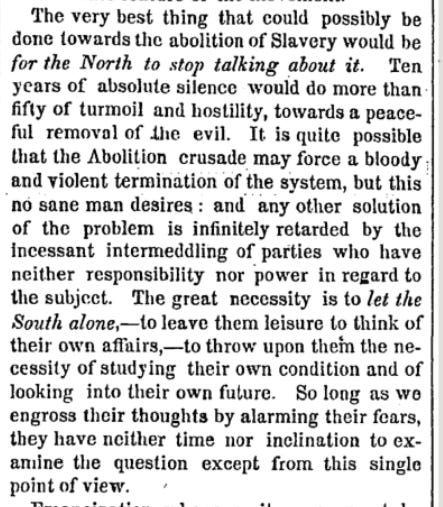

The friction between parties and movements is as old as democracy itself. In 2004, Democrats pointed fingers at gay marriage advocates for John Kerry’s loss to George W. Bush, just as the New York Times editorial board in the 1850s chastised abolitionists, suggesting that “the very best thing that could possibly be done towards the abolition of slavery would be for the North to stop talking about it.” To be clear, this isn’t to equate today’s issues with slavery, but the pattern is familiar: movements, whether advocating for climate action, immigration reform, or trans rights, are often seen as disruptive or inconvenient.

Civil society and movements thrive in the U.S. precisely because our two-party system often gravitates toward a safe, centrist consensus, sidelining voices that don’t fit into neat electoral strategies. These movements push for change that the parties might otherwise avoid, dragging essential, uncomfortable issues into the spotlight. This is a dynamic that is never going away and Democrats have to learn how to play ball. Rather than wishing them away, Democrats should see these movements as real as the laws of gravity. Learning to navigate this tension isn’t a distraction—it’s a fundamental part of leading in a democracy.

Yes, movements aren’t always strategic; they sometimes lack persuasion.

On issues like trans rights and asylum, these aren’t just progressive causes—they’re real shifts happening in society, and they’re not being driven by a tidal wave of advocacy dominating the airwaves. In fact, we see surprisingly few trans rights or asylum advocates in mainstream media, and that says something: these movements might not need to be cast aside but better resourced for persuasion.

A well-coordinated public relations and organizing effort could have helped—offering stories and voices that contextualize and humanize these issues—instead of leaving the space open for anti-immigrant and anti-trans narratives to take hold. Instead, the message from philanthropy and the narratives of establishment consultants was that pushing for persuasion on these issues risked sparking an electoral backlash. Americans might have benefited from hearing from trans people and asylum seekers, seeing these issues not just through the lens of culture wars but as lived realities. A stronger, well-resourced response could have countered the urge to pivot to Trump-lite stances or ignore the issues altogether.

Democracy is inherently messy, with movements and parties clashing as they advocate for different priorities. The lesson isn’t to hippy-punch left or silence activists but to learn how these tensions can coexist productively. It’s not the Sunrise Movement or AOC who ran the 2024 campaign—it was Biden, Harris, Liz Cheney, and the party’s establishment for the past two decades. After four years, voters aren’t asking for silence on tough issues; they’re asking, “What did you actually do for us?”

Without a clear answer, far-right extremism fills the void. In the face of rising authoritarianism, the task for Democrats is to put forth a vision of democracy that delivers concrete, visible results—one that doesn’t just defend democratic values but shows how those values improve people’s lives.

Every single election cycle, the GOP invents a new scapegoat. Sometimes there is an underlying true fact (trans surgery for prisoners - approved under Trump!), sometimes it's pure lies (eating cats and dogs). We should go back each cycle and document each scapegoat- in the 2022 NY races it was prisoners released because we ended cash bail.

If we did this exercise, our takeaway wouldn't be to argue over each year's scapegoat - it would be to anticipate each year's scapegoat and counter-attack immediately, effectively and as hard as we can. And by counter-attack I don't mean saying "It's Not True!" - instead we attack the underlying strategy that drives it, which is scapegoating.