Our Crisis Isn’t a Failure of Manners

On Ezra Klein, Charlie Kirk, and the civility trap.

In the days after a horrific political assassination, a familiar prescription returns: lower the temperature, insist on one another’s humanity, model disagreement without hatred. Ezra Klein has made that case in print and on air with Ben Shapiro and Utah governor Spencer Cox. Klein is right about the floor: we do have to live here with one another. In a brutal season, that sounds like relief and even hope.

But the heat isn’t where we keep pointing. Dialogue comforts because it is personal and immediate; it offers something each of us can do. Over time a faith has formed around that comfort—the belief that better manners can fix what only better rules can. Call that faith civilitycraft. It is the cousin of what Barbara and Karen Fields call racecraft, a social magic that turns effects into causes. Once upon a time, failed crops were explained by conjuring witches. In our politics, democratic breakdown gets explained by conjuring bad manners. If only we disagreed more gently, the spell suggests, the system would right itself and we would heal. The ritual soothes; the wiring remains the same.

Liberals long ago stopped believing that civility could stop mass shootings. We don’t tell parents mourning at Sandy Hook or Uvalde that the answer is better arguments; we talk about structure—laws, regulations, accountability. One day, we may look back on political violence the same way: recognizing it was never a failure of manners but of machinery, and that rituals of civility could no more contain it than “thoughts and prayers” could end school shootings.

Klein does not treat words as cure-all; his work on polarization is an extended argument about how institutions harden conflict. Those of us who live by words have a professional bias. We overestimate what language can do and underestimate what rules and incentives do. When your tool is a microphone, everything looks like a message. So we prescribe op-eds, panels, “national conversations,” as if they move history the way they move an audience. Culture matters. But culture is bent—daily—by law, design, and payoff structures.

Civil rights leader Bayard Rustin reminded his contemporaries of a hard truth:

“But in any case, hearts are not relevant to the issue; neither racial affinities nor racial hostilities are rooted there. It is institutions—social, political, and economic—which are the ultimate molders of collective sentiments. Let these institutions be reconstructed today, and let the ineluctable gradualism of history govern the formation of a new psychology.”

James Baldwin also gave the measure of that gap: “I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do.” In the days since Kirk’s death, much of the commentary has softened his politics into a tale of civility and persuasion. It is an old American habit: to look away from the words themselves in order to craft a more flattering memory. As Ta-Nehisi Coates described in his piece on Klein, the Confederacy was once recast as chivalry rather than slavery; the architects of Jim Crow were remembered as guardians of genteel order rather than destroyers of democracy. To treat Kirk as a symbol of polite persuasion while ignoring what he actually said is civilitycraft at work—elevating a story about tone while leaving untouched the machinery that rewards escalation.

If civilitycraft becomes a ritual, this is the machinery it leaves untouched. Political scientist Lee Drutman describes a winner-take-all, two-party design that trains ordinary disagreement to behave like a crisis. The dynamic is not symmetrical. A sorted Republican coalition, nested in minoritarian institutions, has radicalized first and furthest; the result is asymmetric escalation that drags the system toward the cliff.

When every seat is all-or-nothing and safe districts are decided in closed primaries, the loudest faction inside the GOP is rewarded. The Senate and the Electoral College allow a numerical minority to govern, raising the stakes of every contest. Gerrymanders lock in advantages. And when you plug all of that into an attention market that profits from outrage, the system starts cutting checks to arsonists. Civilitycraft asks for cooler tone while the circuitry keeps turning up the heat.

As Drutman argues, the doom loop functions like a microphone feeding an amplifier. The circuitry is built to escalate. Civilitycraft asks us to lower our voices; the rules keep turning the volume up. When majorities can’t see action on widely supported policies (guns are the clearest case), faith shifts from ballots to spectacle.

Kirk practiced a politics built for this incentive structure: combative campus tours, constant confrontation with liberal institutions, and a message machine tuned to culture-war mobilization. That doesn’t make him responsible for his own murder—it was horrific and wrong. It helps explain the far-right response to the murder: in a winner-take-all system where the out-party is cast as an existential enemy, the crime is quickly folded into a story that justifies escalation—collective denunciations, demands for crackdowns, delegitimization of the opposition. That is the doom loop at work: tragedy becomes fuel for hardening the trenches because the rules reward the leaders who harden them.

What we need isn’t nicer talk but different incentives. The point isn’t to end conflict; it’s to build a system that can carry it. Proportional representation—built here with multi-member districts and ranked-choice ballots—lets a diverse country step out of binary, zero-sum combat. Instead of two parties fighting for total control, several parties have to bargain in public; more voters see themselves reflected, and fewer elections hinge on destruction. Candidates must earn second-choice support, so reaching beyond a narrow base pays. Defeat still stings, but it no longer means erasure—and when losing is survivable, people stop looking for answers outside democracy. In other words, it makes nihilism costlier and coalition more rewarding—which is why it cools the temperature without asking anyone to whisper.

None of this means abandoning the call to refuse contempt. As political theorist Chantal Mouffe reminds us, politics is not the pursuit of consensus but the management of conflict. Her idea of agonism is simple to state: democracy is healthiest when it converts enemies into adversaries, when people can struggle hard over values and power but accept one another’s right to compete. The task is not to abolish conflict but to contain it—to make losing survivable and bargaining routine. America’s 18th-century institutions do the opposite. The Senate and the Electoral College let minorities govern majorities; single-member districts squeeze a plural country into two hostile camps. These rules don’t channel conflict, they intensify it. And that is why civility, however noble, feels powerless: the American system denies the agonistic space that democracy needs.

Klein is often caricatured as “be nicer.” I don’t think that’s his argument. His insistence is that a politics unable to absorb disagreement invites the gun. The complementary thought here is that absorption depends on design.

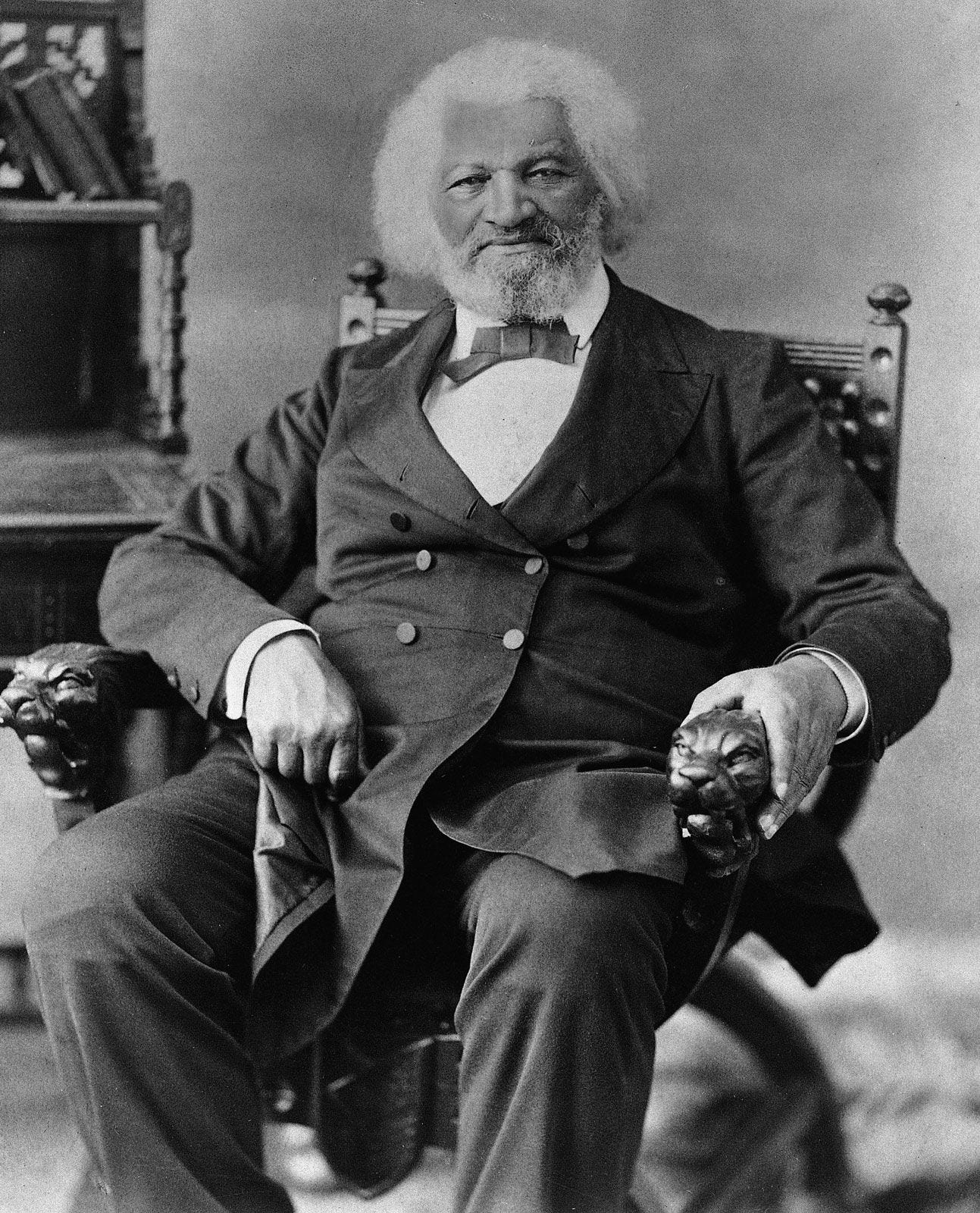

So we end where Frederick Douglass began: with the difference between eloquence and power. In his famous “Fourth of July” address, he mocked the notion that polite persuasion could undo slavery:

“At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder.”

Free speech covers Douglass’s fire and Kirk’s provocations alike; the First Amendment protects both. The question is whether institutions can hold that clash without turning it into a death match. Where power is shared, dissent becomes bargaining. Where it isn’t, dissent calcifies into resentment—and resentment slides toward violence. Democracy doesn’t survive by ending conflict but by bounding it, making defeat painful but not terminal. Ours too often fails that test, rewarding those who best treat politics as total war.

That’s why Douglass’s rebuke still reverberates. He was speaking against civility without consequence—the genteel request to quiet down in the face of cruelty. The Rev. Howard-John Wesley made a similar point in his viral sermon after Kirk’s assassination: condemn the killing, but don’t be coerced into hagiography or told to silence your own pain for the sake of unity.

Protect nonviolence and decency, by all means; the country needs it. But when injustice and corruption are entrenched, thunder often matters more than gentle showers. We won’t talk our way out of the doom loop. We’ll have to build our way out—rules and incentives sturdy enough to carry conflict without breaking the republic.

Civilitycraft asks for gentle showers—unity rituals, compulsory mourning, public hagiography, bipartisan pats on the back. Douglass reminded us that prophetic fire is also speech, and democracy has to be built to hear it without demanding whispers or reverence. That’s the work of democratic institutions: to channel conflict into rules and outcomes, not rituals of deference.

Excellent post that deserves amplification. The insights here are much more than food for thought, they stongly suggest a call to intelligent action. Here's a start: make ranked choice voting the norm and the law.

A very good essay. Point taken.

Two things that Trump has done cement my belief that he has no business in the White House. First, he removed the bust of MLKJ from the Oval Office and then more recently, he ordered flags to be displayed at half-staff to honor Charlie Kirk.

I confess I had not heard of Kirk until the news of his death, but then I started looking at what he said.

Kirk did not speak to all Americans, but to white Americans. His view of where power should be was patriarchal. He had nothing to say to people of color. His audiences, like the Republican Party, were almost entirely white and his message was one of victimhood, of wrongs done to the most privileged Americans. The name of his group, Turning Point, implies a reversal of the expansion of rights to so many who were denied them in practice if not in law. Though I did not hear him say it, he could easily have said certain people need to be put in their place.

MLKJ spoke to all of humanity. He addressed whites as "my white brothers and sisters" even as they cursed him and even threw stones at him in Cicero, IL. His efforts to speak for the undeniably powerless and victimized at the risk of his life was always seen. His most famous speech mentioned individuals being judged by the quality of their character and not the color of their skin. I don't know if Kirk had a name given to him by his detractors, but MLKJ was referred to as "Martin Luther Coon" by a good number of his.

One could not find a greater contrast than that between Kirk and King. The former would have felt comfortable in the Old South and certainly in the current South, while King would have likely been lynched in the Old South for not "knowing his place"

We have a bigot in the White House. His actions regarding Kirk and King cry out to all of us to do as King recommended and judge the individual by his character. That judgement would not be difficult as it is confirmed almost daily. I repeat: The man has no business in the White House. He does not represent we the people.