Progressive Electoral Strategy (1850s Edition)

How radicals, moderates, and conservatives fought over safe seats, swing states, and the soul of the Republican Party.

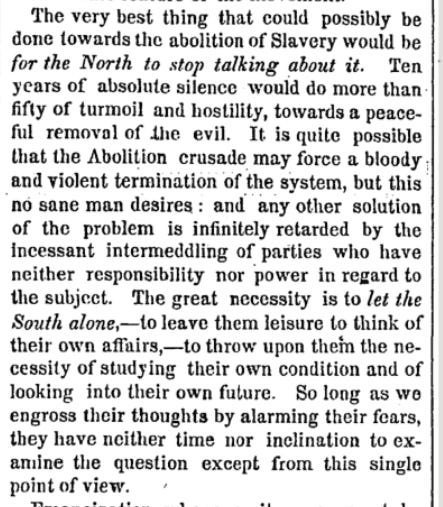

Open a nineteenth‑century newspaper and you can hear today’s intra‑party Democratic quarrel. In 1859 the New York Times scolded that “the very best thing that could possibly be done towards the abolition of Slavery would be for the North to stop talking about it,” proposing “ten years of absolute silence” to hasten a “peaceful removal of the evil.”

A year later, another NYTimes piece warned that if Lincoln won, “he will have to cut off the Abolition and extreme wing of his party; otherwise he will go by the board,” because a “practical, common‑sense man, and an old Whig, would reject the radical Republicans.”

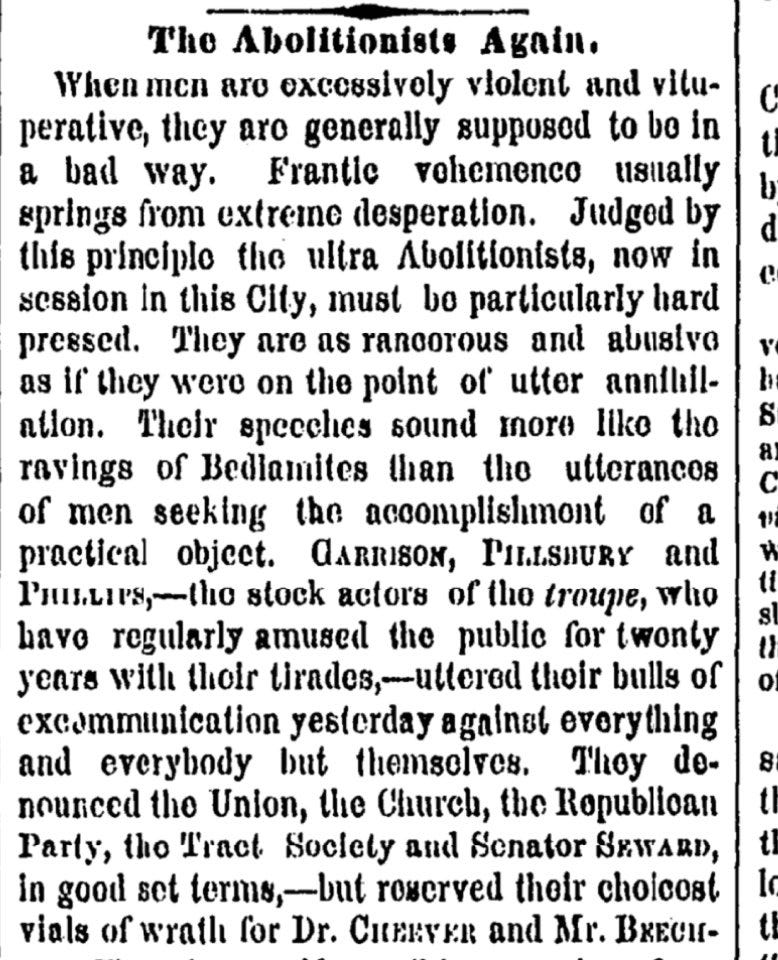

NYTimes, 1860: "[The abolitionists] are as rancorous and abusive as if they were on the point of utter annihilation. Their speeches sound more like the ravings of Bedlamites than the utterances of men seeking the accomplishment of a practical object."

Slavery’s unique horror and the politics it produced have no modern equal, and the Republican Party of the 1850s was forged for a singular purpose: to resist and ultimately destroy the “Slave Power.” And today’s Democratic Party lacks a comparable unifying moral and ideological project. What carries over is the strategic problem that confronted the new Republicans: consolidate power first in safe seats or stretch into contested terrain? How do radicals, moderates, and conservatives best divide labor inside a big‑tent, two-party system—with what conflicts and in what sequence?

The electoral map of the new party—and the strategic choices

Some context: the 1850s Republican coalition fused ex‑Whigs (a collapsing national party that had tried to sidestep slavery), anti‑slavery Democrats (a minority rebelling against Southern leadership), Free Soilers (a short‑lived movement devoted to barring slavery from western territories), and a smaller band of abolitionists committed to immediate emancipation.

Political scientist Daniel DiSalvo’s framework helps: factions are “‘engines of change,’ the prime movers in American politics,” a level “between” parties and lone politicians that act as “‘conveyor belts of ideas.’” They are “coordinated network[s] that tie together elites from a variety of institutions,” capable of moving “the whole party along a left‑right spectrum.”

Historian Hans Trefousse sketches the GOP’s factions as “radicals, moderates, and conservatives” who “differed in both ends and means”—with radicals pressing the attack, moderates forming the majority, and conservatives hoping to turn back the clock.

They broadly agreed to stop slavery’s expansion (“containment”), while they fought over scale and pace (radicals), coalition (moderates), and tone (conservatives). For radicals, “‘No compromise!’ was their motto—‘not even with friends if it involves the sacrifice of principle’,” a cohort “of former Free‑Soilers and other determined antislavery politicians” who refused “to recede in any way” from keeping slavery from spreading.

Crucially, where each wing lived shaped how it talked. Historian Eric Foner locates the Republican center of gravity in the Yankee villages of central and western New York, and those of Michigan, Wisconsin, and the northern counties of Ohio with echoes in northern Illinois and rural New England. Places where abolitionist sentiment ran so deep that bold antislavery positions posed no electoral risk.

“Urban political leaders, many of whose constituents were either [white] immigrants,” worried that letting “New England abolitionists” define the brand would be “political poison.” In short: abolitionist‑leaning safe seats became foundries; white immigrant‑heavy and “lower North” swing seats demanded different rhetoric.

In the mid-19th century, the Radical Republicans were never a majority of their party, but in the right circumstances they shaped the GOP’s direction as decisively as any party faction before or since. From those safe perches, radicals set the horizon of anti-slavery politics. Historian Bruce Levine’s portrait of Thaddeus Stevens is blunt: he created public opinion and molded public sentiment” and was almost invariably out in front of public opinion…on all the great questions of the war.

Charles Sumner played a similar role in Massachusetts, indicting what he called the “Slave Oligarchy”: “It organizes the Cabinet, directs the Army and Navy, controls the Treasury and the Post‑Office …holds the keys to every office, from President down to postmaster...Our first political duty, therefore, is to oppose this Oligarchy…Prostrate the Slave Oligarchy, and Liberty will become the universal law of all the national Territories.”

Moderates and conservatives aimed at different voters—especially in the swingier “lower North.” Foner is direct about their approach: parties there reorganized around less polarizing banners and trimmed sails to compete for former Democrats; several states even adopted “People’s Party” labels to mute “New England abolitionist” associations. Republicans tailored the message to the free‑labor common sense of swing constituencies—1850s shorthand for an economy in which ordinary people could work, save, and own, as opposed to a slave system that fixed status at birth and depressed wages and dignity.

In lower-North battlegrounds like Illinois, Democrats worked to make even a Republican moderate sound like an abolitionist firebrand. The Illinois State Register blasted Lincoln’s argument to restrict slavery as “black abolitionist propaganda,” insisting his speech “has as dark a hue as that of Garrison or Fred Douglass.” Stephen A. Douglas hammered the linkage on the stump, peddling a rumor that “one of Fred. Douglass’ kinsmen…is now traveling in this part of the State making speeches for his friend Lincoln as the champion of black men,” and at Charleston claiming he had found Lincoln’s ally “in the person of Fred. Douglass, THE NEGRO.”

Lincoln’s opponent pressed the point further by associating Lincoln with several radicals and abolitionists: “Did Lovejoy, or Lloyd Garrison, or Wendell Phillips, or Fred. Douglass, ever take higher abolition grounds than that?” The goal was to brand the GOP in swing counties as synonymous with Black equality and abolitionist “extremism,” attempting to impose a political tax on Republican moderates that radicals in safe New England seats didn’t have to pay.

Policy and ideology tended to follow demographics and geography. James Oakes sums up the party’s containment strategy: “The Republican Party called upon the ‘national forces of freedom’ to hem slavery in, to confine it, to ‘localize’ it, and to surround it.” Hemmed in, slavery would be “on the path to ‘ultimate extinction.’ Like a scorpion girt by fire…slavery would inevitably sting itself to death.” Republicans as a big-tent party “were not proposing to abolish slavery in the states”; the aim was to strip national “special protection” and turn federal levers—territories, D.C., commerce—toward freedom.

Coalition math—and the near‑misses

Because partisan electoral math can be brutal, the GOP repeatedly slammed into the dilemma any junior partner recognizes: how far can you stretch without dissolving what you are? After Lincoln’s election—but before the Civil War—Republican moderate leaders across the spectrum “urged one another to keep quiet and even to assume a conciliatory posture,” stressing that they “would never directly abolish slavery in the states where slavery already existed,” in hopes of “limit[ing] the scope of secession.”

Conservatives sometimes turned that caution into a cudgel against the left flank; one familiar complaint, Foner notes, was that “the doctrinaire morality of the Sumners…[was] doing the Republican party more harm than good.”

But radicals, for their part, saw excessive accomodation as a hollowing‑out risk. In 1860, conservative Republicans floated Edward Bates of Missouri to broaden the map. Foner again: “the radicals made it clear that they would bolt the party if Bates were chosen. While they did not insist on one of their own, they ‘demanded that a Republican candidate’ be chosen, one who had supported Frémont in 1856.” Bates’s nativism, reflecting many of his own voters views, made him “anathema to German‑born Republicans” like Carl Schurz—stretch one way, risk losing another constituency.

How movements anchor within parties

Why fight inside the party at all? As Daniel Schlozman argues, in American politics movements change the country when they become “anchoring groups” inside parties that actually hold power. Parties control the levers of the state; factions that anchor within them can trade votes, money, networks, ideas, and moral urgency for influence over the party’s agenda.

But anchoring comes with a price: you inherit all the coalition’s internal friction. In the early months of the Civil War, New York Republican Alexander Diven made the classic moderate’s case against letting the radical flank set a distinct party program: “I am not willing to open the floodgates of discussion upon all these questions…Let us not have a policy of our own, but unite with the thousands…of War Democrats; for if we have a policy of our own, we shall divide the Union cause.” The very structure that gives an anchored movement access to governing also forces it to navigate — and often defer to — the broader coalition’s electoral and strategic anxieties.

Radicals pushed back just as hard from the other side. Sumner, exasperated in 1862: “I am pained inexpressibly at the delay which gives to our marvelous advantages the aspect of failure…How vain to have the power of a God, and not to use it wisely!”

Governing re-sorted the coalition fast. The first Radical program—Black suffrage, land redistribution, and overturning Johnson’s Southern governments—hit a wall. “No party, however strong, could stand a year on this platform,” one Republican paper warned. Leadership soon shifted from the Radicals to moderate Republicans, who ultimately steered Reconstruction onto a narrower path and dismantled much of its transformative agenda.

Moderates thought the country had “suffered too much from ultra-ists and wranglers,” aimed to judge Southern whites by “present loyal purpose” rather than “past disloyalty,” and wanted Reconstruction settled quickly so the nation could turn to economic growth. “If ‘Sumner and Stevens, and a few other such men do not embroil us with the President,’” Senator William P. Fessenden wrote, “matters can be satisfactorily arranged—satisfactorily, I mean, to the great bulk of Union men throughout the States.”

That’s the junior-partner burden in a sentence: in a broad coalition, they carry the ideology but credit diffuses and blame concentrates. A bloc can move the platform, message, and the law—and still watch others set the timetable.

Why does any of this matter today?

Sequence and focus matter. If there’s one lesson the 1850s offer about safe seat primaries vs purple and red general elections, it’s sequencing. First consolidate a coherent bloc and infrastructure of voters, donors, and networks of leaders; then negotiate from strength to make national majorities possible and grounded in an ideological vision. That’s how abolitionist insurgency created the political space for a moderate Republican like Lincoln to take the presidency four years after its first national run. And when the test came, the party as a whole held its line. Foner’s verdict on the secession crisis: “While the conservatives would sacrifice anti-slavery to save the Union, and the radicals would endanger the Union to attack slavery, the moderates, with Lincoln at their head, refused to abandon either of their twin goals: free soil and the Union”

From its founding in the 1850s, the Republican Party was a coalition at war with itself over how to turn antislavery conviction into national majorities. The nominating contests of 1856, 1860, and 1864 each revealed the push and pull between radicals, moderates, and conservatives. In 1856, radicals arrived at the first convention expecting compromise, only to win a platform denouncing Southern slavery and Mormon polygamy as the “twin relics of barbarism” and calling for slavery’s “complete denationalization,” while moderates put forward John C. Frémont to test it nationally.

In 1860, moderate William Seward’s approach was embraced but he was seen as too personally polarizing; Abraham Lincoln emerged as the swing-state candidate who could carry certain parts of a radical platform without the radical’s baggage.

By 1864, many Radicals were frustrated with Lincoln’s cautious pace on emancipation and Reconstruction, and some seriously considered mounting a challenge to his renomination. Rather than risk a split in the middle of the war, Lincoln absorbed portions of their agenda—most notably accepting a party platform that called for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery.

The episode reinforced a recurring sequence in Republican politics: radicals consolidated their base and set the ideological horizon, moderates expanded the coalition to win nationally, and together they hammered the platform into clearer, bolder form. Even as the junior partner, the radicals showed they didn’t necessarily need to carry battleground states on their backs or the top of the ticket to shape the party’s governing commitments in lasting ways.

But the costs can be real: over-invest in blue strongholds and you risk moral clarity without governing power; over-invest in purple seats and you risk power without a project. The 1850s Radical Republicans addressed it by sequence—build the edge that pulls the center, then build the center that carries the edge into power and knowing when to bend and adapt to keep the tent from collapsing.

Bottom line

Much of what determines a party’s ideological direction—the selection of candidates in primaries, the protection of incumbents, the setting of strategic priorities—happens upstream, well before the general election, and often in rooms where access is far more limited. Without independent resources, a loyal and identifiable voter base, or a slate of aligned candidates, a seat at the table without power can end up more advisory than directive.

This is especially true in primary season, when party leadership tends to close ranks early in battleground seats around favored candidates and resource flows are locked in months before the public phase of the race. Historically, factions that successfully influenced a party’s direction first built their own infrastructure in safe strongholds, developed a network of aligned candidates, voters, donors, and networks of leaders and demonstrated the capacity to win and govern. Only then did their presence at the table carry real weight, because they arrived not just as participants in someone else’s strategy, but as power centers in their own right.

That’s not a one-to-one script for the present. But it is a usable past: safe-seat consolidation to set an urgent, ideological horizon; contested-seat pragmatism to assemble the majority; and intraparty struggle over speed, scope, and risk. Factions are where the devil lives in the details—they force the party’s moderates to take sides on uncomfortable questions they’d rather avoid, preferring instead to unite the coalition through negative partisanship against the other side. The NTTimes begged Radical Republicans to stop talking. They didn’t and then they governed.

The 1850s were ever-increasing gnarly political chaos, including 1860 up to the SC secession, when it becomes simply a civil war. The 1850s’ history has always reminded me too much of the breaking-apart feeling we have now.

I have to be honest, the analogies drawn in this piece are compelling but the CIVIL WAR feels a bit like the elephant in the room....

Abolitionists and radical Republicans would never have won their program (or the parts of it that they did - notably abolition, if not full reconstruction) without military defeat of the South - slave power was too entrenched, economically and politically.

If today is like the 1850s and 1860s (and it does feel more similar all the time), surely there are lessons and warnings there beyond just intra-party electoral strategy.