SNCC’s Ghosts, the Fourth Republic, and the Crisis of Liberalism

Liberalism versus nationalism, social democracy versus identity politics: the Fourth Republic’s buried quarrels and the search for a new American order.

Every republic has founding quarrels. India has Nehru, Gandhi, and Ambedkar arguing over whether the new state would be socialist, village-centered, or liberal-constitutional. Pakistan has Iqbal and Jinnah wrestling with what it means to build a Muslim homeland out of the wreckage of the Raj. South Africa has Mandela and the ANC leadership negotiating, under the gaze of the old security state and with the memory of Biko hovering over the room, what a post-apartheid constitution should guarantee and what it cannot yet touch. Across Latin America, the transitions out of military rule and the new constitutions of the 1980s and 1990s posed the same question in different accents: how far to curb markets, the generals, and the old oligarchies without igniting a counterrevolution.

In the United States, we can name three such moments without much effort. The First Republic is born from Madison, Hamilton, and the Anti-Federalists arguing over the reach of the new federal government. The Second emerges from Lincoln, Douglass, Sumner, and Stevens fighting over slavery and Reconstruction. The Third is the New Deal order of Roosevelt, Frances Perkins, Walter Reuther, and Southern barons battling over the mass-party welfare state that remade capitalism without abolishing it. Their disagreements over federal power, race, and markets still structure our politics.

What we lack is a comparable language, and an equivalent cast of founders, for the Fourth American Republic: the constitutional order created when Black Americans forced the United States to dismantle de jure apartheid and finally extend formal citizenship across the color line. Between Brown v. Board and the Voting Rights Act, the country became, on paper, a multiracial democracy layered onto the New Deal’s economic regime. Yet the people who argued most intensely about what that democracy should be are rarely treated as framers. They are remembered as “civil-rights leaders,” not as architects of a new order.

This matters because the arguments we now conduct under the heading “the crisis of liberalism” are downstream of that unfinished founding. Jerusalem Demsas reaches back to Locke and Shklar to ask what liberalism is for: how a diverse society lives together without turning politics into permanent retribution. Matthew Yglesias looks at the institutional language of contemporary anti-racism and hears an illiberal turn: groups displacing individuals, neutral rules and objectivity treated as domination, universal rights and due process treated as obstacles. My own response has been that much of what he calls “postliberal” is not an external invasion but liberalism’s own cramped, elite offspring: a professional style that promises recognition inside institutions while leaving the political economy largely intact. Those are contemporary arguments, but they are not necessarily new arguments. They are, in softened and professionalized form, the arguments that forged and divided the founding generation of the Fourth Republic.

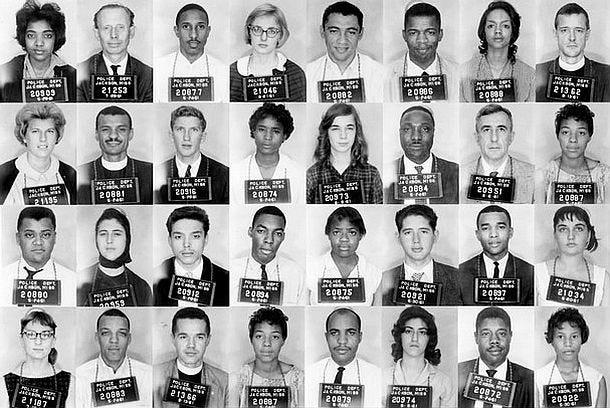

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the crucible where many of those fights were conducted. SNCC’s organizers—John Lewis, Stokely Carmichael, Bob Moses, Ella Baker, Diane Nash, Fannie Lou Hamer, James Forman—and allied figures like Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr. fought over the meaning of American liberalism, the role of racism and capitalism, and the future of the Democratic Party. Their debates, as Founding Fathers and Mothers of a new republic, set the terms of the settlement that followed. Their breakup left unresolved tensions that still shape what counts as “liberal,” what counts as “identity politics,” and the Democratic Party.

By the early twenty-first century, the Fourth Republic had produced a strange pair of truths at the same time: civil-rights law and mass incarceration, voting rights on paper and relentless voter suppression, a Black president and a widening racial wealth gap. Out of that mismatch, a new institutional common sense took shape in universities, foundations, nonprofits, and HR departments. Suspicion of “neutral” rules and an emphasis on lived experience came down from the disillusioned liberals and Black feminists who learned, the hard way, how easily “procedures” could be weaponized against them. A commitment to rights, due process, and multiracial democracy came down from radical egalitarians like Lewis and King who believed the Constitution could be made real. What did not survive intact were the social democratic programs and mass organizations that once made those ideals feel actionable.

That is the missing genealogy in today’s liberalism debate. What looks like a new clash between “liberalism” and an “identity left” is, in large part, what happens when the critique survives but the program dies. SNCC’s insistence that standpoint matters and neutrality can be a mask was forged in real encounters with white institutional power, from county courthouses to Atlantic City. Black feminism’s insistence that oppression is interlocking was forged in real encounters with male leadership and with the politics of the private sphere. When the economic horizon narrows and social movement organizational muscle withers, those critiques do not disappear. They reappear inside the institutions that remain available as culture and compliance: battles over language, representation, and the management of harm. The moral energy remains, but it gets redirected toward what those institutions can actually touch.

A founding vote at five in the morning

To see those conflicts in miniature, go back to a staff retreat in Tennessee in 1966. Around five in the morning, after hours of criticism, the room turned on John Lewis. These were people he had gone to jail with and been beaten beside. Now they accused him of clinging to an outworn theory of change and refusing to recognize how much the terrain had shifted since 1960. One participant later said the meeting felt “almost like a mob.”

Lewis mostly listened. He did not speak. When the tally was read, Stokely Carmichael was the new chair of SNCC. Lewis walked back to his room “drained, exhausted, dazed.” When he woke up later that morning he realized, “It was over.” Years later he wrote that the blow “hurt more than anything I’d ever been through,” not because he had lost a title, but because “breaks were created; wounds were opened that would never heal…It was not so much a repudiation of me as a repudiation of what we were, of what we stood for.”

What they had stood for, at least in SNCC’s earlier years, was a radical version of liberal democracy made real in places where liberal democracy had never existed.

The radical egalitarian wager

Early SNCC organizers treated citizenship as an operating problem, not a slogan. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments promised equal protection and the franchise; they set out to collect on those guarantees in counties where Black people had never been allowed to register, serve on juries, or walk into courthouses without fear. Students rode Freedom Rides into hostile towns. In McComb, Greenwood, and Selma they organized sit-ins and voter-registration drives under constant threat of eviction, job loss, or murder. They learned the routines of registrars and sheriffs and the layout of county courthouses the way more conventional politicians learn donor lists.

Under that pressure, mid-century liberal institutions moved. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. Federal examiners appeared in counties that had never allowed Black names on the rolls. Sheriffs who once ruled with impunity suddenly faced Justice Department lawyers and national television.

For Lewis and many of his comrades, this proved that the American system, however brutal, could be forced toward justice. In Black Visions, political scientist Michael Dawson calls one long tradition in Black political thought radical egalitarianism: a searing critique of racism coupled to an appeal for America to live up to its best ideals, backed by a strong central state, and married to the belief that capitalism is deeply flawed but politically reformable. Alliances with “all people of good will” are not sentimental; they are strategic. This is the tradition that makes Frederick Douglass’s denunciations compatible with constitutional argument and makes King’s “promissory note” speech an act of both indictment and belonging.

Bayard Rustin tried to turn this wager into policy. In “From Protest to Politics” and in the Freedom Budget that followed, he argued that the movement had to move from forcing access to forcing redistribution: full employment, strong unions, and a generous welfare state. In his vision, the Fourth Republic would complete what the Third—the New Deal order—had done only halfway: extend social democracy across the color line and make the welfare state as real in Black communities as it had been in white ones. SNCC in its early phase was the militant wing of that project. It was not trying to overthrow liberalism; it was trying to make liberalism true.

Atlantic City and the discovery of limits

Clayborne Carson’s history In Struggle shows how quickly the evidence began to complicate that faith. Freedom Summer had already revealed how slow and partial federal protection could be. Then the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party—an integrated slate of maids and sharecroppers elected in open precinct meetings across the state—traveled to the 1964 Democratic convention in Atlantic City to demand the seats held by Mississippi’s all-white regular delegation. Fannie Lou Hamer’s televised testimony about being beaten nearly to death in a Winona jail, ending with “Is this America?”, produced a flood of telegrams backing the MFDP.

President Johnson and party leaders offered a “compromise”: the segregationist delegation would keep its seats; the MFDP would receive two at-large, non-voting chairs. Rustin and King, under intense White House pressure and convinced that a Goldwater victory would be catastrophic, urged acceptance. Moses, Hamer, and most of SNCC’s Mississippi staff refused. They believed they had forced the Democratic Party to choose between the old order and the new, and had watched it choose the men who had built Jim Crow.

Dawson gives a name to the outlook that takes shape after experiences like this: disillusioned liberalism. It still values egalitarian democratic ideals, but sees the United States as fundamentally racist. It treats segregation or autonomy not as a final goal but as a tactical stage in a long struggle. It sees capitalism and white institutional power as part of the problem, not merely the stage on which the problem plays out. Moral suasion and scientific evidence are not enough to mobilize a white majority over time. Under those conditions, the emphasis shifts toward building independent Black political and economic power as the precondition for equality.

By the late 1930s W. E. B. Du Bois had reached a similar conclusion. King, by 1967, began speaking in a comparable register. In Where Do We Go from Here? he told the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that “racism still occupies the throne of our nation,” and launched the Poor People’s Campaign with the goal of “restructuring the whole of American society.” After Atlantic City, many SNCC organizers, especially in Mississippi and Alabama, began to see the Democratic Party and the liberal state through the same lens.

This is the first crucial point for the contemporary liberalism debate: the suspicion of “neutrality” and the insistence that institutions have interests is not a late, academic fashion. It is a conclusion earned in a fight where the rules of the game claimed to be democratic and then proved to have a trapdoor.

Carmichael’s turn and the nationalist answer

Stokely Carmichael’s political journey passes through disillusioned liberalism but does not end there. He entered the movement as a believer in interracial democracy, joined the Freedom Rides, and endured fifty-three days in Parchman Penitentiary. In McComb and Greenwood he watched federal marshals arrive after the worst violence and depart before the danger had passed. In Lowndes County he helped build the Lowndes County Freedom Organization—the original Black Panther party—so that Black farmers could vote for a party of their own rather than for Dixiecrats or a national party that treated them as an embarrassment. That experiment fits Dawson’s description of disillusioned liberalism: equality pursued through building Black power within legal and electoral frameworks, while letting go of the hope that white majorities will be persuaded by appeals to conscience alone.

By 1966, however, Carmichael was already moving further. Dawson lists him, along with Garvey and Malcolm X, as a leading exponent of Black nationalism. Nationalists, in Dawson’s definition, distrust alliances with outsiders and argue that unity and power must be built inside the Black community before coalitions are even contemplated. Some strands are open to alliances with other oppressed peoples; others treat most outside ideologies, liberalism included, as tools of white domination. Carmichael’s admonition that white activists should “organize your own,” his embrace of pan-African politics, and his later life as Kwame Ture belong to that current. Disillusioned liberalism is often a transitional position in Dawson’s map; activists who remain committed to struggle but lose faith in liberal institutions frequently move on to nationalism or Marxism.

Seen this way, Carmichael’s nationalism is not a repudiation of SNCC’s early victories. It is a different answer to the question those victories posed: what comes after the legal architecture of Jim Crow has been dismantled but the economic and carceral structures remain? If the Fourth Republic was content with equal citizenship on paper while leaving the underlying distribution of land, jobs, and police power largely intact, nationalism was one proposal for a different constitution.

King, Rustin, and the attempt at synthesis

If Carmichael came to embody the nationalist answer to the Fourth Republic’s problems, Rustin and King spent their last years trying to hold a different line. Both began squarely in the radical egalitarian camp. Both were forced, slowly and painfully, toward Du Bois’s darker conclusion that racism and capitalism were woven deep into the fabric of the state. Dawson reads them as figures who move from radical egalitarianism toward disillusioned liberalism without abandoning either.

Rustin’s story captures the tension. A former communist and lifelong socialist, a Quaker pacifist who became the movement’s master tactician, he understood that protest had to fit the underlying configuration of power. His March on Washington was not a generic moral pageant; it was designed for a moment when civil-rights legislation had broad support but was being stalled by preference intensity, congressional norms, and the fact that many Black Americans still could not vote. After the mid-1960s victories, Rustin argued that protest could no longer be the movement’s center of gravity. The new problems were “normal” ones—jobs, wages, schools, housing—and they demanded “revolutionary” but race-neutral solutions: full employment, public works, expanded social insurance. The Freedom Budget tried to fuse civil rights and labor demands into one social-democratic program.

At the same time, Rustin’s tactical commitments bound him tightly to coalition politics inside the Democratic Party. His willingness to accept Johnson’s terms at Atlantic City, his reluctance to break with the administration over Vietnam, and his later alliances on Cold War and Israel policy showed how far he was willing to bend to keep a coalition intact.

King’s trajectory runs alongside Rustin’s but begins from a different moral place. The King of 1963 is the purest voice of radical egalitarian liberalism. By 1967 he sounds like a democratic socialist shaped by disillusion: condemning “the triple evils of racism, economic exploitation, and militarism,” calling for guaranteed income and a “radical redistribution of economic and political power,” and turning openly against Vietnam even as advisers warned it would cost him his standing with much of the liberal and labor establishment. Yet he refused to cast his project as a break with America. The Poor People’s Campaign was designed to force the nation to be true to what it claimed on paper to working class Americans of all backgrounds.

Together, King and Rustin were trying to write a constitution for the Fourth Republic that would bind civil rights to social democratic economic transformation and connect Black freedom at home to a critique of American power abroad. They did not live to see whether that synthesis could survive.

Black feminists added another set of questions that neither liberal nor socialist nor nationalist men had adequately confronted. Dawson treats Black feminism as its own ideological tradition rather than an offshoot of anyone else’s. Its thinkers argued that the standard liberal language of autonomous individuals and public/private separation could not capture lives structured simultaneously by race, gender, class, and sexuality. They criticized the sexism of both integrationist and Black Power leadership, insisting that any future republic would have to remake the household, the clinic, and the bedroom as well as the courthouse and the ballot box. Their insistence that systems of oppression are interlocking would become one of the most durable legacies of the era.

SNCC and Social Democracy

You can see what SNCC was up against more clearly if you set it next to the stories about social democracy and liberalism elsewhere. Social democracy comes out of a blunt trade: mass workers’ parties give up on overthrowing capitalism and instead commit to taxing, regulating, and bargaining with it. Labor gets something real in return — a party of its own to sit across from both liberals and conservatives, a welfare state, a say over investment and redistribution. Capital keeps the basic structure of the market.

As Davis argues in Prisoners of the American Dream, that bargain never really happened in the United States. There was no mass labor party. The New Deal coalition was stitched together inside a racially divided Democratic Party; the CIO’s insurgency was contained; dissident currents were folded back into what Davis calls a “one-and-a-half-party system” designed to absorb and blunt them. Instead of European social democracy, the United States produced a hybrid progressive liberalism that tried to yoke together strong individual rights, a market economy, and suspicion of concentrated state power. The result was a liberal order that could build a welfare state for some, but that treated both socialism and racial equality as threats to its foundations.

SNCC’s project sits right at the collision point of all this. Its organizers were trying to force social-democratic outcomes — jobs, schools, welfare, real political power — out of a liberal order that had never had a social-democratic party, inside a two-party system whose majorities had historically been built on racial compromise. In Western Europe, the drama describes revolves around whether mass socialist parties will stay revolutionary or settle into managing a capitalist welfare state; race and empire are present, but often kept offstage. In the United States, race and the party system are onstage from the first minute.

When Lewis and Rustin try to imagine a Black-inflected New Deal inside that structure, they run straight into those limits: a liberalism that can live with some regulation and welfare, but that flinches when demands endanger its racial bargains or its faith in the market. When Jesse Jackson tests the idea of a multiracial Rainbow coalition, he isn’t just having a family argument with white liberals. He is discovering how hard it is to do European-style social democracy in a country where racism, liberalism, capitalism, and the two-party system are fused. The landscape we are arguing over now grows out of that failure: liberal institutions that still talk about rights and rules but rest on a much weaker egalitarian base, and a style of identity politics that remembers all of SNCC’s critique of liberalism and almost none of its plan for what to do with power once you actually have it.

Jackson’s lost fork in the road

The institutional settlement that followed SNCC’s debates never fully matched what SNCC’s founders imagined. SNCC collapsed under state repression and internal conflict; the Black Panthers followed; labor unions shrank. On paper, the Democratic Party changed a great deal. It adopted civil- and voting-rights laws, opened its rules, and became the main home of Black voters. Black elected officials and staff entered in far greater numbers. But this new Black presence sat inside a party that never embraced the social-democratic program Rustin and King had sketched.

Black politics inside the party moved toward what Dawson calls “deracialized” liberalism and brokerage. Black mayors and legislators took office in cities hollowed out by deindustrialization and white flight, tasked with managing austerity and policing rather than building new welfare states. Black officials who had once been movement organizers became mediators between poor Black neighborhoods and largely white corporate and state power, translating demands upward and defending scarce budgets downward. The promise of the New Deal’s Third Republic, finally opened to Black participation in the Fourth, arrived just as its economic foundations were being pulled apart. Reaganism layered renewed market orthodoxy and “law and order” politics on top of this unfinished racial settlement. One could argue that the Reagan Revolution amounted to a kind of Fifth Republic.

Jesse Jackson’s presidential runs in 1984 and 1988 were the closest the Fourth Republic came to reversing that trajectory. Jackson tried to fuse the lessons of SNCC, King, and Rustin with a new base: Black voters, the remnants of industrial unions, public-sector workers, feminists, farmers, peace activists, and the growing Latino electorate. The Rainbow Coalition offered a second-Reconstruction ambition in a Reagan era. It tested whether a left politics of jobs and peace could be built on a multiracial coalition of the most vulnerable.

The reaction was instructive. According to Mike Davis, much of the trade-union bureaucracy and much of the newly ascendant Black reform leadership closed ranks against the Rainbow. Top AFL-CIO officials, already retreating from full-employment politics, feared Jackson’s open-ended demands and clung to Mondale. Many Black mayors and local machines, dependent on federal grants and DNC relationships, hedged or stayed loyal to the establishment. On the white left, the backlash sometimes exposed a kind of neo-racism: patronizing reactions that revealed how deeply “white” the self-concept of many left-liberals had become, and how unwilling they were to accept even modest nonwhite leadership. After Mondale’s defeat, party leaders and liberal commentators scapegoated “special interests,” often meaning Black movements and the Rainbow.

Jackson’s campaigns are therefore both culmination and tombstone. They represent the last serious attempt to realize the Rustin–King vision of race-conscious social democracy inside the Democratic Party, and they mark the moment when that possibility was effectively buried. The reform space inside the party narrowed; the neoliberal succession accelerated; Black Democrats were asked to supply loyalty without setting the agenda.

From SNCC to the henhouse

By the early twenty-first century, the country had civil-rights laws and mass incarceration, voting rights on paper and rampant voter suppression, a Black president and a widening racial wealth gap. In universities, foundations, nonprofits, and HR departments, a hybrid sensibility took shape. Suspicion of “neutral” rules and an emphasis on lived experience descended from disillusioned liberalism and Black feminism. A commitment to rights and procedural fairness descended from radical egalitarianism. What dropped out were the robust social-democratic programs and the insurgent mass organizations that had once given those ideas force.

This is the missing genealogy in today’s liberalism debate. What Yglesias calls an “identity left,” and what I described as henhouse liberalism, is not an academic conspiracy or a social-media glitch. It is what happens when the critique survives but the program withers. SNCC’s insistence that standpoint matters and neutrality can be a mask was forged in real encounters with white institutional power. Black feminism’s insistence that oppression is interlocking was forged in real encounters with male leadership and the politics of the private sphere. When the economic and organizational horizon collapses, those critiques reappear inside professional institutions as culture and compliance: disputes over language, representation, and the management of harm. The moral energy remains, but it is redirected toward what these institutions can actually touch.

Rustin’s wager, at his best, was that you could confront both the limits of Black nationalism and the complacency of white liberalism with the same instrument: a genuinely ambitious, genuinely multiracial social democracy. Against nationalists, he argued that separatism and symbolic militancy could not touch unemployment, wage inequality, or failing schools, and that traumatizing white people with sharper rhetoric is a no-win strategy if you do not also build governing coalitions. Against white moderates, he insisted that civil-rights statutes and representation were not enough; a republic that leaves labor markets, housing, and welfare to the tender mercies of capital will keep sorting Black people to the bottom. The Black freedom struggle would live or die on whether it could win majoritarian support for full employment, public works, universal benefits, and a state strong enough to discipline both employers and police.

If there is a path to a new American republic beyond the Reagan era, it almost certainly runs through that same radical egalitarianism—reworked for a post-industrial, multiracial, feminist, climate-constrained society. Versions of that kind of social, political, and institutional upheaval have already played out across much of Latin America (Brazil, Bolivia, Mexico, etc); the question is whether the United States can finally attempt its own.

It would have to say to identity-first currents that power rooted only in cultural institutions and representational wins will always be fragile if the political economy stays intact. It would also have to say to liberals that a politics organized around norms, procedures, and DEI statements will not survive another half-century of unequal wages, unaffordable housing, crumbling public goods, and periodic police uprisings.

A serious Fifth Republic would treat SNCC’s arguments as lessons, not scripture. It would hear today’s identity-driven politics and newer strains of Black pessimism as alarm bells — signs of what happens when liberalism is asked to carry more and more of the moral weight without ever changing who has money, security, or a say. And it would pick up the choice Rustin and Jackson thought was still open: whether American liberalism will remain the management philosophy of an unequal order, or become the framework for a genuinely democratic redistribution of power.

Seen this way, the arguments over contemporary liberalism we are circling around are less an abstract philosophical dispute than the afterlife of an unfinished founding of a new republic. Demsas wants a liberalism that can still answer how a plural society lives together without becoming mere defense of a fraying status quo. Yglesias wants to defend individual rights and neutral, universal rules against a politics that treats group position as morally decisive. I have argued that elite identity politics is what liberal institutions produce when they absorb civil-rights symbolism and personnel while abandoning the social-democratic ambition that once gave those fights a material horizon.

SNCC’s breakup, and the defeats that followed, help explain why these impulses now live side by side inside American liberalism and so often talk past one another. The radical egalitarians were right that without a strong, interventionist state and some real social democratic horizon, there isn’t much of a floor under anyone’s life. The disillusioned liberals were right that, without independent power pushing from the outside, law and politics slide quickly into pageantry and symbolism. Black nationalists were right that dignity demands some measure of autonomy and control over your own institutions, and wrong to imagine that autonomy by itself could undo deeper economic and political subordination. Black feminists were right that a freedom that stops at the courthouse door and never reaches the household, the clinic, or the body is not really freedom at all.

What didn’t fully come together was the hard work of stitching those insights into a shared project and winning enough to make it durable. Instead, we inherit them as fragments: a reflex to appeal to rights, a reflex to distrust rules, a reflex to insist on autonomy, a reflex to call out “interlocking” harms. They flare up in different combinations whenever liberalism comes under strain. That’s another way of saying we are still living inside the Fourth Republic’s unresolved argument — and that when we talk about what liberalism is or isn’t today, we are, whether we admit it or not, still arguing with SNCC’s ghosts.