The 2028 “Ideas Primary” Probably Won’t Be About Ideas

It will be about theories of power...and vibes.

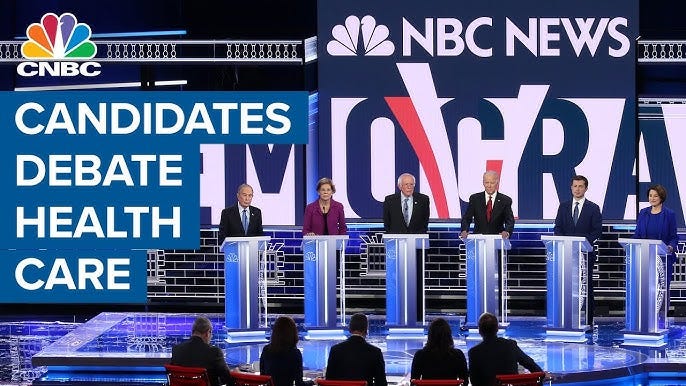

In 2020, Democrats really did have what people called an “ideas primary.” The fights were about policy design: Medicare for All versus a public option, free college versus debt relief, wealth taxes, multiple versions of a Green New Deal. The underlying assumption was still very Obama-era: pick the right blueprint, win enough seats, and the system will more or less let you implement it.

By now, though, most Americans don’t buy that premise. Majorities tell pollsters the political system is broken, rigged, and doesn’t work for them. The Democratic brand, in particular, has become “overpromise and underdeliver”: big rhetoric about climate, health care, wages, and housing followed by disappointing or invisible results. The “abundance” school of politics — clear procedural and bureaucratic veto-points to build more housing, more clean energy, more infrastructure — is one answer to that frustration, and I’m sympathetic to many parts of it. But even abundance can’t magic away minority rule in the Senate, aggressive gerrymandering in the House, a far-right Supreme Court, or the question of how aggressively a president is willing to use executive power.

By 2028, almost nobody who shapes the presidential conversation will believe that “good plans + 51 votes = change” story anymore. The editors, bookers, pollsters, and strategists who define what “the debate” is just watched a Democratic administration win, create task forces to write a big agenda on paper, and then see Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema, and a conservative Court carve the 2020 ideas primary down to something much smaller, or nothing at all. Inside that world, the working assumption now is: anything ambitious will probably die in the Senate or in court.

That means the next primary will be less about what Democrats want to do and more about how they think power works. The real dividing line in media coverage won’t be single-payer versus public option; it will be competing theories of power: What’s actually blocking change? Which levers are you willing to pull? How hard are you willing to push against the rules of the game? Everything else — the culture-war skirmishes and the electability panic — will sit on top of that.

I’m describing that dynamic, not endorsing it. In a healthier party, you’d want exactly the kind of real argument over economic and social policy we saw when Warren, Sanders, and Buttigieg laid out competing blueprints. But the lessons the system took from 2020 cut the other way. The candidate with the thinnest policy offering—Joe Biden—won the primary. The media got burned for treating white papers as the main event, and then watched Manchin, Sinema, and the Court shred most of those ideas anyway. So the incentives now point toward covering personality, vibes, and “who can actually wield power,” not a direct replay of the Medicare-for-All seminar.

One obvious theory of power is what you might call maximalist reformism, and Gavin Newsom is the clearest early sketch. In this version, he doesn’t just talk about democracy reform; he uses California as Exhibit A. He leans on his own state to stop unilaterally disarming on House maps, openly embraces a partisan gerrymander as payback for what Republicans have already done in Florida and Ohio, and cuts an ad with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez spelling out the case for using every ounce of blue-state power.

Newsom has a structural advantage in telling that story: he’s a governor. Governors don’t live in the world of Twitter arguments; they live in a world where wildfires, power rates, and housing starts either get handled or not. A properly maximalist governor would push their state as a demo project — stop unilateral disarmament on gerrymandering, expand voting access and public financing — and say: this is what we’d do nationally if we had the votes.

A second theory of power is the managerial presidency: promise to run the existing system more competently, cut a few bipartisan deals, and trust that calm, competent management will keep Trumpism in check. It’s basically the Joe Biden “return to normalcy” model — stabilize the institutions, dial down the drama, and let technocrats govern. We’ve already run that experiment once, and it did deliver some big laws. But it’s not obvious that “let’s do 2021–2024 again, but smoother” is a satisfying answer to voters who think the whole system is rigged.

A third theory of power is the familiar political-revolution model associated with Bernie Sanders: name the oligarchs, attack the billionaire class, and try to build a mass movement that can overwhelm institutional veto points. It treats American politics less as a negotiation among elites and more as a class struggle that only ends when millions of renters, debtors, and workers are organized into durable power. The open question for 2028 is whether that model can break past the ceiling it hit in 2016 and 2020, or whether it becomes one strong current inside a broader coalition rather than the organizing principle of the party.

Those are all theories of power. I’m not sure any of them are sufficient on their own. But they’ll be competing for oxygen with the two “sub-primaries” the political class finds easier to cover: the vibes primary and the electability primary.

On immigration, policing, and transgender rights, Democrats aren’t actually that far apart on substance; nobody is running on family separation or bathroom bans. The fight will mostly be about affect. Do you sound nervous when you support or criticize campus protests? Can you talk about asylum and border security in the same sentence without blowing up on Morning Joe? Do you defend trans rights in a way that also reassures those who don’t follow the issue closely?

This is where the Joe Rogan question becomes a stand-in. “Who can hang with the bros?” is a dumb shorthand for a real test: which Democrat can walk into the new populist, bro-y digital media environment and talk about social and economic issues without sounding like a scold. Coverage will focus less on detailed policy differences and more on who passes the sniff test — which is really another way of asking whose theory of power can be sold outside the MSNBC audience.

Layered on top of that is the electability primary, which already reshaped the last race. Elizabeth Warren’s campaign didn’t collapse because Democrats suddenly rejected wealth taxes; it collapsed after one New York Times/Siena poll convinced them she probably couldn’t beat Trump, and that narrative hardened. In a Trump (or Trumpist) rematch, this obsession will be even stronger. Every swing-state poll will be treated as a verdict on who is “allowed” to have ambitious ideas, and thus which theory of power is considered safe to experiment with.

Meanwhile, in the background, the material politics of corporate consolidation and people’s bills will keep grinding on. If you look at Zohran Mamdani in Queens, or Abigail Spanberger and Mikie Sherrill in very different districts, the candidates who win tend to say the same simple thing: life is too expensive because someone is gaming the system, and I’m willing to use power to stop it. Mamdani runs on rent freezes, free buses, and universal childcare. Sherrill runs on freezing electricity rates. Ideologically they’re pretty far apart; structurally they’re doing the same thing — connecting affordability to a theory of power about rigged rules and whose side you’re on.

That kind of “abundance plus affordability” politics will obviously be part of the 2028 conversation. But it’s unlikely to be a key organizing axis of the race the way Medicare for All was in 2020. Too many media and political elites now assume that anything ambitious will get filibustered into oblivion. So attention will drift toward what feels more concrete: Which theory of power seems most plausible? Which candidate can survive a Rogan interview? Who is up five points over Trump in Wisconsin?

The risk for Democrats is that these three primaries — theory of power, vibes, and electability — end up running on separate tracks. Voters don’t just need to know who sounds good on immigration or who scares Trump the most. They need a single, coherent answer to a harder question:

In a country with a bad Senate map, a hostile Court, and a furious electorate, how are you actually going to use power to make life cheaper, safer, and more democratic — and can you explain that to people who don’t already like you?

Hello, Waleed.

I think your analysis is correct, if we accept your premise that the Senate and the Supreme Court will block any real and meaningful reforms. So the obvious answer (to me, at least) is that the Dems need to aim for super majorities in Congress, along with clear policy plans (eg, single payor healthcare to compete with private insurance, government construction of affordable housing, universal pre-K through college education, etc.) and structural reforms (eg, reconstitute SCOTUS, progressive tax reform with no loopholes, strict enforcement of antitrust regulations, etc.).

Collectively, the progressive movement in the US is rich (close to $500 million to spend) and powerful. Unfortunately, it is also splintered into a thousand, narrowly focused groups. While each group has worthwhile aims, they will remain weak until they can unite under a single, overarching set of policies and goals. United, I believe they can finally carry the day and move our country forward.

There will be time, once the progressive left has control of the three branches of government, to also pursue the various worthwhile goals of each individual group. But for now, they need to unite to move our country away from the disastrous course toward which we are currently headed!

Waleed, I will go with the Political revolution