The Heterodoxy Mirage

A yearning for a bygone era that substitutes nostalgia for power.

When I used to prepare progressive candidates for interviews with The New York Times editorial board, I could almost script one part of conversation. Sooner or later, someone on the board would ask a question I imagine centrists rarely get: “What’s one part of liberal orthodoxy you disagree with?” It sounds incisive, like a test of independence. In practice it functions as a ritual of renunciation—prove your credibility by punching some hippies.

The latest repackaging of that instinct is called “heterodoxy”—the notion that if Democrats sound less progressive and a little more centrist, voters will reward them for independence. It sounds clever, but it misreads both the politics we live in and the map we run on. At heart, it’s a rebrand of an old campaign reflex: chase what polls well now, trim what doesn’t. Strategists call it message discipline—talk up the popular stuff, distance yourself from “liberal orthodoxy” on immigration, abortion, guns, policing, gender, and energy—but the exercise always ends the same way. Instead of a substantive debate about the economy, justice, or safety, the storyline becomes whether Democrats have strayed “too far left.” The posture swallows the policy and the story becomes the spectacle. The voters absorb the headline—“Democrats in disarray”—long before they hear a single argument about what the party actually stands for.

The 2024 cycle showed how little this kind of “popularist, heterodox” makeover changes perception. Joe Biden campaigned on major investments in infrastructure, lower drug prices, and new manufacturing jobs. Kamala Harris echoed that record alongside ads promising tougher law enforcement and stricter border control. None of it shifted the fundamentals. The race fixed on Biden’s age, inflation, and Harris’s failure to claim a narrative that felt like her own. In that vacuum, immigration and debates over transgender rights filled some of the space. Meanwhile, Trump carried a bundle of unpopular positions without paying for them, buoyed by a right-wing media machine that cast him as the voice of “ordinary Americans” and Democrats as condescending elites. When one side dominates the channels that tell voters who represents them, a pivot can read like surrender, not strength.

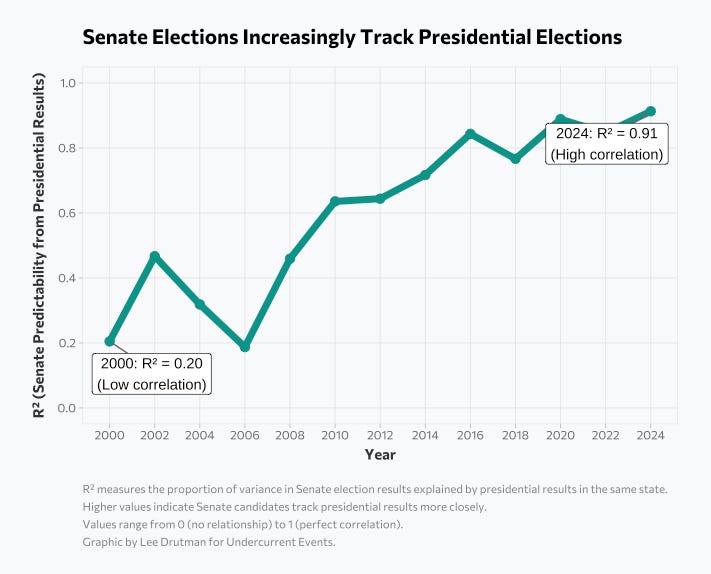

Part of the problem is temporal. Heterodoxy belongs to an earlier order—softer partisanship, stronger local news, routine ticket-splitting. That world has receded. As political scientist Lee Drutman shows, nationalization has squeezed out candidate individuality: over the past quarter century, presidential and Senate results have moved toward lockstep, and the average gap between presidential and congressional margins has collapsed by roughly eighty percent. Voters now cast ballots less for people than for parties; most races function as referendums on national identity, not local representation.

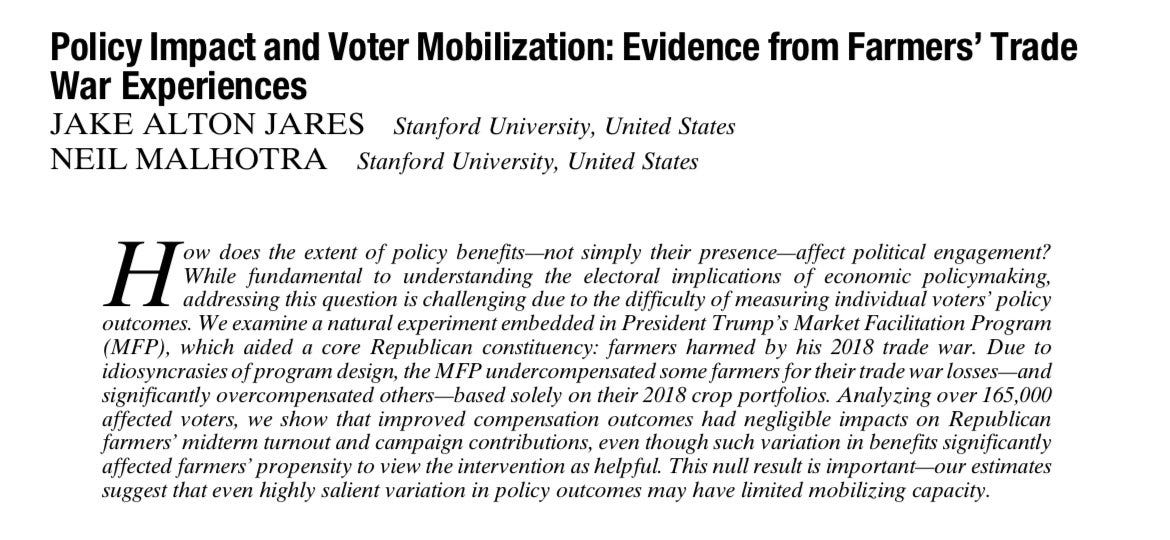

Analysts keep treating that system as if it were still primarily issue-driven and candidate-centric. G. Elliott Morris calls the fixation on heterodox positioning a strategist’s fallacy—elite instincts projected onto an electorate sorted by team loyalty. Even the related “deliverism” hope is weak as well: research on Trump’s farm subsidies during the trade war found generous benefits barely moved turnout or support among beneficiaries.

Put the evidence together and it points one way: in a nationalized, identity-heavy politics, neither moderation nor material benefits reliably move outcomes. To change outcomes, Democrats will have to think beyond messaging and confront the deeper machinery of power itself: the electoral rules and information systems that define what’s possible.

The track record of “moderation” is less a theory than a list of decisions we now regret. The last rounds of triangulation weren’t costless experiments; they produced real harms. The list includes votes for the Iraq War; curbs on abortion access; opposition to marriage equality and DREAMers; more oil and gas drilling; a moral panic over an Islamic center in Lower Manhattan; the slow strangling of the public option.

Those choices translated into lives ended or derailed, care denied, communities scapegoated, carbon locked into the future. Call it “respecting local culture” if you want; the effect is to shift the cost of flexibility onto people with the least cushion. Compromise is part of politics. Compromise also has a body count. And when it came to taking “heterodox” stands that challenged power from the other direction—on Palestinian rights, the Iraq War, expansion of health care provision, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, or the cryptocurrency boom—those weren’t the kinds of deviations that ever drew praise. We should be precise about what, in practice, these so-called “heterodox” positions entail and what trade-offs they demand from the party and its voters.

It’s also wrong to treat “heterodoxy” as some novel insight; in 2024 it was the operating system for the marquee purple and red-state races. Colin Allred campaigned in Texas with law-enforcement validators, promised to be tougher than Ted Cruz on crime and the border, and wrapped himself in sheriff badges and “secure the border” language. Sherrod Brown in Ohio sold the bipartisan border bill as “the most conservative in decades,” pointed to a fentanyl measure with Donald Trump’s signature, and defused the trans-sports hit by citing Ohio’s existing restrictions and kicking decisions to local leagues. Jon Tester in Montana leaned into distance from national Democrats, advertised pushing Biden to expand oil and gas drilling, and pitched himself as a check on his own party. All three ran the heterodox script; the results showed its ceiling. With ticket-splitting nearly gone and ballots read as choices over who controls the courts and committees, the gravitational pull of party ID prevailed. Their losses weren’t failures to moderate—they were proof moderation was already priced in, and that the map, not the message, was doing the work.

As Morris writes, you can see the pattern earlier too. Democrats lost Senate seats in Indiana, Missouri, and North Dakota in 2018—before “woke” became a catchall insult. In 2012, Ben Nelson, one of the chamber’s most conservative Democrats, retired rather than lose badly in Nebraska. The obstacle wasn’t a leftward lurch; it was nationalization and affective polarization. Rebranding the same approach as “heterodoxy” doesn’t make it new. It renames a strategy that has already hit its ceiling. We are increasingly locked inside a rigged system.

If most red- and purple-state Democrats already play defense on cultural issues, moderate Abigail Spanberger’s 2025 race in Virginia offered an alternative: engaging the culture war on new terms. The attacks were predictable—claims she would “let biological males into girls’ locker rooms and sports,” demands to endorse Governor Glenn Youngkin’s directive barring trans girls from girls’ teams. Reporters pushed for a viral yes-or-no. Spanberger reset the ground to law and governance, reminding audiences that the Fourth Circuit’s Gavin Grimm ruling governs Virginia schools and explaining the tension between shifting Title IX guidance and binding precedent. She warned that pulling federal education funds would harm classrooms and the state economy. When the questions returned, she returned to the stakes she wanted: fully funded public schools, safe and well-run campuses, and a more affordable Virginia. She won without echoing culture-war language or staging a contrived break with transgender rights advocates. The campaign refused the bait, argued from competence and process, and kept returning to everyday concerns.

Spanberger’s clarity is instructive; it doesn’t change the terrain. A few rhetorical adjustments can’t overcome malapportioned chambers, nationalized party brands, and an information environment dominated by well-funded conservative media and donors. Those forces shape how voters perceive both parties long before campaigns start.

And even the “win by sounding different” theory runs into two hard constraints. First, if heterodoxy is more than tone, it has to win the party—carry a presidential primary and redefine “Democratic” from the top down. That is a tall order. The primary electorate is disproportionately liberal and heavily Black, deeply committed to climate, union, civil, and reproductive rights. A program that trims those commitments for “electability” will be rejected by the very voters asked to bear the cost. You don’t get a new brand without first winning the contest that creates the brand. Second, the idea that progressives in blue metros should simply quiet down is pure fantasy. Those cities set tomorrow’s middle because politics and policy get tested there—paid leave, childcare, rent control, $15 minimum wage, marriage equality, taking on ICE, decarbonization standards, small-donor systems, and decarceration. As Zohran Mamdani likes to say, it’s impossible until it isn’t. Heterodox strategists rarely acknowledge—let alone explain—that blue cities as laboratories of progressivism are part of the party’s heterodoxy too.

There’s a second lesson from Spanberger that the heterodoxy camp routinely skips: persuasion lives in infrastructure. In 2024, Republicans poured tens of millions into anti-trans ads and saturated swing markets with a simple story about identity and threat. Democrats offered almost no mainstream defense—few validators, fewer ads, and little year-round content translating trans rights into universal values like autonomy, dignity, and freedom from government interference. Voters update through people they trust: local anchors, Spanish-language hosts, church circles, union stewards, youth-sports coaches, the shop owner who knows everyone on the block. If those channels hear only one side, the brand is decided long before a campaign buys its first week of ads.

Persuasion isn’t an event that happens during an election; it’s an infrastructure problem. Democrats need institutions and networks capable of steadily making the case for the world they say they want: a humane immigration system, an end to mass incarceration, a society that embraces cultural change around gender and women’s equality, a real effort to repair the harms of redlining, a safety net that works so police aren’t asked to do social work, and a credible plan for a clean-energy transition. That kind of persuasion doesn’t come from six-week ad buys. It comes from organizing, local media, civic groups, churches, unions, and the cultural work that redefines what people see as normal. When elections are the only vehicle for persuasion, Democrats are playing with half their tools. The heterodox crowd often misses this point, or treats the organizing that builds public consent as a distraction from pragmatism. But if Democrats want voters to accept big change, they have to make the case for it long before anyone walks into a voting booth.

Heterodoxy endures because it sells a comforting illusion: that a little Keir Starmer-style “hippy-punching” can substitute for rebuilding power. It offers a fantasy of politics where messaging tweaks can reverse decades of nationalization, where posture outweighs geography, and where a party that’s lost whole regions can win them back with the right tone. This is not just theoretical. In the U.K., Starmer’s sharp rebukes of progressives and insistence on a tougher immigration frame haven’t stemmed the rise of far-right Nigel Farage’s Reform UK — the populist wave he leads is now outpacing Labour in the polls and local elections.

It’s nostalgia masquerading as strategy—a yearning for a kind of gentleman’s politics that belonged to a smaller, whiter, less polarized country, where civility was treated as substance and elites could settle the boundaries of debate among themselves. That world is gone, and the longing for it has become a substitute for power. The fantasy persists because it flatters those who already hold the microphone: if only the tone were right, the public would follow. Believing that is like the NYTimes essays after John Kerry’s 2004 loss, which floated the fantasy Democrats could win majorities by moving a few million New Yorkers and Californians to South Dakota and Nebraska—an elegant way of pretending structure can be solved by behavior.

Obviously we should support candidates that fit their local ecosystems. But what I think the “heterodox” project sadly tries to do is take the aliveness of democracy out of politics. As political philosopher John Rawls once wrote, “The only justification for a conception of justice is that it can be publicly recognized as such by everyone with reason to accept it.” In plainer terms, he meant that democracy depends on citizens arguing and explaining their positions to one another. Philosopher John Dewey took an even wider view: “Democracy is more than a form of government; it is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience.” Politics, for him, wasn’t just about election math; it was also a daily practice of learning, arguing, and solving problems together. Both thinkers would likely see today’s heterodox impulse as hollowing that out—replacing persuasion with polling and treating democratic politics as something to be managed rather than lived. What remains is a thinner politics—technically strategic, but drained of the democratic argument that gives politics its soul and moral weight.

Hey, great read as always. Like bad Pilate, this 'posture' misses the point.