The Long Arc of Immigrant Power in New York

What Zohran Mamdani’s victory speech shares with the Irish ward bosses and Jewish socialists who built the city’s first immigrant-powered coalitions.

On election night, Zohran Mamdani stood before a crowd of campaign volunteers in Bronx and said something that, in another century, might have come from the steps of Tammany Hall. “We will fight for you, because we are you,” he began. “Ana minkum wa alaikum.” Then he called the roll of his coalition: Yemeni bodega owners, Mexican abuelas, Senegalese taxi drivers, Uzbek nurses, Trinidadian line cooks, Ethiopian aunties, South Asian delivery drivers. It was a moment of recognition—for communities that had long kept the city running without ever feeling like the city was theirs.

New York’s political life has always been a nexus of immigration, xenophobia, and realignment. Each new wave of arrivals has transformed the city’s parties and power structures, from the Irish Catholics who captured Tammany Hall in the late 19th century to the Jewish and Italian tenement workers who built the unions and socialist movements of the early 20th to Black and Latino transformations during the civil rights movement.

Mamdani’s rise comes amid its own modern strain of suspicion—Islamophobia, anti-immigrant politics, and the quiet bigotry that still shadows those whose faith or surnames mark them as foreign. It rhymes with the 19th-century fear of Catholic immigrants and the early-20th-century hysteria over “radical” Jews and Italians—each era finding new language for the same anxiety about belonging.

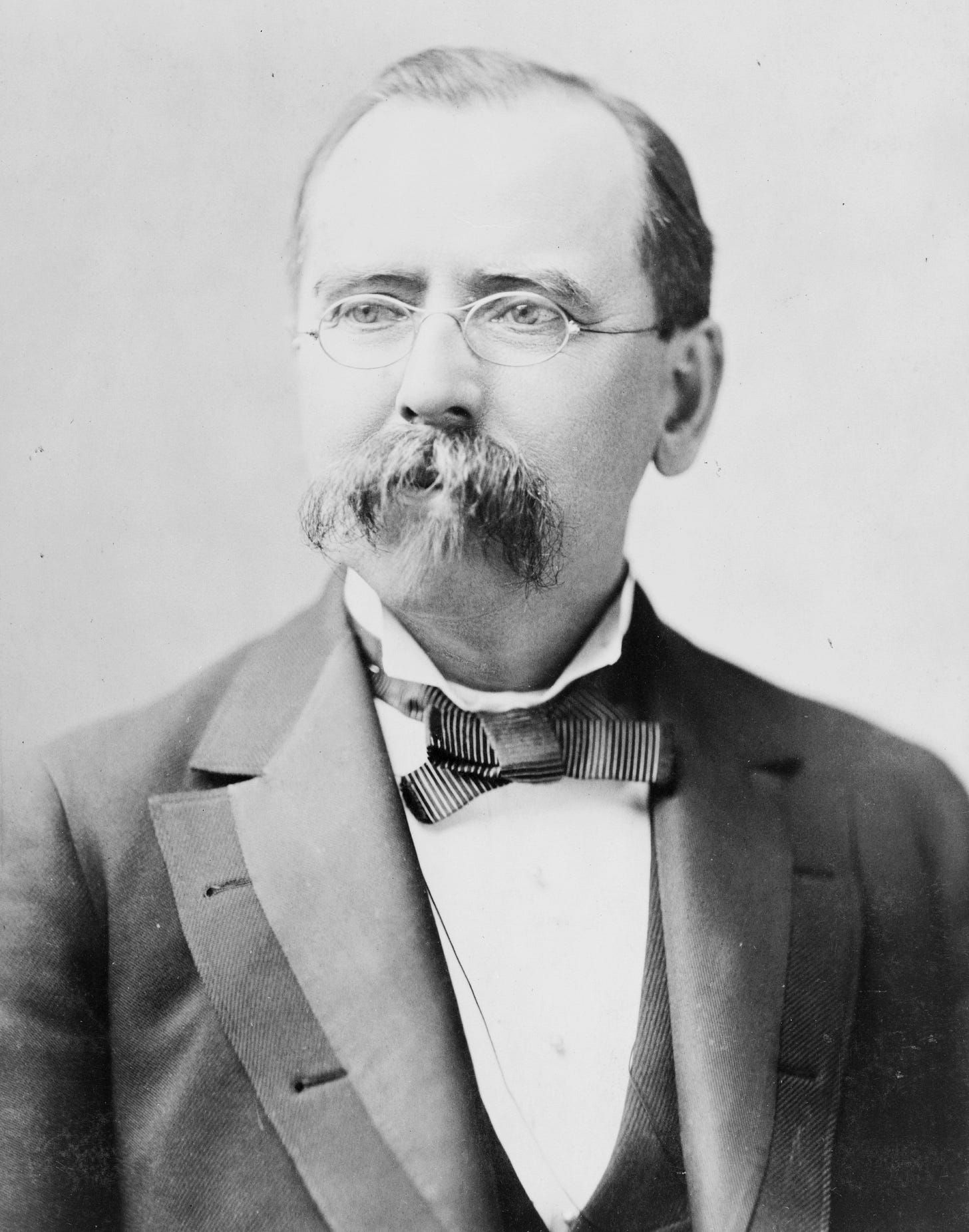

The first great breakthrough came in 1880, when William R. Grace, an Irish-born Catholic shipping magnate, became New York’s first immigrant mayor. His election was a crack in the wall of Protestant dominance that had ruled the city since its founding. Only a few decades earlier, the Know-Nothing Party had treated Catholic immigrants as a civilizational threat. Grace’s win was the city’s quiet answer: the immigrant could not only belong, but lead—a rhyme Mamdani would recognize in a new century.

For the first time, an ethnic and religious minority—despised by xenophobes as “drunkards and papists”—had seized control of City Hall. Within a decade, Tammany Hall had remade itself in Grace’s image, transforming from a genteel club into an Irish-Catholic machine that traded favors for votes and delivered something like democracy through patronage to people who’d never had it. For poor immigrants, Tammany wasn’t a story about corruption; it was proof that the system could finally see them.

By the 1920s, Irish immigrants became the political establishment, embodied by Mayor Jimmy Walker, the silk-hatted son of the machine. Walker was rakish, funny, and entirely at ease in the moral gray zone that had once scandalized elites. Under his reign, politics became a jazz-age spectacle of favors and excess. But his glamour disguised decay. The machine that had once fought for immigrants had become a gatekeeper against newer ones—Italians, Jews, and Eastern Europeans—whose sweat powered the city’s factories but who rarely saw their reflection in its politics.

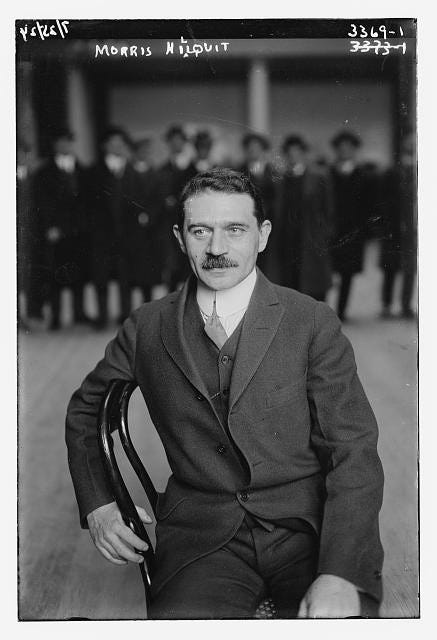

Those white ethnic newcomers found their voice in Morris Hillquit, a Jewish socialist lawyer who, in 1917, ran for mayor on a platform of rent control, union rights, and opposition to the First World War. Hillquit’s 22 percent of the vote shocked the political establishment. He didn’t win, but he proved that a tenement-based working class—Jewish seamstresses, Italian dockworkers, the radical press—could function as a political bloc. For his trouble, he and his allies were branded traitors. Five Socialist legislators from immigrant districts were expelled from the state assembly. Yet the genie was out of the bottle: class solidarity and immigrant politics had become a political movement of its own.

In 1922, during a bruising congressional campaign, Fiorello La Guardia was accused of antisemitism by a rival who assumed the charge would stick. La Guardia’s answer was pure theater and pure New York: he dictated a reply in Yiddish, the language of his accuser’s own voters, and challenged the man to debate him in it. The invitation—audacious, funny, and devastating—went unanswered. It was La Guardia at his most revealing: turning the politics of identity into a performance of fluency, using wit to remind New Yorkers that he was not an outsider looking in but a reflection of the city itself.

La Guardia’s mother was Jewish and his father an Italian Catholic who had long since drifted from faith. He grew up navigating a world of languages and neighborhoods—Italian in the kitchen, Yiddish on the street, English in the classroom. Yet despite his mother’s Jewish roots, La Guardia never publicly identified as Jewish; historians suggest he avoided doing so because he believed it would be “self-serving” and preferred his identity to be rooted in his immigrant background rather than a single faith tradition.

When La Guardia finally became mayor—after the Seabury Investigations had shredded the old party machine and the Depression had destroyed the old ethnic and political loyalties—he drew on that same fluency. He built a coalition made not only of tenement renters but of middle-class reformers, spanning Italian, Jewish, Irish, and Polish neighborhoods. Backed by the New Deal, he transformed city government from a dispenser of jobs into a provider of public assets. As fascism darkened Europe, La Guardia turned his multilingual empathy into policy—denouncing Adolf Hitler, promoting boycotts of German goods, and making City Hall a kind of civic refuge for the city’s persecuted immigrants.

Every phase of political transformation in New York City was met with a wave of bigotry. Grace faced anti-Catholic hysteria; Hillquit, the Red Scare; La Guardia, whispers that he was too foreign to be trusted. But the city’s demographic tide kept rising, and each wave of immigrants redrew the boundary between outsider and insider.

Each of these figures widened New York’s circle of belonging, though never evenly. Grace’s rise gave Irish Catholics a seat at the table but left the city’s Black residents and Caribbean migrants untouched. Hillquit’s Socialists built interracial alliances with Black labor organizers like A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, even as their broader movement still treated race as secondary to class. La Guardia, decades later, went further—appointing Black and Puerto Rican officials, investigating discrimination in Harlem, and campaigning in Spanish—but even his reform coalition operated within a segregated city. The city’s circle of belonging widened in fits and starts, stretching to include new voices even as old hierarchies tugged at its edges.

Nonetheless Mamdani’s Queens feels like it rhymes with La Guardia’s base in East Harlem and the Lower East Side—blocks of working-class renters who keep the city humming and yet pass invisibly through it.

The tenement floor now lives on a scooter and in an app: delivery riders with plastic ponchos, rideshare drivers orbiting JFK at 2 a.m., home-health aides and night-shift nurses catching the dawn train. Many are immigrants; most are tired. They’re the heirs of the garment cutters and dockhands who once packed Socialist rallies and crowded Tammany ward halls, the same stubborn coalition of people who make the city run before the city remembers their names.

In his victory speech, Mamdani named them. “To every New Yorker in Kensington and Midwood and Hunts Point, know this: this city is your city, and this democracy is yours too.”

New York has never changed by polite inheritance. Each coalition elbows its way in, and in doing so redraws the borders of “we.” Grace cracked the door; Walker swung it wide and nearly lost it; Hillquit mapped the immigrant tenement workers; La Guardia built a floor sturdy enough to stand on.

Now, in a city remade by migration once again, Mamdani’s bloc—bodega owners and nurses, young socialists, cabdrivers and the children of immigrants who bring your groceries to the fifth floor—is testing whether the city can still renew itself from the bottom up.

History’s answer tends to be yes. When New York seems sealed, someone new finds the key.

Alas, you've succumbed to a common error: Both of LaGuardia's parents were Italian born: His father was a lapsed Catholic & his mother was from a distinguished Sephardi family. He was raised as an Episcopalian & had a pivotal ally/follower in East Harlem Congressman Vito Marcantonio. Also, you miss Lower East Side born Al Smith who was NYS Governor & as Democratic candidate for President faced the winds of the anti-Catholic outcry. His gubernatorial cabinet was an incubator for what would become the New Deal. Traitor-to-his-class FDR leaned on nominally liberal Republican LaGuardia. Fast forward throw your excellent compilation: Mamdani failed to attract East Asian voters: Folks in NE Queens & Sheepshead Bay went for Cuomo. So, at this stage, there's a limit. Also, let me express concern for the physical safety of the yet to be sworn in mayor & his family.

Democracy looked different back in that day. If I remember the 1960's correctly, the police force was an Irish fief; education was Jewish; transport and social work was Black, and sanitation Italian.