Too Much Bureaucracy, Not Enough Democracy: The Battle for Abundance

What Weber, Dewey, and Reuther teach us about abundance and democratic control of bureaucracy

Americans are frustrated with a government that struggles to deliver on basic promises like affordable housing, health care, child care, public transit, and clean energy. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson argue this paralysis isn't a failure of democracy itself, but rather the stifling dominance of bureaucracy and liberalism adrift. To address this crisis, they propose abundance liberalism: a movement dedicated to removing bureaucratic barriers and rapidly increasing the supply of critical public goods. Klein and Thompson define abundance as “a political movement of supply,” focused on unleashing innovation, economic growth, and swift delivery of public needs by dismantling regulatory hurdles.

Yet, persuasive as abundance may be, many progressives see it as carrying significant risks. Kate Andrias and Alexander Hertel-Fernandez warn that abundance policies, pursued without clear attention to labor protections and economic equality, risk reinforcing inequities. If policies merely deregulate markets without safeguarding workers, they caution, abundance could inadvertently “enrich and empower concentrated economic interests,” fueling resentment and potentially destabilizing democracy. Matt Bruenig echoes these fears, arguing that the abundance framework often sidelines essential progressive priorities like economic democracy, wealth redistribution, and worker power. Without explicit commitments to these goals, abundance risks becoming just another top-down technocratic fix--one that fails to confront the deeper reasons behind America's soaring inequality.

This tension between democratic accountability and bureaucratic expertise isn’t new. Early 20th-century progressives grappled with precisely this dilemma. Historian James Kloppenberg details these debates in his book, Uncertain Victory: Social Democracy and Progressivism in European and American Thought, 1870-1920. He shows how intellectual giants like Max Weber, Walter Lippmann, Herbert Croly, and John Dewey wrestled over how democracy could survive in the face of an increasingly complex and bureaucratic society.

To Weber, democracy and bureaucracy were natural adversaries. Democracy relies on responding swiftly to the people's demands. Bureaucracy, by design, resists change. It values consistency, adherence to rules, and specialized knowledge over flexibility. In Weber’s formulation, bureaucracies inevitably create “islands of autonomous power,” effectively insulated from the will of the public they ostensibly serve.

The paradox Weber identified--the "formal rationality of administration" clashing with the "substantive rationality of popular government"--remains a central challenge today. Weber’s concern was straightforward yet deeply troubling: the modern world’s increasing complexity demands bureaucratic expertise, but bureaucracy inherently reduces democratic accountability. The more specialized government becomes, the less responsive it tends to be. He warned against a future in which elected leaders would simply rubber-stamp decisions made by technocrats.

Yet Weber also recognized the dangers of populist revolt, warning that charismatic leaders promising to dismantle bureaucratic constraints often led societies not toward greater democracy, but toward dangerous authoritarianism.

Croly and Lippmann, co-founders of The New Republic, shared many of Weber’s anxieties. Croly warned specifically that bureaucratic elites would inevitably use power “to perpetuate the system which is so beneficial to themselves.” He argued passionately that bureaucratic expertise must remain subordinate to democratic decisions--even if democracy proved slower or messier.

“No plebiscite,” Croly insisted, “can bestow authenticity upon an ostensibly democratic political system which approximates in practice to the exercise of executive omnipotence.” For Croly, democracy had a responsibility to tightly restrict bureaucracy “to providing information and executing the public will.”

Yet despite their skepticism, Croly and Lippmann themselves endorsed the creation of independent regulatory agencies insulated from direct democratic pressures. They believed deeply in scientific expertise as a way to manage the complexity of modern governance. Lippmann wrote in his influential book Drift and Mastery, “The discipline of science is the only one which gives any assurance that from the same set of facts men will come approximately to the same conclusion.”

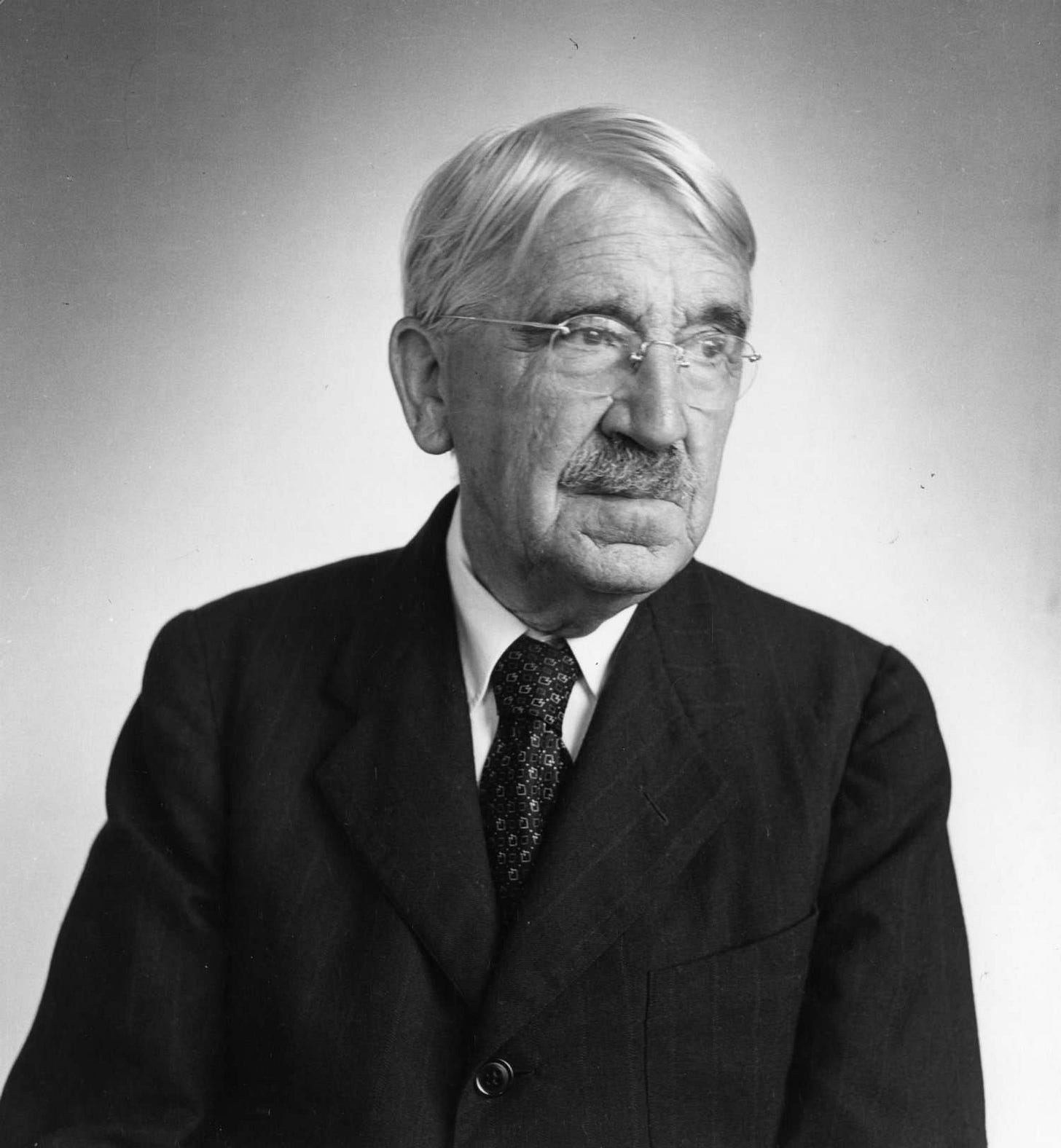

Dewey took this point further, explicitly linking democratic practice with the scientific method. “Democracy is possible only because of a change in intellectual conditions,” Dewey argued. Democracy, in his view, fundamentally implied “tools for getting at truth in detail, and day by day, as we go along.”

Yet Dewey was also clear-eyed that purely technocratic solutions would never suffice. While Lippmann worried that ordinary citizens could no longer cope with complex governance, Dewey insisted that democracy required not less engagement, but deeper and more informed participation.

He famously explained this through the analogy of a shoemaker and a customer: “The man who wears the shoe knows best that it pinches and where it pinches, even if the expert shoemaker is the best judge of how the trouble is to be remedied.” For Dewey, meaningful democratic participation was indispensable to giving bureaucracy proper direction and ensuring accountability.

This vision of democracy, grounded in worker and citizen participation, was powerfully articulated by Walter Reuther, the mid-century labor leader who led the United Auto Workers (UAW). Historian Nelson Lichtenstein, in his biography The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit, captures Reuther’s commitment to democratic ideals in an era shaped by bureaucratic expansion and unprecedented economic abundance following World War II.

Reuther understood that America faced not scarcity, but an abundance crisis--an economy so productive that it risked collapse because ordinary consumers lacked sufficient purchasing power. To address this paradox, Reuther argued for direct democratic intervention in economic planning, advocating for converting wartime factories into facilities producing affordable housing, transportation, and consumer goods. At the heart of his vision was the democratic principle that workers should directly shape economic decisions alongside government and business, not simply accept top-down bureaucratic mandates.

Reuther understood clearly that abundance was not simply a technical or bureaucratic challenge, but fundamentally a democratic one. For him, the crucial task after World War II was not only to produce more goods but to ensure that economic power was shared equitably, and that workers had a meaningful voice in shaping the economy. As Lichtenstein highlights, Reuther argued forcefully for converting wartime factories into civilian use through government-owned plants. He believed that if unions partnered with government and business in tripartite bodies, workers could ensure that productive capacity directly met social needs--housing, appliances, transportation--and distributed prosperity more evenly.

Tripartite planning was central to Reuther's vision precisely because he saw the labor movement as a vital democratic check against corporate self-interest and bureaucratic isolation. Reuther insisted that unions must participate fully in shaping industrial policy, making sure that bureaucratic institutions would reflect the experiences and needs of ordinary workers. He emphasized, as Lichtenstein documents, that democracy extended beyond the voting booth and into the economic sphere itself: "Democratic principles required economic decisions to be guided by public deliberation and shared prosperity, not merely profit maximization."

For Reuther, unions served as the democratic channel through which working people could hold both corporations and bureaucracies accountable, ensuring that abundance would strengthen rather than undermine democracy.

Today, Klein and Thompson’s critique of bureaucracy as an obstacle to abundance echoes both the anxieties of earlier progressives like Weber and Lippmann. Their famous metaphor, "Everything-Bagel liberalism," captures how excessive complexity can indeed stifle initiative and dilute democratic participation.

But as Dewey reminded us a century ago, complexity itself is not the problem. Complex conflicts--between labor and capital, environmental protection and development, racial justice and universalism, and local democracy and decisive action--are inevitable in pluralistic societies. The real challenge is balancing governance and democracy, making it deliver while being transparent, responsive, and accountable.

Without genuine democratic participation, Reuther suggested, efforts to streamline bureaucracy would merely empower a narrow elite, perpetuating a system that served itself rather than workers and the broader public, ultimately deepening the very economic inequality and democratic frustration liberals sought to overcome.

Weber’s fears about bureaucratic isolation and Croly’s warnings about administrative omnipotence remain relevant. But it is Dewey’s and Reuther’s commitment to deeper democratic participation that feels most urgently necessary today. Progressives and liberals cannot rely merely on procedural simplification or technocratic expertise. They must directly engage with democracy’s essential challenges to effectively confront the inequalities eroding our democratic foundations.

Reuther’s challenge from nearly eight decades ago was clear: abundance without democracy inevitably deepens inequality and corrodes public trust. Yet the America we inhabit today is dramatically different from Reuther’s era, when only about 5 percent of citizens had attended college, compared to roughly 40 percent now. Our economic landscape is transformed. But the core challenge remains similar. The question today, as then, is not simply how much abundance we can produce, but who controls and benefits from it.

If we're serious about making democracy work for everyone, we need to address the oldest, toughest challenge democracy has always faced: power can't remain concentrated in the hands of a few kings; it must be shared broadly, inclusively, and intentionally. Democracy thrives not by protecting privilege, but by expanding opportunity--and that requires distributing economic and political power beyond those who've hoarded it, ensuring abundance serves the many, not just the fortunate few.

TL;DR: Bureaucracy is choking democracy, and abundance liberals say "just make more stuff." But without empowering workers and communities—as Dewey and Reuther argued—we risk turning abundance into an elite project that deepens inequality instead of fixing it.

Your columns make demands on your readers, and more power to you, because they identify and inspect critically important issues surrounding the way forward, if we are to evolve in such a way as to assure the ideals of democracy. Bravo Waleed, bravo. Here the absolutely critical roles of unions and science were spelled out with such clarity that your points could not help but convince. I have read elsewhere that government, enterprise and labor are managing much of what you recommend in parts of Western Europe and all of Scandinavia. Some information about how this is succeeding in those countries would be welcome.

The future is 'less'. Human civilizations are, and have been for a long time, attacking the planet, not living within its means. Where is this in yoyur analysis?