What We Look At When We Look At a Baby

A newborn in the house, and I can’t stop watching people watch the baby.

In another life I thought I might be a medieval-studies professor; now I spend my night shift sometimes in the archives. We just had our first baby, and I keep catching myself watching people as they watch her. What used to be theory—rituals of looking, the philosophies of wonder—now shows up everywhere: in the elevator, in the living room, in the ordinary awe people bring to her small face.

We live in a country that calls itself secular, rational, optimized by dashboards and apps—and then someone has a baby and the room forgets itself. We become pilgrims. Voices drop to a hush. Strangers in the grocery aisle take on the air of deputized ushers. A small procession gathers at the stroller, each person waiting a turn as if before an icon. Offerings appear—soup, fruit, tiny socks—laid down as if to placate a household god. The baby sneezes once and grown adults cheer, as though a new revelation had arrived.

In front of a baby, looking doesn’t stay casual; it congeals into ritual. A glance grows into a gaze, and the body shifts accordingly—back stiffens, shoulders bow, breath moves in measured tides. A supplication rising from somewhere older than memory. 19th-century American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote that every picture “requires of the spectator a surrender of himself, in due proportion with the miracle.” A newborn earns that surrender without ever asking.

At 2:40 a.m., the choreography comes into focus. The phone’s white-noise playlist glows like a moon on the nightstand. Steam curls from a mug we will never drink. We bend over the bassinet and understand that what we are doing is not just watching, but entering a way of seeing that belongs to others before us.

The art historian David Morgan, writing about icons and holy images, calls this the sacred gaze—“the manner in which a way of seeing invests an image, a viewer, or an act of viewing with spiritual significance.” He meant paintings and idols, but the grammar applies here too. Wash your hands. Lower your voice. Keep watch. The body takes on the task while the mind catches up. Diaper counts, calendars, appointments, baby weights—once just noise—settle into a pattern, refracting like stained glass: data you look through while the hour steadies itself.

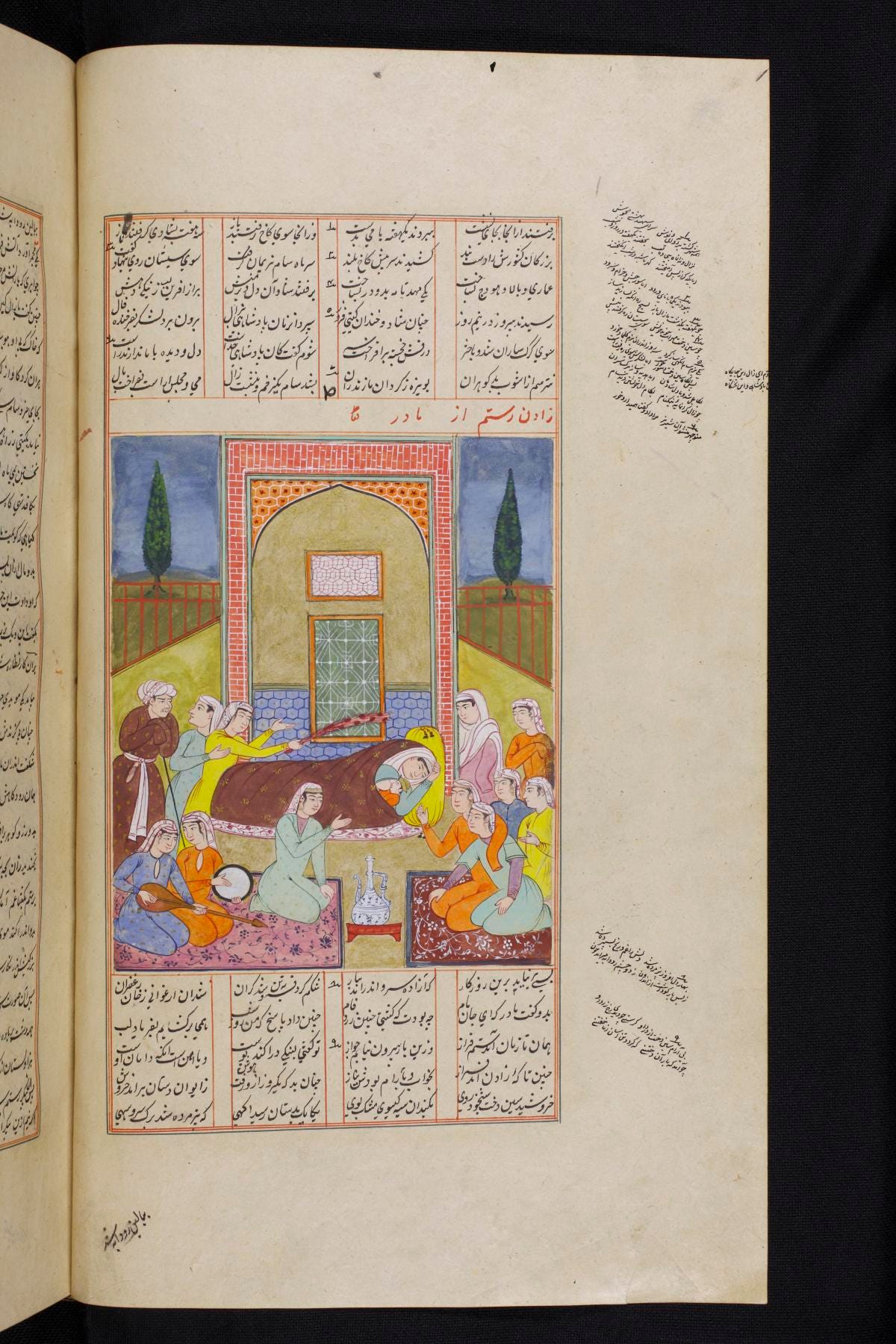

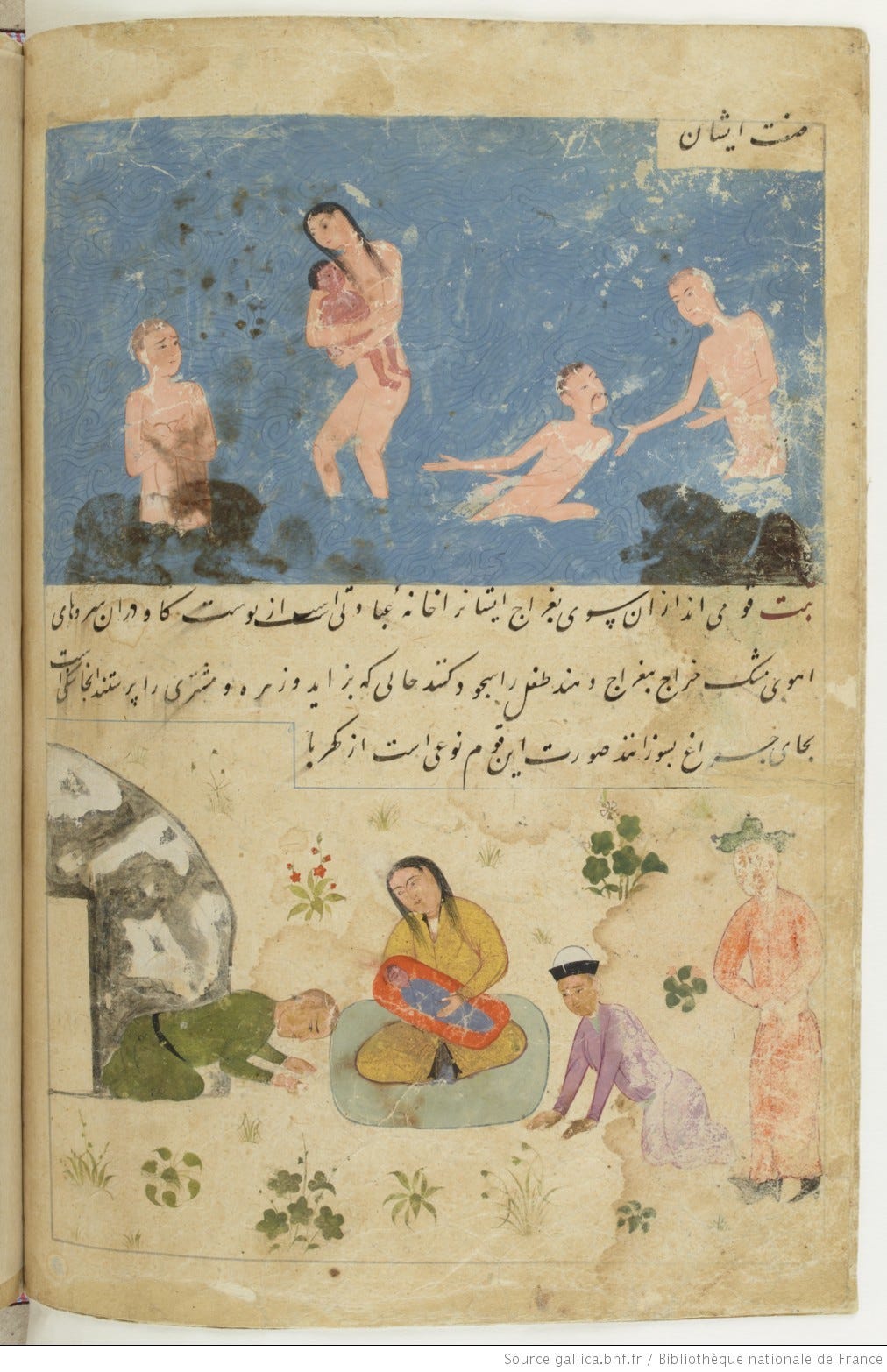

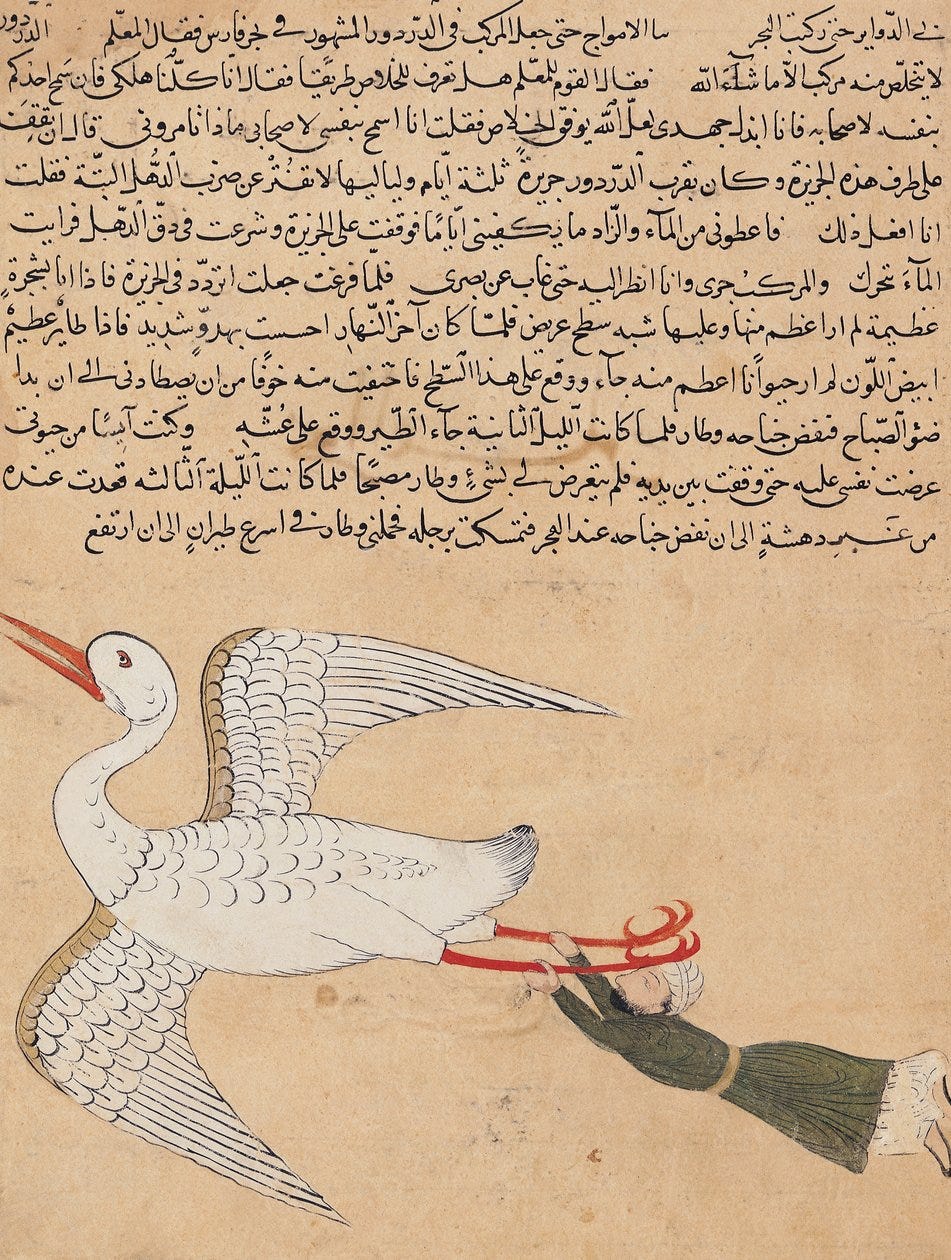

The 13th-century Arabic text The Wonders of Creatures and the Marvels of Creation (ʿAjāʾib al-makhlūqāt), which I once studied, names this very posture of attention. Its author, the Persian cosmographer Zakariyyā al-Qazwīnī, opens his account of human life with a line that reads like instruction as much as praise: “In nature are wonders.” A few pages later he goes closer still: “All powers are present in the drop”—the nuṭfa, the first seed in classical embryology—already carrying the dance to come: membranes, organs, temperament; and, as the tradition has it, the angel breathes spirit and life rushes forward. The lesson is plain enough: hold still, long enough, and the world enlarges itself.

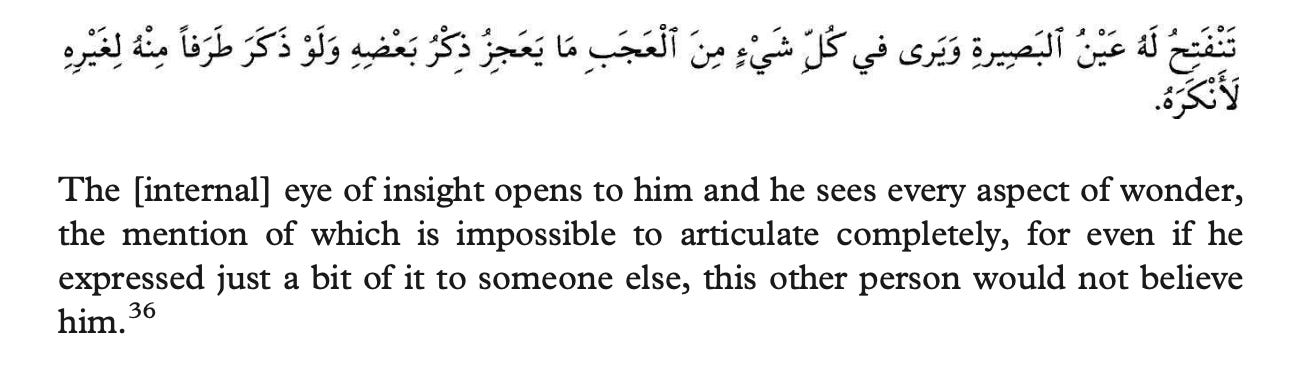

The philosophers of the medieval Greco-Islamic world treated bewilderment (ḥayra) as an ethic of attention. Not confusion, but a chosen pause—the stillness in which perception unsettles and enlarges the mind. They paired wonder (ʿajab) with instruction (ʿibra): first astonish the senses, then let the meaning follow. To see well was to allow oneself to be reshaped, to admit that vision carried its own mysteries and demands. Qazwīnī went further, confessing that when the inner eye opens, a person “sees every facet of wonder,” and that to describe even a fragment will sound implausible. Some truths arrive only in the presence. You kinda had to be there.

The tradition is also blunt about how gazing works. One Byzantine account in Morgan’s work describes John Chrysostom cradling an icon of St. Paul “as if it were alive,” speaking to it the way one might to a companion. Centuries later, an Armenian workshop of painters would boast that “our art is light itself, for young and old each understand it”—a reminder that images steady us before explanations ever arrive.

A newborn can make even a secular house feel briefly religious. Someone shows you where to wash your hands and where to stand. A partner eases the chair closer. A friend sets soup on the counter and speaks in low-lit vowels. Adults start speaking in tongues: coos, half-sung nursery rhymes, and words so small they don’t qualify as language anywhere else on earth. For a few weeks the household keeps the rites and everyone knows the steps. No creed is signed; the hour writes its instructions directly on the body.

Even the phone submits to the hour: darkened in a pocket, or lifted to glow like a candle in the nave. Our thumbs rehearse the gestures of another age. Where once a rosary measured prayers, bead to bead, breath to breath, we scroll for reassurance, tracing patterns in the feed, waiting for a sign.

You stand above the child, round and luminous as an orb, the way a believer steadies before an icon. The air changes. The minutes come loose.

Then the baby stirs, and the scene forgets its cleverness. We are permitted, for once, to be bewildered. The rise and fall of a chest becomes a metronome; the minutes slacken. A small hand opens and closes. It feels like a paradox you can hold in your hands: you are lifted out of time and dropped deeper into it at once.

By morning the lists return, as they should. The day resumes its errands, its bodies to be tended. We are, after all, leaky bags of salt and water, always in need of management. Yet somewhere between the sorcery of the night and the pediatrician’s portal, the old truth presses forward: we find ourselves again before the icon, the idol, the image. You take off your shoes at the threshold. You bring what you can carry. You look—and if you look long enough, the looking remakes you, drawing you beyond yourself while anchoring you, utterly, in both the here and there.

This is shockingly beautiful! Congratulations.

Glorious! 🧡💫🧡💫🧡