What Yglesias Gets Wrong About the 1850s

Republicans forged purpose out of disparate interests and factional conflict.

Yesterday, the nation’s blogger-of-record Matt Yglesias paused some of his usual online sniping to call me “one of the smartest people in left politics” in a long essay on some of my writing from the past year. Which just goes to show: people who think I’m smart can still get history wrong and misunderstand what I’m actually saying. It was also probably one of his least clicked pieces — nobody’s chasing traffic with a deep dive into 1850s Republican ideology — so I take his arguments as genuine rather than cynical.

Before we argue about the 1850s, it’s worth asking why we’re talking about them at all. In an interview, Eric Foner recalled that George W. Bush’s senior political operative Karl Rove “said he learned how to build a political coalition” from the book Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. Foner’s seminal work is a deep dive into how movements, factions, and parties can turn many interests into a political force that can win, govern, and transform a nation.

Yglesias makes three core claims. First, “There just is not a singular transcendent issue of our time,” so analogies to the 1850s falter because “the Abolitionists and Radicals were singularly focused on the slavery issue.” Second, today’s left “is not making a specific ask.” Third, it often seems “we’re not bargaining over issues at all, but over control.” I agree on the premise: slavery’s moral, economic, and political place has no modern analogue. I said the same in my piece. But the way he uses the history of the 19th century misses how the Republican Party’s purpose was forged and then debated inside a contentious coalition rather than pre‑agreed by everyone from the start.

1) The 1850s were not “one issue.” Republicans forged one politics.

In the 1850s, Republicans did not begin with consensus that slavery was “the issue.” Abolitionists and Radicals pressed for immediate emancipation, while moderates wanted to contain slavery in the territories, and conservatives hoped to tamp the conflict down so the government could return to tariffs, railroads, and banking.

For example, as Foner argues in Politics and Ideology in the age of the Civil War, Northern labor activists thought slavery was just one symptom of a larger economic system that also degraded northern workers; abolitionists insisted slavery was the root cause of all labor’s problems and had to be eradicated first. Each side even drew different lessons from the “Lords of the Loom and Lords of the Lash” alliance: labor saw northern capital and southern planters as partners in exploitation, while abolitionists cast slavery as the singular source of corruption. That tension helps explain why abolition remained a minority cause for decades—evangelical reform could break the silence around slavery, but it also alienated many northerners wary of moral absolutism.

The breakthrough came with free-soil politics in the late 1840s and early 1850s. By making the expansion of slavery into western lands the central issue, Republicans created a meeting ground where abolitionist moral fervor and labor’s demand for independence converged. They also dropped the Radical push for equal rights for free Black people but adopted labor’s broader definition of freedom (“free labor”) as economic independence.

Lincoln sharpened the point: the workingman’s right to the fruits of his labor could not coexist with a system that turned people into property. Republicans turned labor’s fears about wages and land into a critique of the Slave Power. The genius of the coalition was inventing that adversary: a Southern oligarchy that had captured Washington through minority rule. As Eric Foner writes, this became the “glue” that bound abolitionists, radicals, moderates, and conservatives who otherwise clashed over pace and scale.

The focus on “no extension” didn’t emerge naturally; it was hammered out through years of factional struggle, then turned into law—Homestead, the Pacific Railway, land-grant colleges, and, in wartime, emancipation and civil rights. Republicans fused moral urgency with material interest, channeling farmers, workers, industrialists, and abolitionists into one majoritarian project. They also cast it as mass and class politics, as historian Matt Karp argues: the many against “a tiny aristocracy of slave lords.” That coalition logic, more than a single-issue crusade, made antislavery into a winning politics.

By 1860, Republicans had to decide what they stood for beyond stopping the spread of slavery. As Foner notes, the Chicago party convention adopted planks for “a tariff, internal improvements, a Pacific railroad and a homestead law.” Former Whigs demanded a national economic program, while even ex-Democrats conceded the party “would have to broaden its platforms.” As Chicago’s mayor John Wentworth admitted, “I do not see what we are to do without some financial policy.”

The hardest fight was over tariffs. To carry Pennsylvania without splitting the coalition, Republicans settled on “some incidental protection to the iron interest, avoiding, nevertheless, the idea of a high tariff.” The word “protection” never appeared in the platform at all.

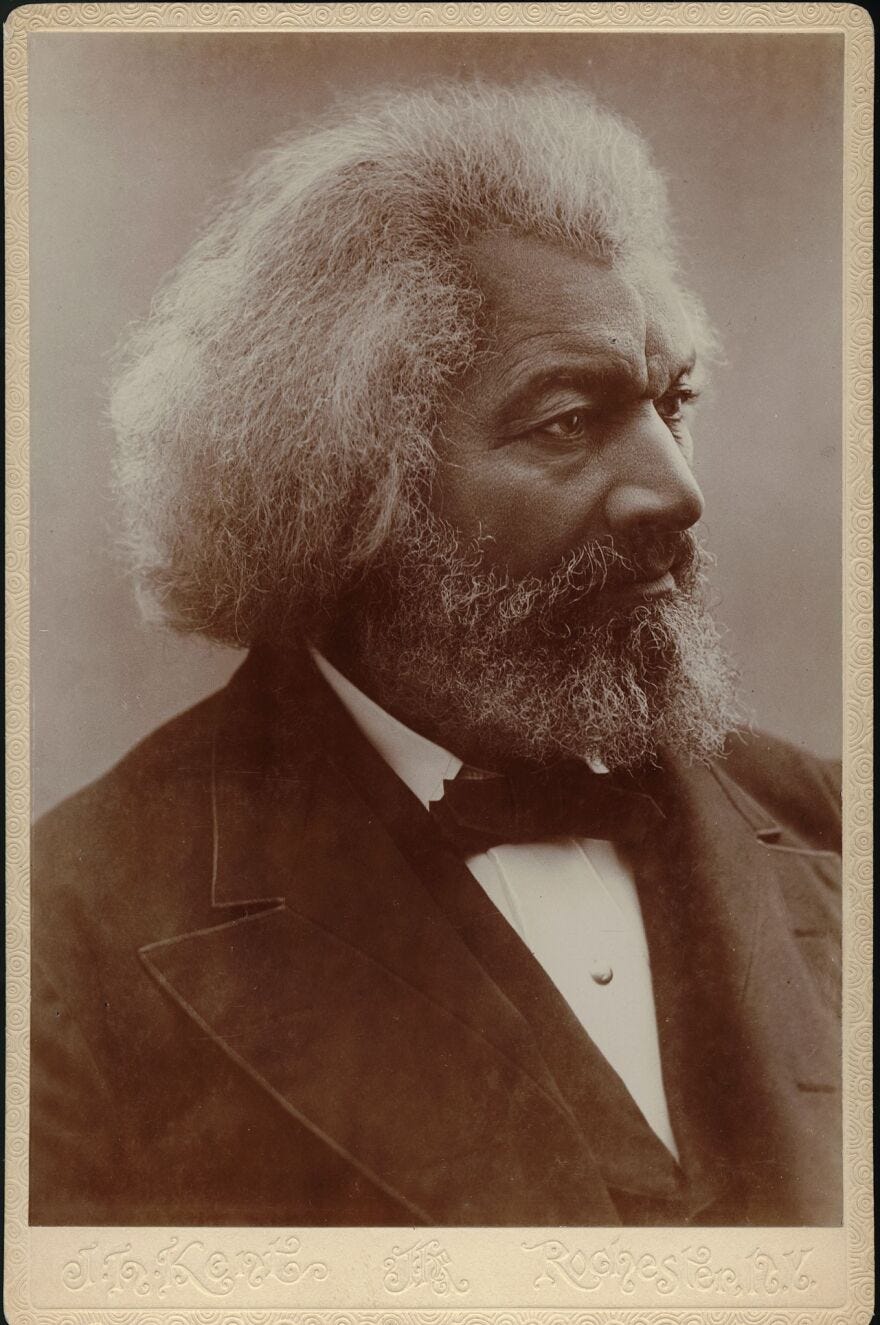

Strategically, the party stressed anti-slavery in the radical North and West, while foregrounding tariffs in more conservative districts. The result was a deliberately blended agenda: antislavery at the core and an economic program broad enough to win. The coalition also gestured toward pro-immigration policies that would echo later in Frederick Douglass’s 1869 “Composite Nation” speech, which urged Americans to embrace Chinese immigration and a genuinely multiracial democracy:

I want a home here not only for the Negro, the mulatto and the Latin races, but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours. Right wrongs no man. If respect is had to majorities, the fact that only one-fifth of the population of the globe is white and the other four-fifths are colored, ought to have some weight and influence in disposing of this and similar questions.

We are a country of all extremes, ends and opposites; the most conspicuous example of composite nationality in the world. Our people defy all the ethnological and logical classifications. In races we range all the way from black to white, with intermediate shades which, as in the apocalyptic vision, no man can name or number.

2) Junior partners tend to demand, senior partners decide and forge.

Yglesias argues the left today “is not making a specific ask,” unlike the Radicals and the Republicans of the 1850s. But that blurs the lines. With much fewer seats than moderates, Radicals functioned as the junior partner: ideological, horizon-setting, relentless about forcing the party to confront slavery and transform American society. The Republican Party’s moderate leadership was the senior partner: focused on electoral majorities, winning elections, and passing laws.

Radicals made clear they wanted far more than stopping slavery’s spread—Foner notes they demanded “abolition in the nation’s capital, an end to the use of slaves in federal employment, and eventually…emancipation in the South itself.” Once war began, those aims widened into Reconstruction: “restricting the power of the planters, protecting the rights of the freedmen, and transforming the South into a democratic (and Republican) society.”

The party, meanwhile, had to distill this into something a majority could vote for. That’s why the focus was “no extension,” and why Lincoln—who knew “no politician is going to kick his base out”—translated radical pressure into moderate language and policies.

Foner puts the Radical role split plainly in an interview with Jacobin Magazine: “The abolitionists show you that a very small group…can accomplish a lot by changing the discourse…the role of radicals is to stand outside…and put forward the moral imperative.” If they persuade people, “then politicians will come up with a plan to do it.” Politics, he adds, is “people acting together, even if they don’t love each other, for a common purpose.” Lincoln, a moderate, still knew abolitionists were part of his base—“no politician is going to kick his base out.”

As Lincoln himself famously described his party’s radicals, “They are utterly lawless--the unhandiest devils in the world to deal with--but after all their faces are set Zion-wards.”

The lesson isn’t that today’s left has too many causes. It’s that Democrats haven’t done the senior-partner job of choosing a unifying program and turning movement energy into governing power.

After Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez defeated Joe Crowley and began using her platform to push inequality and the Green New Deal, I went to see historian Barbara Fields at her office hours and asked whether the 1850s and 1860s offered any lessons, albeit not straightforward, for today—with AOC in the lane of the Radicals and Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi in the lane of moderates like Lincoln. Fields agreed that there were some parallels, but her response was blunt: “Schumer and Pelosi don’t have a Lincolnian bone in their body. They don’t feel the forces of history moving beneath their feet.”

Her point wasn’t mystical. Lincoln’s strength was taking radical pressure and turning it into a program a majority could vote for. By contrast, she suggested, today’s Democratic leaders treat politics as a permanent red–blue campaign of fundraising rather than defining, defending, and advancing a majoritarian program that reshapes America’s political economy and the lives of the American people.

3) What Yglesias Calls ‘Control’ Is How Coalitions Work.

Yglesias says the left and center today are “not bargaining over issues at all, but over control.” But that’s exactly how junior partners behave in American parties without formal coalition agreements. Factions fight for leverage so the senior partner can’t pocket their votes and paper over divisions with a lowest-common-denominator program—one that tries to please everyone, satisfies no one, and leaves the deeper contradictions in the political economy untouched.

The mid-19th century Republican Party had this internal fight all the time. Conservatives wanted a quick win to “end the slavery controversy and allow the federal government to turn its attention to…national economic development.” Radicals saw that same victory as “only the first step in a relentless crusade” to transform Southern society. That was a fight about agenda-setting power—control, in Yglesias’s word—inside a coalition that still had to stay majoritarian. As political scientist Daniel Disalvo writes in Engines of Change: factions are “agenda-setting vehicles and engines of political change.” They generate new ideas, push them onto the agenda, and contest over what the party actually does. When party leaders can’t synthesize factional conflict among the senior and junior partners, the pressure looks scattered and gets mislabeled as nihilism.

Because of how U.S. parties work in a winner-take all, two-party system, the party leadership optimizes for swing seats, donors, and governing bandwidth, which means sanding off sharp edges and deprioritizing issues that complicate a majoritarian message; the American left then often is left on precisely those neglected, deprioritized, or slow-walked items--clean energy economy, Medicare for All, Palestine, rent control, antitrust--not as hobbies, but as leverage to force agenda inclusion and build constituencies the party would otherwise under-resource. In practice, much of that agenda looks less like scattered and utopian wish-casting and more like the platforms of social democratic and democratic socialist parties across much of Latin America and Europe.

TLDR;

There is no modern equivalent to slavery’s central role in 1850s politics. Lincoln’s GOP is not Jeffries’s Democratic Party, today’s left is far weaker than the Radical bloc (I would like for it to get sharper), and slavery’s unique evil has no peer. But the history is still instructive. Republicans didn’t win because the movement had one demand; they won because Radicals expanded their influence, forced moderates to confront the Slave Power as the defining political problem, and pushed the party to translate many demands into a majoritarian program—the Free Soil, Free Labor agenda—and then govern on it.

That’s the part of the analogy that carries forward. In a big-tent party, junior partners—the ideological factions—press contradictions, draft concrete policies, and fight until the leadership has to pick sides on issues they’d rather avoid. Senior partners focus on holding majorities, smoothing risk, and keeping the message broad. The senior partner optimizes for swing seats and risk control—count votes, calm donors, keep the message and vision broad (“better health care”) rather than binding (“single-payer with X”). Understanding this helps explain why the party doesn’t really have a clear message or platform until the presidential nominating contest, after the party’s factions battle it out for influence.

When party leadership and its junior partner can’t synchronize their roles, the push for clarity gets mislabeled as a power grab, the agenda drifts, and blame flows. But when the bargain works, movement-aligned factions provide substance and energy, and the party turns that into votes, legislation, and durable governing power.

Until AOC and her ilk, there was no radical group that could be a productive junior partner. The purity pony left could not partner with anybody, and the mainstream Democrats were right to mollify and ignore them. (Jesse Jackson was no purity pony, but he could not subordinate his career to his cause: a very dangerous ally.) But we have developed a much better kind of radical over the last two decades or so: eyes on the horizon, and feet on the ground. Schumer & Co. may not have recognized this.

That's a problem with old people. Their view of the world is as accurate as anybody's--maybe more so, since they have seen more things. But their accurate view is often that of a past world. (I'm an old person, and have suffered from this problem.)

Why can’t the fight against autocracy and the fight to save our freedom and democracy be important enough to unite us.