You Can Hold Her Now

What happens when our friends meet our baby (and themselves) for the first time.

The first couple who came to meet our daughter arrived early, wearing that slightly soggy expression of people who brought an umbrella but still lost a negotiation with the rain. She walked in first, balancing flowers and a Tupperware of something that steamed politely through its lid. He followed with a stuffed animal with eyes so large and pleading it looked like a minor Pixar character fated to die so the real plot could begin.

We did the polite choreography. Coats heaped on the chair, compliments exchanged like business cards. “You look amazing,” she said to my partner, which was kind, if not strictly true—my partner still a kind of construction site in progress, held together with mesh and resolve. Our daughter lay in the middle of the couch in footed pajamas, blinking at the overhead light with the grave, unblinking gaze of the very new.

“Do you want to hold her?” the wife asked her partner, about three minutes in.

He smiled at the baby, smiled at us, then looked down at his hands as if they’d just landed in his lap from a great height. “Yeah,” he said. “In a minute.”

“Come on,” she said. “You have to start sometime.” Her tone was breezy, but the sentence had weight to it, like a throw pillow with a brick sewn inside.

He laughed. “I just don’t want to, like, drop her,” he said, drawing the last word out as if it were a punch line. The joke sat there, small and earnest. We all did the little polite laugh you do when someone has arranged one on the coffee table.

Our daughter, sensing that something ceremonious was afoot, made a sound halfway between a hiccup and an old modem connecting to dial-up. Everyone leaned in. No one moved. I felt my own arms twitch, ready to intercept, the way they do when someone reaches for a very full glass too close to the edge of the table.

Eventually, inevitably, he reached out. Watching him, I remembered my own first days, how I had held her like contraband, convinced some invisible authority would materialize and issue a citation for Illegal Neck Angle. His body did the same math mine had done: the uncertain descent of hands, the small panic twitch when she shifted her weight. And then his shoulders went rigid and climbed toward his ears—this automatic, doomed attempt to stabilize the situation by squeezing every muscle he had, as though he were holding either a live explosive or a baby-sized bag of trash someone dared him to carry. His face ran through its usual slideshow: charmed, anxious, bored, flattered, mildly resentful. Then she flopped an arm against his wrist and he made a face halfway between a wince and a grin.

“That’s good,” she told him. “See? You’re doing it.”

If this only happened once, I might have forgotten it. But they kept coming. Different straight couples, same scene. One pair brought a Tupperware of soup the size of a helmet. Another brought a bag of expensive coffee and a plant we later murdered. Always, there was a version of the moment.

“Do you want to hold her?”

“Yeah, I will. In a bit.”

“You can now.”

“I’ll wait till she’s…less upset.”

“Just take her.”

And then a little domestic tribunal right there on the couch, in front of our houseplants and their own future. She prosecuting, he hedging, me and my partner playing a sort of jury, though we hadn’t asked to be nominated.

What I started to see, after a few repetitions, was how rehearsed their lines were and how naked the stakes. The women seemed to experience our living room as a safe rehearsal space for a larger performance. If he could not hold our baby, how would he hold theirs? The men seemed to experience it as an exam they hadn’t studied for, one that had somehow been scheduled earlier than they’d expected.

What I saw on their faces wasn’t just fear, it was something older and stranger—hayra, that bewildered-wonder you find in other languages, where being stunned and being lost are the same condition. For a second they looked as if they’d stepped off the well-lit path of their lives and into a little thicket: not running away, just suddenly unsure of how the ground worked.

In Arabic, Persian, and Urdu hayra sits right next to the words for amazement, for marvel—confusion as a kind of awe—and that was the expression as they took my daughter into their arms. They were frightened of dropping her and, underneath that, quietly amazed that this warm, breathing person existed at all and was, absurdly, trusting them.

Their wives didn’t seem to be lost in a forest. They were in a different ecosystem entirely: the practical, spreadsheeted tundra of ovulation apps and prenatal vitamins, of “if we got pregnant in March that would mean a December baby, which would be hard for school cutoffs but good for tax purposes.” They were already emotionally jet-lagged, living months ahead.

If you’ve ever done a long-haul flight with someone you love, you know what it’s like to be in different circadian rhythms in the same row. One of you is ravenous, the other is nauseous; one is desperate to sleep, the other is scrolling through movies. You’re in the same metal tube, hurtling toward the same destination, but your bodies are keeping different clocks.

Pregnancy makes that permanent. From even before the moment my partner saw two lines on a stick, her body recalibrated. Food tasted different; time moved differently; rooms picked up new danger zones. Her future had already been uploaded into her blood chemistry. My body, meanwhile, remained itself. I could still eat and drink what I wanted and not be overtaken by fatigue in the middle of the day. I could still pretend, for hours at a time, that nothing irreversible was happening.

So when these men say, “I’ll hold her later,” I hear not only fear but also lag. They are still on West Coast time, standing in a nursery that is already on East Coast time, already morning, already a future with two kids.

Of course, there’s more going on. There’s the quiet gender contract—the sense that she will be judged for not wanting kids, and he will be teased for wanting them too much. There’s the social script that still assumes women are natural caregivers and men are natural disasters unless heroically reprogrammed. There’s the memory of their own fathers—awkward hugs, or absent arms, or overconfident roughhousing—and whatever vow they have half-consciously made to be different.

Still, what I see most is the micro-expression that flits across their faces when their wife says, sharply, “Just hold her.” It’s the fear of being seen, by someone whose gaze matters more than any other, in a moment of total incompetence. They are used to being evaluated on wit, on earning power, on taste in music. Suddenly the test is: can you keep a little stranger’s head from flopping backward. There is no curve.

When they pass the baby back—fingers reluctantly uncurling, shoulders snapping back to their usual width—there’s often a strange politeness in their thanks. “Thanks,” they say to us, as if we’ve let them drive our car around the block. Sometimes they tell us, quietly, that it was “easier than I thought.” Sometimes they don’t say anything, but later, over the last cup of tea, they might confess to my partner, “I can’t believe you made that. I can’t even hold her right.”

She says, “You will.” She says it like a promise, like a curse, like a hope.

After they leave, the apartment is suddenly too quiet. Our daughter, overloaded by stimulation, crashes hard, her arms thrown up in that ridiculous startle reflex pose that looks like surrender and is actually some ancient neurological holdover from when our ancestors fell out of trees. The couch remembers all the performances it has hosted: brave, awkward, bored, hopeful. We sit there in the wreckage.

“Do you think they’ll have kids?” I ask.

My partner shrugs. “I don’t know.”

Drafted is a good word for what happens next. There is a knock on the door—your baby’s first cry—and your life is suddenly conscription. You can say “I’m good” all you want; the war has already started. The only choice you really have is whether you pretend you’re just visiting the front lines or admit you live there now.

I sit there, feeling overwhelmed and tender toward everyone who sat on that couch that afternoon. When I think about my own first days with the baby, I remember holding her and waiting for someone to tell me I was doing it wrong. I remember my partner putting her hand over my hand and shifting the angle of her head without saying, “you’re bad at this.” Fear and love were so tangled I couldn’t tell them apart. I suspect that’s true for the men on the couch, too.

It would be satisfying, narratively, if I could report that on the fifth or seventh visit some man walked in, reached straight for our daughter with easy confidence, and broke the spell. It hasn’t happened yet.

For now, the ritual continues. Someone knocks, hands over a Tupperware and a toy, sits on our couch, and is quietly invited to decide what kind of person they are. Our daughter, who has no idea she’s become a kind of litmus test, chews on her fist and watches the light bend through the window, making shifting shadows on the walls. She studies it as if that’s how air is made—out of the small, nervous efforts of adults trying not to drop anything.

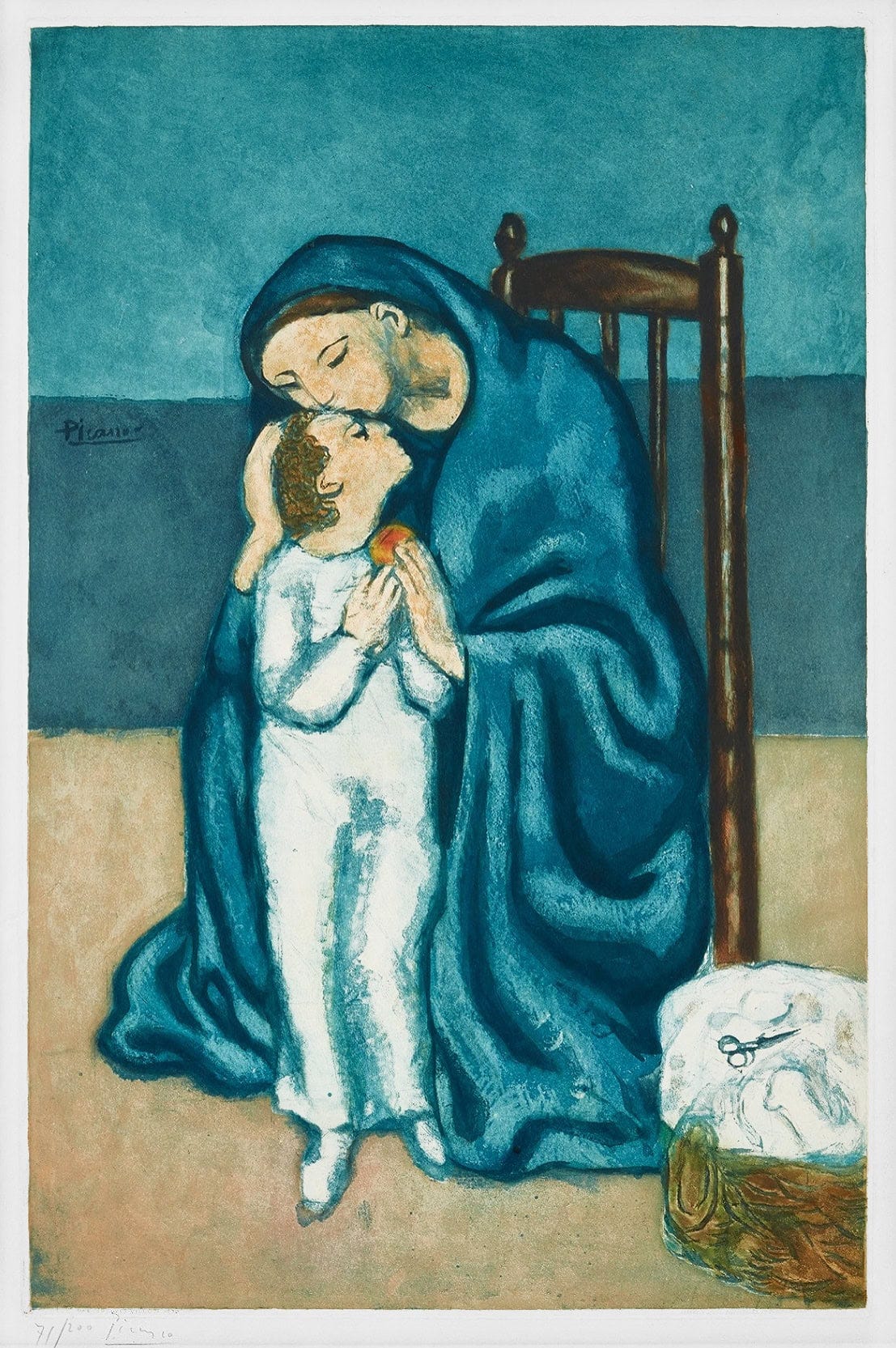

How tender and weird. A prayer: one day we will become a people used to seeing our babies cradled in the arms of their fathers. Interesting, and maybe prophetic as well as explanatory, that grandfathers mostly look like old hands in this role. Congratulations on the love and bravery it takes to assume the mantle of parents in this world.

Beautiful. thankyou Waleed.

My son was born by C section. His mother was taken off to the recovery area. The nurse picked him up and was about to walk away. I said 'could I hold him'. It was a life changing moment.