Zohran, NYC's Old New Majority, and 2026

Plus four lessons on Democratic populism.

At a moment when much of the Democratic Party still stumbles to say what this country is for, Mamdani’s answer sounds deceptively simple.

The first time Zohran reached out to me on his potential run for mayor, he wanted to talk about the New Yorkers who’d stopped believing politics was for them. He talked about the people checking out of Democratic Party politics—young people, Arab and Muslim communities, taxi drivers, the thousands of DSA volunteers who knock every door and rarely get treated as a serious bloc within the party, every single person worried about their rent and groceries who didn’t feel like the system was designed to help them in any way.

Zohran’s worry was simple: in a ranked-choice field with figures like Andrew Cuomo and Eric Adams, there wouldn’t be a progressive coalition big enough to win unless a candidate held two firm lines—be firm on Palestinian human rights and relentlessly focused on affordability. The point wasn’t TikTok or even his own win; it was to expand who shows up to vote, and why.

In the New York of the 1910s and ’20s, ethnic politics was both ladder and ceiling, and Fiorello La Guardia learned to climb with his head brushing the rafters. Republican boss Samuel Koenig warned Fiorello La Guardia in 1921, “The town isn’t ready for an Italian mayor,” urging him to stand down from a mayoral bid; La Guardia answered, “Sam, I’ll run. So long as I have five dollars in my pocket I’ll be all right” Party bosses and patrician elites read the city through nativist arithmetic—“the town isn’t ready for an Italian mayor”—even as the electorate was tilting toward immigrants, women, renters, and reformers.

La Guardia tried to fuse those worlds: a war-hero son of immigrants who spoke to Italians and Jews in their own neighborhoods, and to “good-government” progressives about clean streets, honest budgets, and the five-cent fare. The machine treated him as an apostate when he defied direct-primary repeal and corporate transit interests; Republican leaders fretted over his independence; Tammany scorned his cross-ethnic appeal.

The same skepticism that kept La Guardia from the 1921 nomination fed a broader realignment: mobilizing women newly enfranchised, socialists and communists, renters overburdened by taxes and fares, and voters tired of bosses who treated City Hall as private property. His “not ready for an Italian” moment, in other words, marked the moment when a city built by immigrants began to demand representation equal to its labor, and a politics that served public goods over party discipline.

La Guardia, the half-Italian, half-Jewish son of immigrants who rose from a tenement to City Hall, saw in New York a living answer to the nativists’ sneer. In Congress, as the nation turned against newcomers, he railed against the hysteria that would later define the 1924 immigration quotas. It was “mob rule,” he said, “a blot on the history of the American Congress,” a betrayal of what he called the true American creed. He accused his colleagues of following “the rules of the Klan and not … the American Congress,” and warned that the architects of racial quotas were driven by “narrowmindedness and bigotry,” by a “fixed obsession on Anglo-Saxon superiority.” The spirit of the Ku Klux Klan, he said, “must not be permitted to become the policy of the American government.”

Decades later, as mayor of the most polyglot city on earth, he would turn those convictions into a civic gospel. “For here people live,” he told New Yorkers on the radio, “all their ancestors having come from every country and clime in the world, living in peace.” His multiracial democracy was not a dream deferred but a daily, crowded fact—Italians, Jews, Irish, and Poles composing a new coalition of white ethnics who, in his mind, could redeem the promise of America not by blood, but by solidarity.

In John Ford’s The Last Hurrah, Frank Skeffington—an aging Irish-Catholic mayor—faces the city’s Protestant establishment: bankers, a bishop, men who still see themselves as custodians of civic virtue. They dress their veto of a slum-clearance project in the neutral language of “credit risk.” Skeffington answers with the life behind the ledger: kids playing in the street for lack of a park; pneumonia dragged out of cold-water flats. Then he names what the room won’t—the city isn’t just theirs anymore—and vows to open the housing on St. Patrick’s Day, marching it past their windows so it can’t be papered over.

The scene isn’t very subtle, but it clarifies a long American rhythm: power shifting from a patrician order that governs by gatekeeping to immigrant-rooted coalitions that govern by numbers and need. Power upstairs calls for patience; power downstairs asks to be seen. The live questions—who counts, who decides, does the boardroom still rule the street—frame the context for Zohran Mamdani’s wager about coalition politics in New York now.

After Democrats lost to Trump last year, Mamdani took meaning-making to the sidewalk. One camera, a hand-painted “Let’s Talk Election” sign, a few hours on Hillside Avenue and Fordham Road. He asked why working-class voters, almost all people of color, had voted for Trump—or stopped voting at all. The answers were spare and exact: rent that eats half a paycheck, groceries that climb by the week, buses that don’t come, tickets that pile up. Gaza surfaced not as geopolitics but as proof of priorities: money for war moves instantly; money for living gets lost in process. The “culture war” so many pundits diagnosed looked, in the frame, like something simpler: a conversation about money, and what it means to be seen.

I sent the clip to every reporter and consultant I could think of still explaining the Harris defeat as mostly a backlash to “wokeness”—that the party had gotten too moral, too online, too interested in scolding. The replies that came back were half-embarrassed, half-awed. The culture war they’d been debating turned out to be something simpler: a conversation about bills, and what it means to be seen.

Outside the at-capacity hall on election night, the cold had a way of sorting who really wanted to be there. Dozens of twenty-somethings in borrowed coats—and, just as loud, South Asian and Arab aunties and uncles with thermoses and flags—stood in a loose crescent around a speaker on a window ledge, passing hand-warmers and gossip. The mood was buoyant, and beneath it ran a plainer claim about how the city and the country works.

Zohran Mamdani’s electoral success offers Democrats four lessons as they head into 2026. belonging, looting, rigging, cost. Each theme answers a different public intuition—who’s ignored, who’s stealing, how they get away with it, and what it costs the rest of us. Together they describe a politics of moral belonging and material relief—the kind Democrats once knew how to win with. The expression of these themes will differ by geography—not everywhere will sound like Queens—but wherever economic populism takes root, these are some of its core features.

The Belonging. Before corruption and costs, there’s a prior question: are you inside the “we”? Mamdani makes that explicit. Immigrants aren’t a problem to manage; they’re the story—the labor, language, and lived reality that make New York work. The Hillside/Fordham tape shows this. A city that takes your taxes and time but treats you as background won’t feel like home until someone names you in the first person.

Mamdani’s approach is deliberately simple and very old New York: widen the circle, then argue policy. He says it as a creed and a contract: “We will fight for you, because we are you.” In his victory remarks, he thanks the people politics forgets—Yemeni bodega owners, Mexican abuelas, Senegalese taxi drivers, Uzbek nurses, Trinidadian line cooks, Ethiopian aunties—and tells neighborhoods from Kensington to Hunts Point, When people hear themselves in the “we,” they connect dignity to dollars—and the coalition that wasn’t invited becomes the one that ultimately might decide.

Where others reach for technocracy or moral panic, Mamdani starts from belonging. He reminds voters that the city’s collision of languages, histories, and hungers isn’t an accident of globalization but a democratic experiment—whether we came here merely to survive one another, or to build something that proves our common humanity was real all along.

The Looting. Zohran told a story about corruption that named names and showed the pattern. Adams, Cuomo, Trump—different specifics, same vibe. A check buys access; access steers a contract; the public finds out after the deal is done. Voters recognized the rhythm because they’ve seen versions of it for years. And when the camera shifts to Washington, the picture sharpens: a Mar-a-Lago “Gatsby” party the week SNAP and health care face cuts; a pardon that benefits a crypto billionaire linked to the first family’s business ventures; foreign money moving into that venture as export rules tilt. Taken together, it reads as one scheme: public power used to enrich a few.

The Rigging. The quiet heist of democracy has two faces: performance and procedure. The spectacle—the National Guard on standby, ICE raids staged for TV, talk of troops in cities, threats to networks from Air Force One, pressure on platforms to “turn the dial”—is meant to broadcast strength and frighten dissent. Behind it runs the quieter work: rewriting maps, purging rolls, criminalizing election workers, seizing local boards, inventing “fraud” squads, changing rules to reject more mail ballots, flooding voters with disinformation. One part terrifies, the other tilts. Both aim at the same end—control the system, punish enemies, reward friends, and keep power flowing upward.

The Cost is where the larger argument comes into focus. We don’t need to separate “corruption” from “groceries.” They feel both as the cost of a system that answers fast to donors and slow to everyone else. You can see it everywhere: a lobbyist’s client gets a meeting while a pharmacy denies a claim; insulin sells like jewelry; child-care bills climb as tax breaks tilt upward. When Trump says he “won on groceries,” he’s naming the terrain. Democrats should meet him there—showing, in plain numbers, how rules written for insiders land in the family budget, and how rewriting those rules could make a month’s expenses finally add up.

That thread held Mamdani’s policy narrative together. It started with his work on taxi-driver debt relief—a real win, with names and families attached—and moved to a list people could feel on a weekday: freeze rent, make buses faster and free, guarantee universal child care. The aim was simple but radical: restore a measure of order to lives lived on the edge.

They’re looting the place; they’re rigging the rules to keep looting; and while they do, working families are getting crushed month by month. Our job is simple: end the corruption, take power back from Trump and his corrupt billionaire friends, and make life affordable again for the people who make this country run.

What stayed with me after my meeting with Zohran was that he didn’t sound like a man auditioning for the part; he sounded like someone trying to gather a people who’d drifted from politics altogether—young voters, Arab and Muslim neighbors, taxi families, the tireless door-knockers—and teach them how to move together again. It felt less like ambition than stewardship: organize a bloc, return it to itself, and be ready—if that’s what the moment demands—to hand its power to another so the work can outlast you.

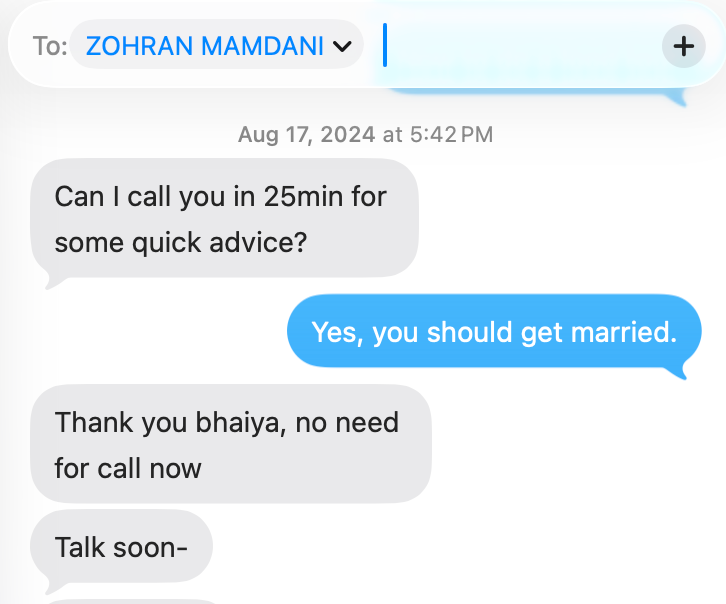

PS: If you’ve made it this far, here’s your bonus. Things are working out for ZOHRAN MAMDANI, who, like every self-respecting immigrant uncle, insists his name goes in your phone in ALL CAPS.

Alas, you’ve fallen into the same trap as many others: LaGuardia was 100% Italian. Both of his parents were born in what would

become part of Italy. His father

was a lapsed Catholic; his mom from a distinguished Sephardi family. He was fluent in Italian

& Yiddish. Also important: his

socialist acolyte/ally, Congressman Vito Marcantonio

of East Harlem.

Waleed,

What an outstanding article and comparison. I was thinking about the comparison with LaGuardia last night. Mandani is a brilliant man and shrewd politician. He will be had to demonize, though Trump, MAGA, and the Right Wing media will try. They are shitting all over themselves, the panic is visible.

I’m not a New Yorker, but I have always admired the spirit of the city and its people.

All the best and as always, watch your six.

Steve Dundas