One City at a Time: Trump Sends National Guard Into D.C.

Lessons from the 1850s abolitionist fight against federal overreach.

On August 11, 2025, President Donald Trump announced that he was seizing control of the Metropolitan Police Department of Washington, D.C., and deploying 800 National Guard troops to the city’s streets. The justification was a “public safety emergency” in a city with crime rates near a 30-year low. Trump did not simply present this as a matter of governance; he staged it. Flanked by his Attorney General and Secretary of Defense, he described “bloodthirsty criminals” and “roving mobs” in the capital and vowed to “take our capital back.” He suggested that Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and other Democratic-run cities could be next.

This was not just about D.C. It was about distracting from his own corruption and scandals to build a narrative, one city at a time: Democratic governance is synonymous with urban chaos, and only federal authority, embodied in Trump, can restore order. It is a strategy as much about political theatre as about policy. It also has a precedent, though from a very different moral and political universe.

In the early 1850s, the federal government confronted a problem. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a cornerstone of the Compromise of 1850, required Northern states to assist in capturing escaped enslaved people and returning them to bondage. It criminalized those who resisted, compelled ordinary citizens to act as slave catchers, and stripped the accused of the right to testify in their own defense. For the South, this was a non-negotiable assertion of property rights. For many Northerners, it was a profound moral trespass. The act’s enforcement became a running series of confrontations between federal marshals and abolitionist civil society.

The enforcement strategy was deliberate. Federal authorities did not storm every Northern city at once. They moved case by case, city by city: Boston, Syracuse, Chicago. Each arrest was framed as an isolated enforcement of “law and order” against local lawlessness, in that case “abolitionist mobs” aiding fugitives. The aim was to make each episode seem sui generis, defusing the risk of a coordinated backlash, while sending a message to other cities that resistance was futile.

Slavery was a singular moral evil. The fight over the Fugitive Slave Act took place in a world whose injustices cannot be compared to today’s. What is worth remembering are the structures of power and the strategies of enforcement and resistance. In the 1850s, federal officials used “law and order” to justify targeted interventions in defiant cities, seeking to isolate each episode and break opposition before it could organize. Abolitionists and their allies learned to recognize these interventions as part of a larger campaign and to mobilize public opinion against them through politics, organizing, and media.

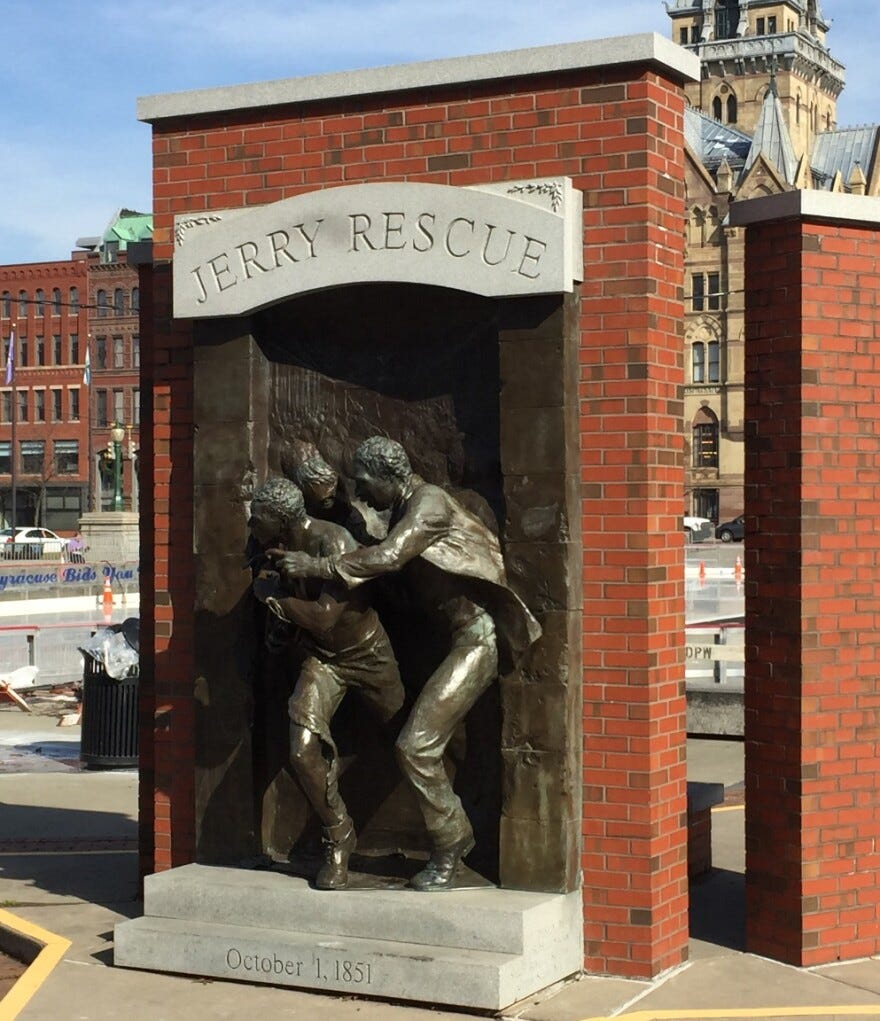

Abolitionists learned to break that frame. They treated each arrest not as a local loss but as a national test. When federal marshals arrested William “Jerry” Henry in Syracuse in 1851, the city happened to be hosting an anti-slavery convention. The news spread quickly. Church bells rang. An estimated 2,500 people, Black and white, surrounded the courthouse. A smaller group, armed with axes and a battering ram, broke in, freed Henry, and sent him along the Underground Railroad to Canada.

In Boston, when marshals seized Shadrach Minkins that same year, abolitionists stormed the courtroom in broad daylight, rescued him, and spirited him to Montreal. These were not random acts of defiance; they were the product of vigilance committees, communication networks, and a readiness to mobilize at a moment’s notice.

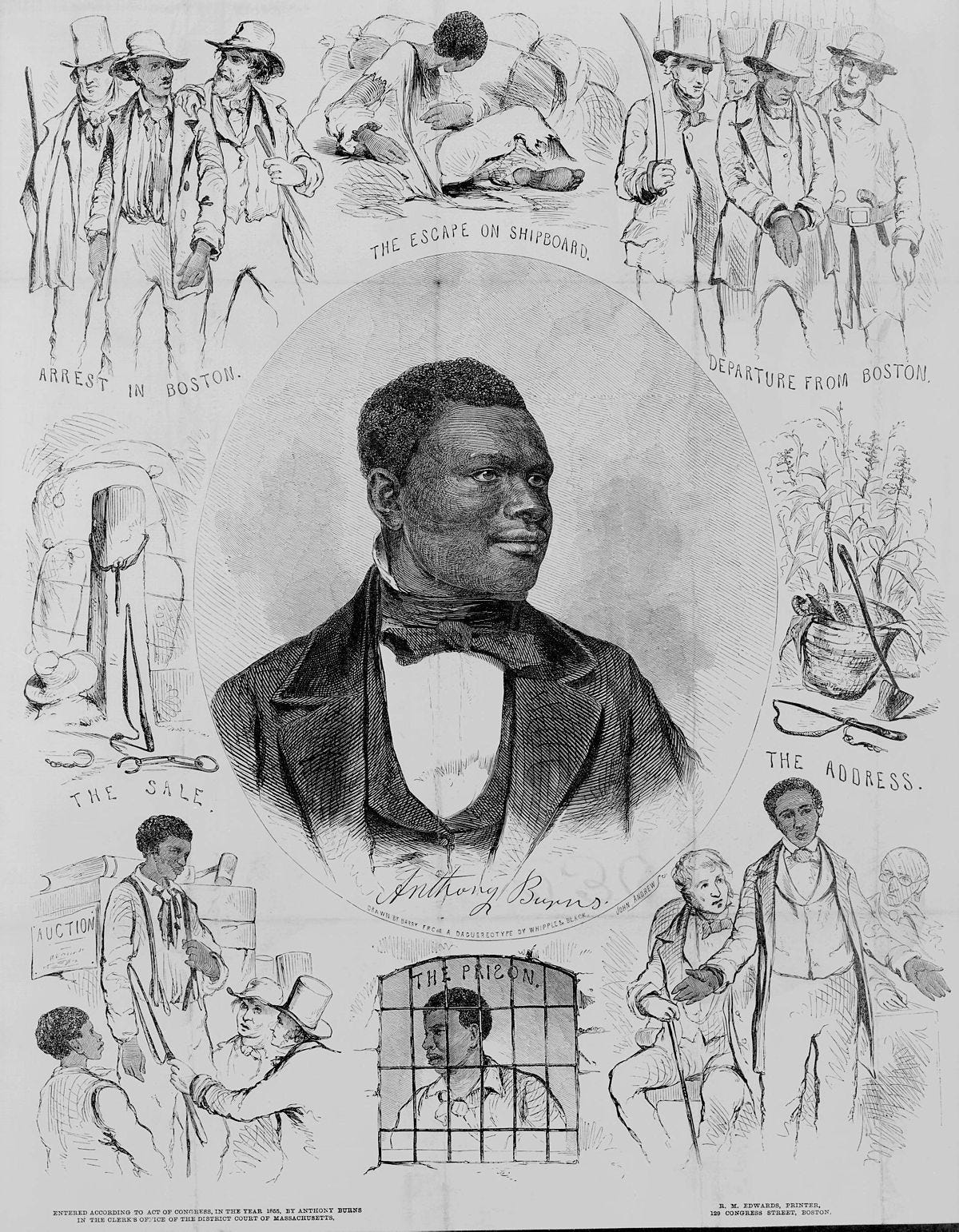

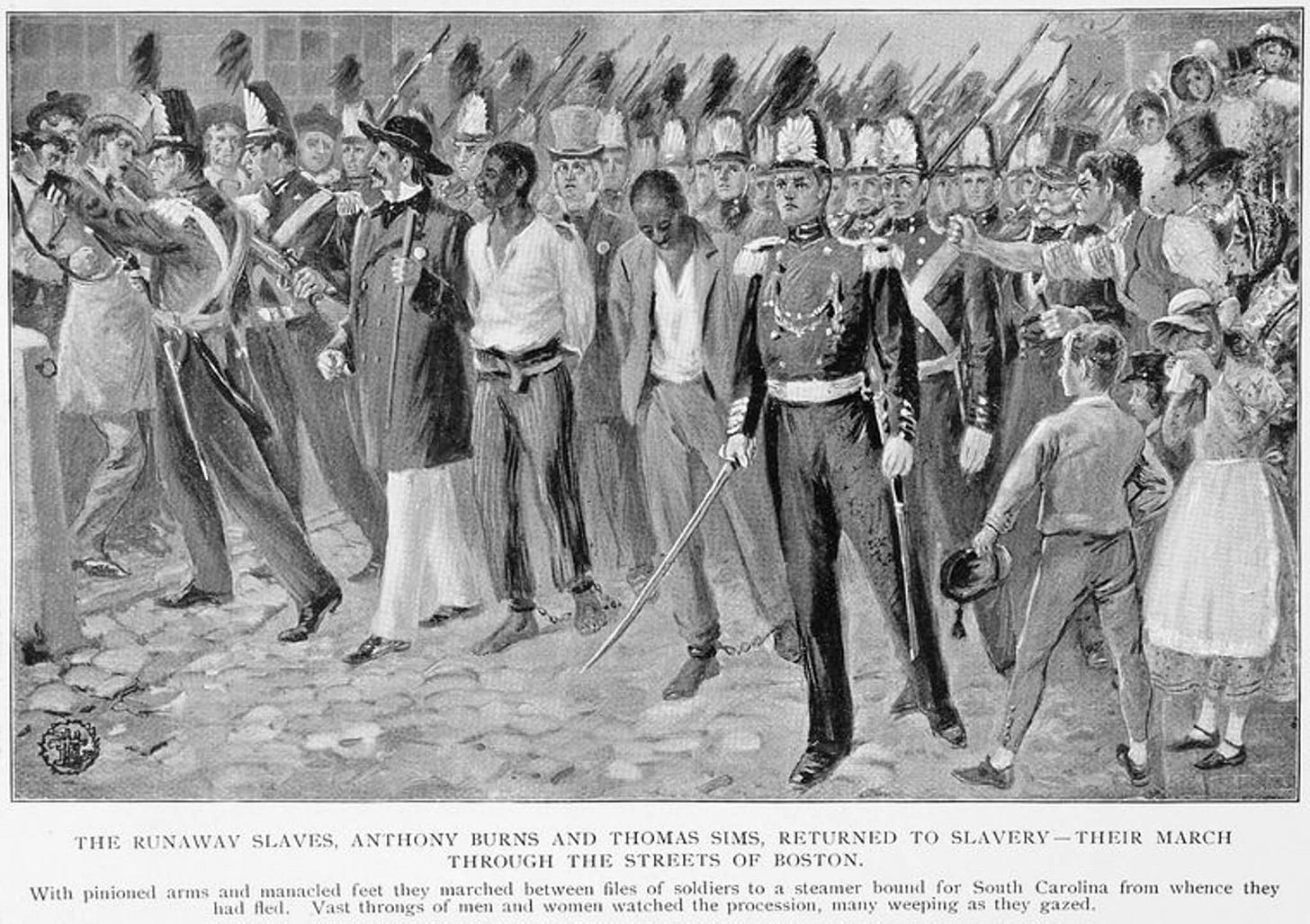

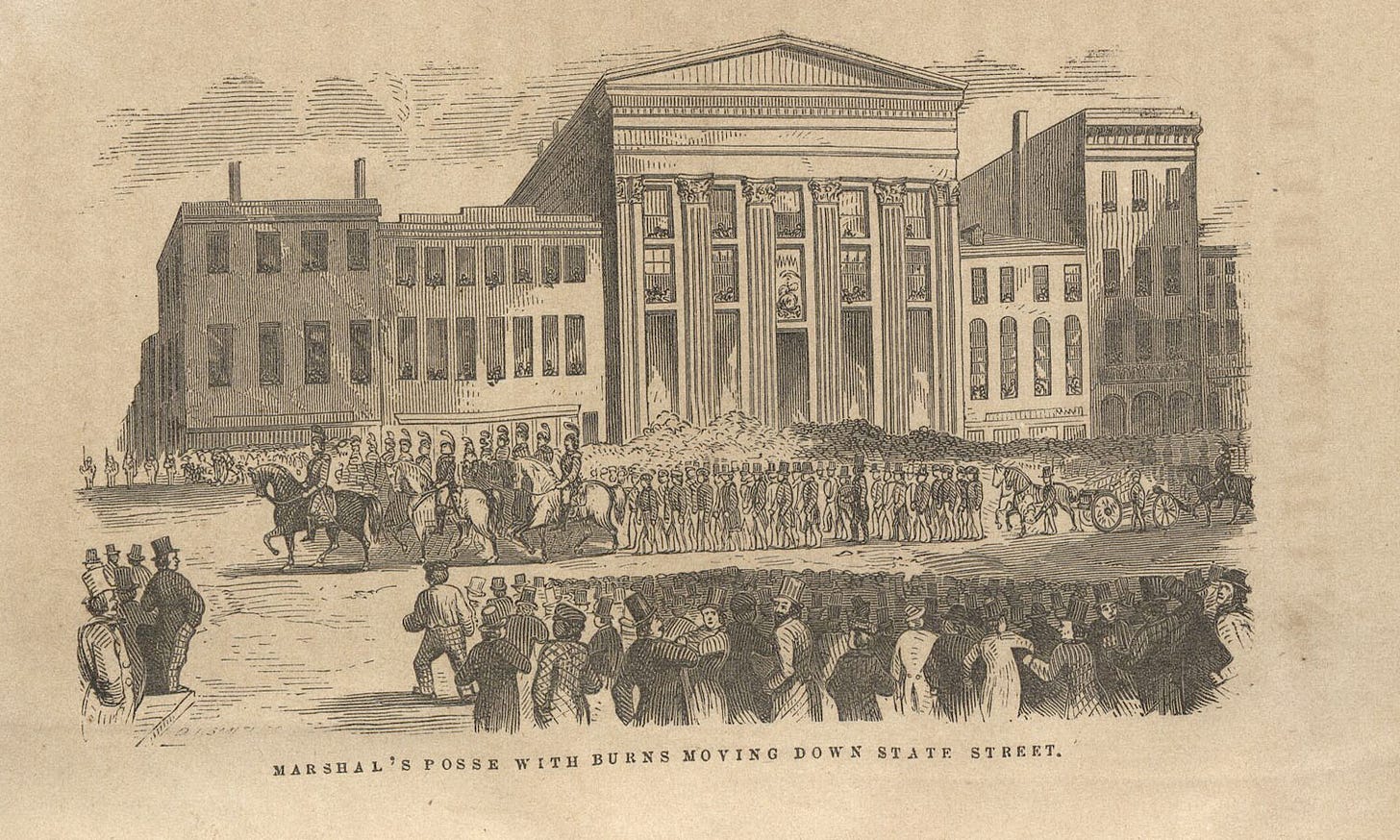

The most famous of these confrontations came in 1854, with the arrest of Anthony Burns in Boston. Federal troops marched Burns, in chains, through streets lined with 50,000 Bostonians to the harbor and a waiting ship back to Virginia. Buildings were draped in black, flags hung upside down.

For many who had clung to compromise, this was the breaking point. Amos Lawrence, a prominent conservative Whig, captured the moment: “We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs and woke up stark mad Abolitionists.” The spectacle had backfired.

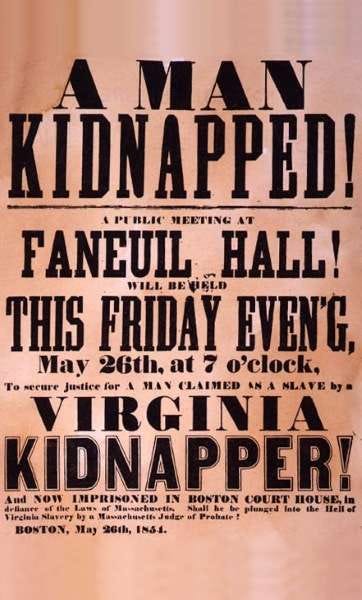

This was a media war as much as a political one. Abolitionist presses like William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator and Frederick Douglass’s North Star published eyewitness accounts, posters warning Black residents of slave catchers, and editorials framing each arrest as an assault on liberty itself. Pro-slavery papers depicted the rescuers as criminals, anarchists, rioters, and traitors.

Mainstream Northern papers often struck a middle tone, condemning both slavery and “mob rule,” though their positions shifted as public outrage grew. The information ecosystem was slow by today’s standards, but factionalism was already entrenched. Each side had its own facts, its own frame, and its own audience.

Trump’s interventions operate in a more chaotic media environment. In the hours after his D.C. announcement, his imagery — the martial backdrop, the language of crisis — dominated cable news and social media. His critics responded, but the first frame was his. The abolitionists understood the importance of speed: get the public in the street, get the pamphlets printed, before the official story hardens. Civil society today has the tools — livestreams, social platforms, independent outlets — but not always the coordination to seize the first frame or the scale of mobilizing a real public.

In the 1850s, the line between elected authority and civil resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act varied sharply from city to city, and that variation often determined the outcome. In Syracuse, New York, the mayor, Alfred H. Hovey, presided over public meetings denouncing the law and urging residents to oppose its enforcement. The city’s vigilance committee was openly backed by local leadership, creating an environment where federal marshals could not count on municipal cooperation. The county sheriff’s request to call out the militia was overruled. In effect, civil society was in the lead, but its power was magnified because local officials declined to intervene on behalf of the federal government. The result was a kind of unofficial sanctuary city, where the norms of the city and the law of Washington were in open conflict.

Boston told the opposite story. Its abolitionist movement was large and loud, but when Anthony Burns was seized in 1854, the city’s mayor and the state’s governor sided with federal authority. Mayor Jerome V. C. Smith called out the militia—not to block the rendition, but to reinforce it. Governor Emory Washburn, who personally described the law as “cruel and wicked,” still refused to use state power to interfere, insisting that his constitutional duty bound him to respect federal enforcement. Civil society still turned out in force, crowding the streets and courthouse, but it faced both federal and local government aligned against it. That alignment mattered: Burns was marched to the harbor under heavy guard and sent back to slavery. Yet the spectacle shifted politics. Within a year, Massachusetts had a new governor and a sweeping Personal Liberty Law designed to prevent any future rendition.

What the contrast suggests is that while the abolitionist movement’s speed, organization, and willingness to confront authority were decisive, sympathetic or at least non-cooperative local officials could turn an isolated act of defiance into a broader civic stand. In places like Syracuse, where elected leaders created political cover for resistance, the risk calculus for federal agents changed. In places like Boston, the absence of that cover made resistance costlier and more dangerous—but the same public confrontations could still shift the political ground, pushing reluctant officials toward a more oppositional stance. That dynamic between grassroots action and elected authority remains a central question in any confrontation with federal overreach: does civil society act alone, or does it find points of synergy with those in office who are willing to resist?

In 1854, the sight of a man in chains under armed guard transformed thousands of bystanders into committed abolitionists. The Burns case became a rallying cry, shifting public opinion and altering state policy. Today’s civil society may need to think in similarly catalytic terms: which images, which moments, will turn passive observers into active opponents of creeping authoritarianism? And how can those moments be seized, not just endured?

When the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, many in the North imagined they could live with it, that it was a price worth paying to preserve the Union. Four years later, after Jerry, Shadrach, Burns, and others, that calculation had changed. The federal show of force meant to intimidate had instead radicalized centrists and liberals into Republicans and abolitionists. In our own time, we should remember that even the most carefully staged assertion of power can be undone if the public sees clearly what is at stake and if civil society is ready to act before the narrative is set.

urgent action - give every person 'on the street' in D.C. a sign that says:

I AM NOT IN THE EPSTEIN FILES

John Galton

Thank you for this in depth report from history.

Distressing now is the ambivalence of so many Americans after almost two years of killing and destruction by Israel with full US government backing. Most Americans are so far removed from even the smallest deprivation that is no relating to those losing everything.

There is even broad support for the terrible situation of the illegal immigrants who are being hunted down and imprisoned. Have we forgotten the anti-slavery medallion that said "Am I Not a Man and a Brother"? America being in service to the 1% has to come to an end and that means from you and me, from the bottom up as it will never come from the top down.