Realignment Isn’t A Playlist

On Searchlight, why Democrats can’t simply curate their way to power and what it takes to forge an era of democratic renewal.

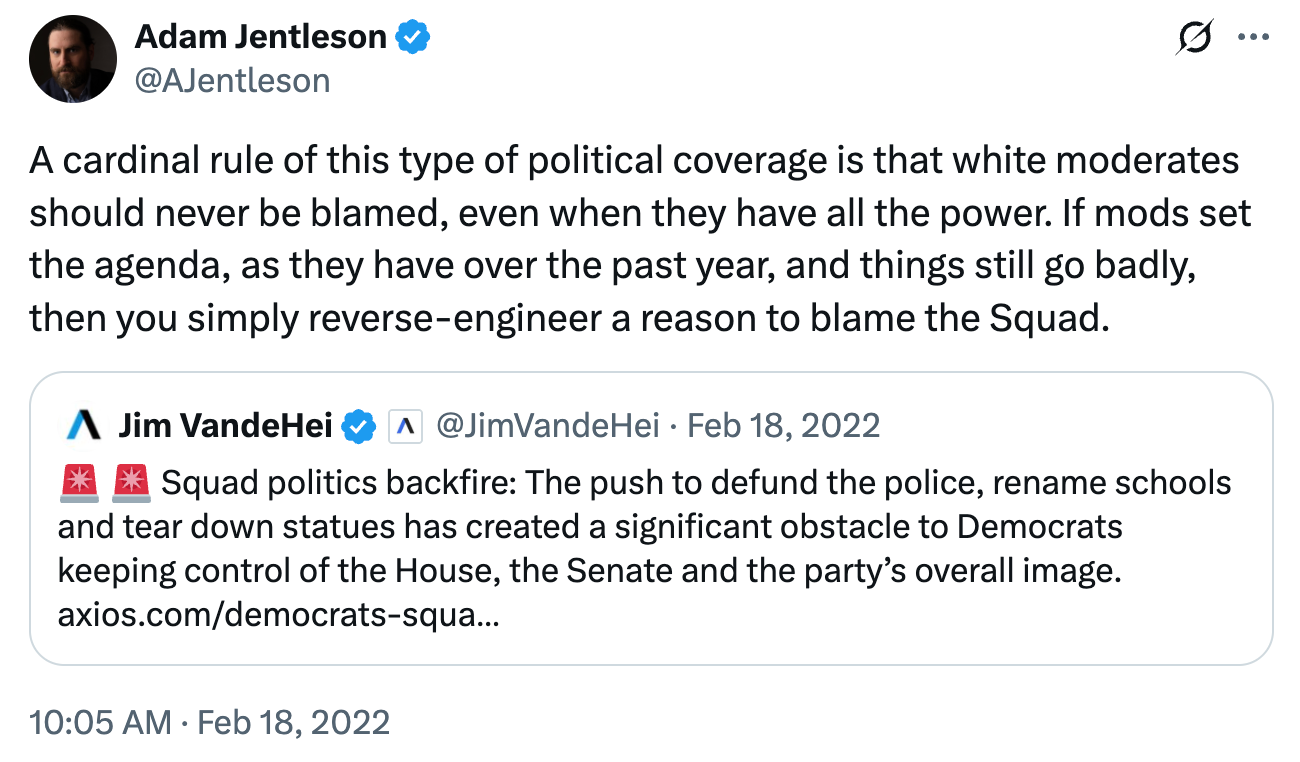

The pitch behind Adam Jentleson’s new Searchlight Institute is deceptively simple: American politics is stuck at 51–49, and the way out is a heterodox “supermajority” bundle—drop divisive planks, add cross-pressuring ideas. Searchlight is right that Democrats face a legitimacy crisis and shouldn’t be trapped by stale boxes. But it mistakes realignment for branding—compressing a social process built by movements, institutions, political economy, and organized power into an algorithmically curated playlist.

Realignment isn’t about clever curation to please in the moment. It’s the sound of factions and interests clashing, a noisy orchestra tuning through dissonance until, after hard rehearsal and bruising conflict, it can finally play in time. Realignment isn’t shuffling issues on a menu; it’s democracy testing its strength, renewing itself through organized struggle.

If that diagnosis sounds abstract, the scholarship gives it concrete shape: realignments aren’t about reshuffling issues on a menu; they decide who holds power and how it’s organized. Timothy Shenk shows they depend on brokers and coalition-builders who can translate movement energy into durable party coalitions. Daniel Schlozman shows they endure when social movements become “anchors” within parties—offering votes, money, and networks that parties need, and in return gaining influence over policy priorities and personnel. Stephen Skowronek argues that reconstructive leaders seize crisis moments to rebuild authority and remake institutions so a new regime reproduces itself. Corey Robin reminds us that these leaders define themselves by confronting entrenched regimes rather than triangulating within existing alignments. Taken together, their work shows realignments are forged as movements, parties, and leaders remake the architecture of American politics.

Measured against that standard, Searchlight’s own invocation of Schattschneider—“the definition of the alternatives is the supreme instrument of power”—lands short. It never names the regime its alternatives are meant to displace. In Robin’s telling, reconstructors define themselves against a ruling order—Lincoln versus the Slave Power, FDR versus the “economic royalists,” Reagan versus the liberal interest-group order—and then organize to break the institutions that sustain it. By contrast, Searchlight’s adversary looks less like a regime than a roster of progressive nonprofits—an intra-camp grievance, even as a Trump-led GOP targets many of those same civic organizations with Orbán-style tactics. If “defining the alternatives” is to be more than rebranding, it has to specify the oligarchic order to confront and the machinery for contesting it.

Searchlight’s own framework can’t quite hold together. Point two urges Democrats to “defy ideological boxes” and build a heterodox mix from first principles. Point three turns immediately to polling, insisting that leaders track where the public sits, even if opinion is “malleable.” The tension is never resolved. The underlying theory of realignment here is oddly bloodless: no sense of movements, institutions, or social forces, only the idea that the right combination of words in politicians’ mouths will shuffle the coalitional deck. That’s not how realignments have ever worked; it’s how ad campaigns work. It’s politics imagined as a television ad buy, not as a democratic struggle.

To be fair, some of Searchlight’s critique is real: parts of the progressive ecosystem have ossified into professionalized silos, as Jacobin’s criticism of the PMC has often declared, more accountable to funders and lists than to the people they claim to represent. But this isn’t just about “leftist activist groups.” As Sam Rosenfeld argues, today’s Democrats are a coalition of New Politics–era movements—feminism, environmentalism, Black and Latino civil rights, labor, consumer advocacy—now institutionalized inside the party (leaders like Jim Clyburn and the Congressional Black Caucus, UnidosUS, Randi Weingarten’s teachers’ unions, Planned Parenthood, EMILY’s List, LCV/NRDC, MoveOn, etc).

The challenge isn’t that these organizations lack legitimacy—they’re crucial power centers—but that, taken together, they leave gaps in everyday democratic practice. That gap helps explain why new efforts—Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Indivisible, DSA, Sunrise—have surged in the past decade, seeking to build participatory vehicles where legacy groups sometimes operate more as partisan mobilization arms for the Democratic Party. In an attention economy shaped by social-media silos, inequality, and atomized late capitalism, the task isn’t to abolish “the groups” but to re-root them in civil society: unions that organize, neighborhood associations that convene, tenants’ and parents’ groups that act.

These new forms of association won’t look like the past—an influencer or a Twitch stream can now mobilize more authentic participation than many legacy groups, and the next surge of collective action may look as unruly and unexpected as the GameStop squeeze. But whatever form it takes, we can’t cede democratic life to technocrats, pollsters, and consultants; politics endures only when people organize themselves into something larger than their own atomized lives. As Hannah Arendt wrote: “Political questions are far too serious to be left to the politicians.”

Seen historically, the difference between branding and realignment becomes clearer. Searchlight’s Social Security case study on their website, for example, shows how thin the analysis gets. It implies that groups to Roosevelt’s left would have rejected Social Security and that only FDR’s choice to target the elderly and rely on payroll taxes made the program possible. The record runs differently. The Townsend movement wasn’t the CIO’s labor-left; it was a populist surge of older and middle-class Americans that Washington couldn’t ignore.

As FDR’s Labor Secretary Frances Perkins recalled in her memoirs, “One hardly realizes nowadays how strong was the sentiment in favor of the Townsend Plan… The pressure from its advocates was intense. The President began telling people he was in favor of adding old-age insurance clauses to the bill and putting it through as one program.”

President Roosevelt himself admitted to Perkins, “We have to have [old age insurance]. The Congress can’t stand the pressure of the Townsend Plan unless we have a real old-age insurance system, nor can I face the country without having devised…a solid plan which will give some assurance to old people of systematic assistance upon retirement.”

This is precisely how bottom-up organizing gives democracy its force. As Edwin Amenta argues in When Movements Matter, the Townsend Plan shows movements shape outcomes less by winning maximal demands than by forcing action and creating space for feasible reforms: “The fledgling old-age insurance program…would not have been added…without the rapid mobilization behind the Townsend Plan.”

Meanwhile, the CIO and the labor-liberal left treated Social Security as a landmark, even as they criticized racist exclusions for farm and domestic workers and worked to expand coverage. Perkins recalled that Treasury Secretary Morgenthau insisted on omitting those groups, despite early agreement on universal coverage: “This was a blow…universal coverage had been agreed upon almost from the outset.” In practice, Townsend’s populists opened the window, left and labor critics refined the design, and the CIO’s institutional heft carried Social Security from precarious start to durable cornerstone—like an orchestra lurching into tune, dissonant sections converging on a shared score.

Which brings us to conflict. Searchlight’s website insists it is not afraid of it: “Rather than shy away from conflict, we must embrace it in good faith.” The test isn’t the line; it’s whether conflict is converted into institutions. Too often, elite coalition management waits out energy and trims hard issues to keep a tidy brand. But politics doesn’t work that way. The mistake in the “play down divisive issues” advice is assuming those fights can be avoided. What’s happened to Kilmar García and Mahmoud Khalil, or the treatment of Los Angeles residents and Brad Lander and Alex Padilla on immigration and ICE, isn’t background noise—it’s the raw material of politics. Realignment often requires the opposite of waiting out controversy: choose the ground, frame the fight so your bloc holds, deliver fast, legible wins, and build organizations that can withstand backlash.

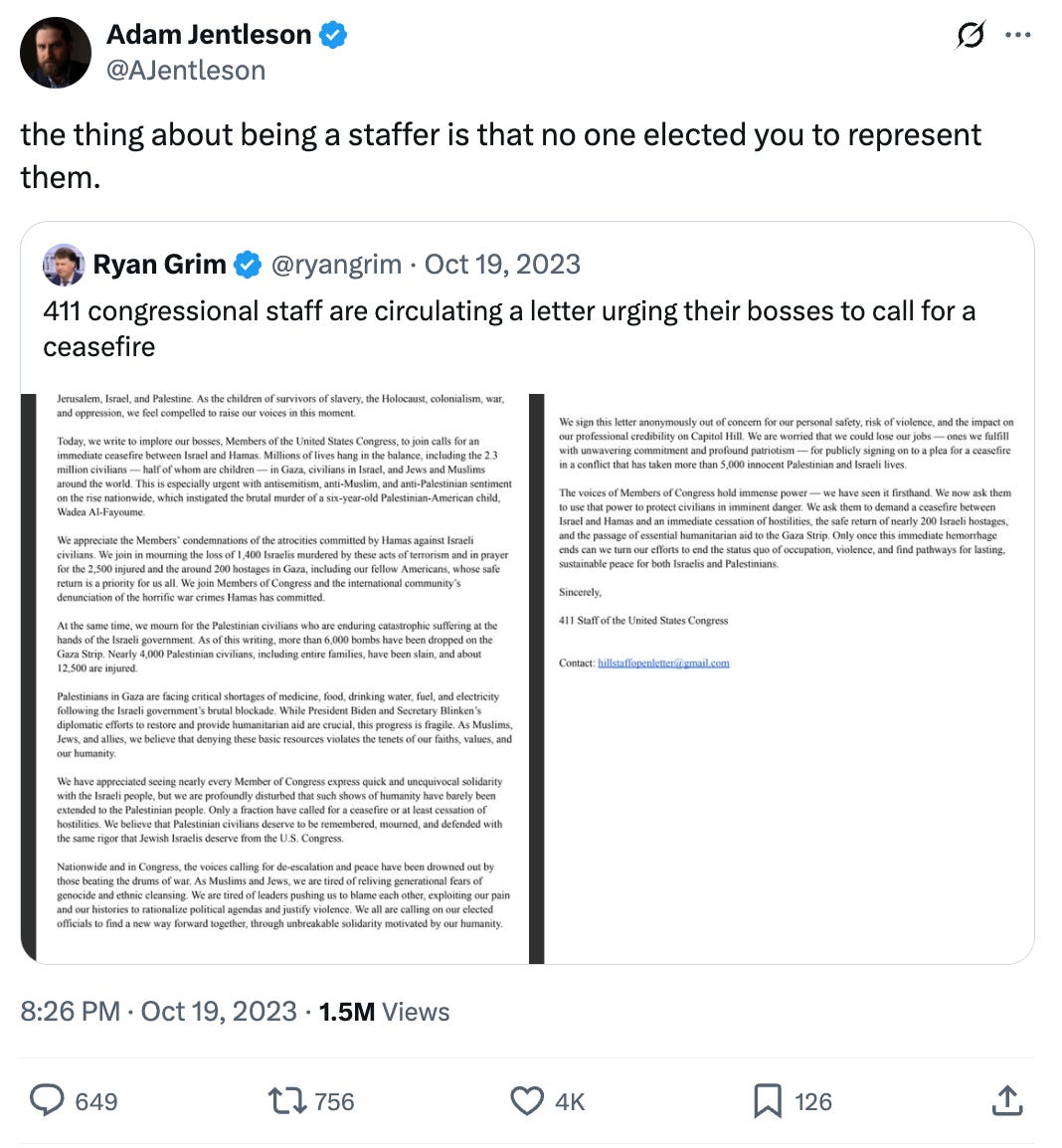

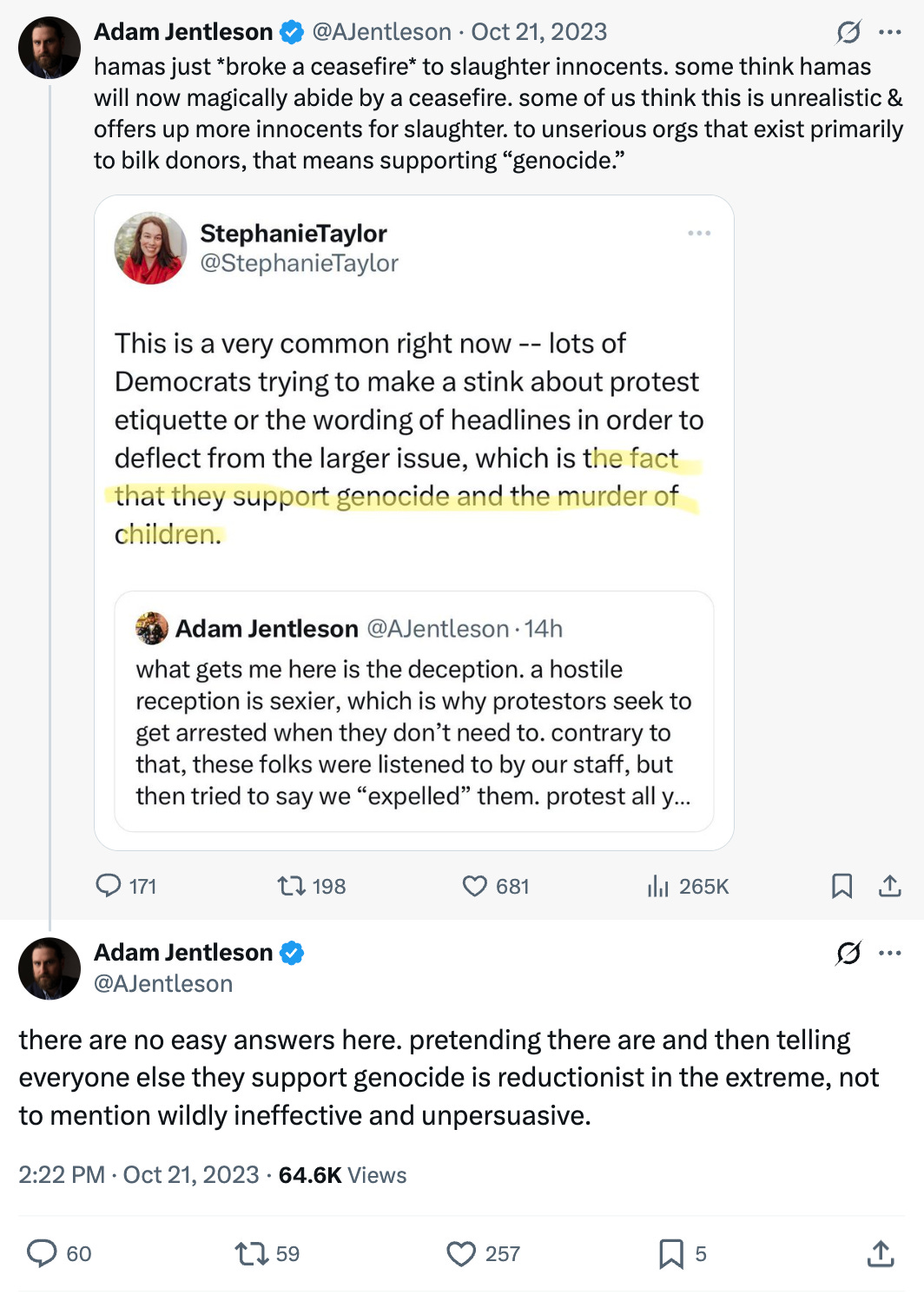

The record of Searchlight’s leadership tells another story. Many of the alumni of Fetterman’s office who now steer Searchlight spent 2023 and 2024 not merely avoiding conflict but working to contain it. They rolled their eyes at Democrats advocating for a ceasefire and weapons restrictions, dismissing them as unserious or ill-strategized, all while serving a boss who was the Senate’s loudest champion of Israel’s horrific war crimes. They offered cover for him, waving around polling to insist Fetterman’s violent positions on Israel made him more popular, sneering at dissent as unserious, childish Group-think, even as the bombing of Palestinian civilians worsened.

Conflict, for them, was not democracy’s lifeblood but an obstacle to be neutralized, a branding problem to be managed. And now, like so many Democrats, they stand apart from the wreckage, hands scrubbed clean—as though cover were not a choice, as though complicity were not a position—and still decline to take a substantive stand. As Ta-Nehisi Coates puts it, “If you can’t draw the line at genocide, you probably can’t draw the line at democracy.”

The same lesson applies to strategy and message. Politics has craft, but it isn’t only craft. Yes, smart operatives try to split the other side and avoid gratuitously fracturing their own coalition. But some fights are defining, and opinion moves when organized actors force it to move. In 2006, it made little sense to tell a New York Democrat to hide support for marriage equality; just as it was wrong to ask Muslims and liberals to accept Harry Reid’s opposition to the so-called “Ground Zero mosque.” The point is simple: if politics is only vibes and risk minimization and “hippie-punching,” nothing consequential ever changes about the dynamics of power.

Nor is this just theoretical. The same blind spot has led centrists, at various points over the past decade, to wave off proposals like Medicare for All, a $15 minimum wage, debt relief, rent freezes, breaking up Big Tech, or ending U.S. weapons aid to countries Israel and Saudi Arabia. They’re dismissed as unrealistic or too divisive—just as Townsend’s pensions were caricatured in the 1930s. But realignments don’t emerge from consensus; they move through conflict and the opening of space. Movements elevate demands at the margins, force parties to grapple with them, and through struggle reshape coalitions and institutions. Social Security, collective-bargaining rights, clean energy programs, civil-rights statutes—none were born as consensus policies. They became durable because agitation created pressure, parties absorbed it, and leaders rewrote the rules to embed it.

Sara Miles’s account of the 1990s shows what happens when Democrats try to short-circuit the realignment process with a donor-anchored, top-down refit. The “Atari Democrat” turn gave the party a fluent idiom of growth and innovation and a recognizable partnership with a rising industry in Silicon Valley. But the real shift was organizational. The New Democrat Network was built as a “mini-campaign operation” to assemble a congressional bloc and keep a New Democrat White House from backsliding toward labor-aligned priorities. Silicon Valley intermediaries professionalized access and signaling; high-profile policy flips and choreographed endorsements announced who had the inside line.

That history matters because it names the model Searchlight is at risk of reviving. It changed who Democrats listened to and built a D.C. apparatus to enforce that change, while bypassing the democratic anchoring and rule-rewiring that make eras durable. Think of the distinction this way: patron networks replaced mass membership organizations, and neoliberals displaced strategies to overcome veto points that root new policies in constituencies able to defend them. Searchlight’s “supermajority thinking”—heterodox bundles, cleaner polling, hostility to “the groups”—is at risk of a similar operating system with a new interface. It’s elite coalition management: good at message control and donor reassurance, thin where it counts—turning conflict into organization, organization into policy, and policy into a regime that can endure.

It is, of course, too early to know what the Searchlight Institute will ultimately become. We may actually agree more than we disagree. But the test of democratic institutions requires the organization of ordinary Americans into forms capable of exercising power. On that score, given the record, it is not yet clear whether Searchlight will strengthen or weaken the conditions that sustain a just democracy.

If you want a contrast between curation and coalition-building, look at Harry Reid’s 2010 gamble on the DREAM Act. The polling was bad and his advisers said to steer clear. DREAMers protested his office anyway, and Reid chose to stand with them. That choice worked because democracy’s three legs were there: organized people who could make claims and be seen; skilled staff who could turn those claims into a legislative path; and a leader willing to take a public risk and be accountable for it. The strength of the groups mattered—they created a mandate no memo could invent. Without them, operatives have no charge and politicians no obligation. Given a real stake and a real reason, Latino voters showed up and rewarded him. That is what a realignment instinct looks like: strong organizations that hold leaders to account, operatives who channel that pressure into strategy, and a courageous politician who answers with action.

It is also hard to take seriously the idea that “the groups” cost Harris the 2024 election, when the overwhelming liabilities were inflation, Biden’s age, and a White House inner circle that often sneered at dissent (not to mention that Searchlight-adjacent thinkers like Matt Yglesias and David Shor had the ears of Democratic Party leaders). Still, in a two-party system, there will always be groups organizing constituencies to have their needs met across a range of issues; that is not a pathology but the basic structure of democratic politics. The task is not to ride the vibe-shift and wish groups away but to build better ones, bring them into greater synchronicity, and accept that conflict will always exist. How leaders navigate that conflict is what makes realignments possible.

But realignment likely won’t be born in conference rooms where operatives draft memos about “supermajorities.” It will be found where people already wrestle with the hard edge of American life: where immigrants and their allies stand against ICE raids, where Indivisible moms organize neighbors, where Palestinian and Lebanese families in Michigan grieve their dead, where tenants fight rent hikes, where women defend their health care, where the indebted refuse their burdens, where families demand release from mandatory minimums, where young people fight for a livable planet and social media platforms that serve us, where workers organize unions against the odds. These are the places where power lives.

Leaders untethered from many of these struggles, like John Fetterman, may win in the short-term, but they can’t deliver realignment. Even with imperfect groups, the further we drift from these fights, the further we drift from power.

DUMP AND IMPEACH TRAITOR , NAZIS , FELONS, PREDATORS ,AND CON REPUBLICONS EVERYWHERE. YES CON REPUBLICONS, CLIMATE CHANGE IS DANGEROUS, REAL, DISRUPTIVE WORLDWIDE, COSTLY, AND PREVENTABLE. STOP DENYING CLIMATE CHANGE AND FACE THE SCIENCE . DUMP THE CON RTRUMP AND CRONIES. DEPORT RTRUMP'S WIFE AND RELATIVES. BOYCOTT NAZI MUSK AND NAZI RTRUMP. VOTE FOR DEMOCRACY AND THE FAIR DEAL, NOT THE RAW DEAL.

Charlie Schumer has been around a long time and so have I. There’s nothing Searchlight has to say that I haven’t heard a thousand times already. MAGA lite. Zzzzzz.